BAN THE BOMB

Nuclear Weapons and the Cold War

By Karl Meyer - July 2020

In the two decades from 1945-1965, the end of World War II until escalation of the Vietnam War, peace movements in the United States were rather small. Our biggest concern was the rapid development, proliferation, and atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, and the serious threat of catastrophic nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The main peace movement tendencies were expressed in the moderate educational and political lobbying programs of the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), the religious pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), and the radical secular pacifist War Resisters League (WRL) and thePeacemakers movement.

I was active with WRL and Peacemakers., starting in 1957 when I was twenty years old. In 1957 radical pacifists from WRL, Peacemakers, and Quaker groups came together to form the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA).

CNVA began to organize a series of annual nonviolent direct action projects challenging the legal boundaries of nuclear weapons development and testing sites. We called it "civil disobedience". Governments called it "trespassing". We have come to believe that the governments were breaking international and Constitutional law, and we were legally asserting the Constitutional rights of free speech and peaceable assembly promised in the First Amendment.

In 1957, '58 and '59, I joined Ammon Hennacy, Dorothy Day, and a few other Catholic Workers and supporters in defying mandatory statewide air raid drills in New York, ostensibly intended to train people to protect themselves by sheltering in buildings in case of a massive Soviet nuclear attack on the United States. We sat outside on park benches near the Catholic Worker house in lower Manhattan, while we were supposed to be hiding in buildings and basements. We were arrested and sentenced to jail for thirty days in 1957, thirty days (suspended) in 1958, and fifteen days in 1959.

In 1957, still a "juvenile" at age twenty under New York law, I did my time alone at the still notorious Rikers Island snake pit prison. I came out unscathed, and having earned respect at the Catholic Worker, in peace movements generally, and from my Barnes and Noble employers.

Small CNVA teams "trespassed" into restricted nuclear testing and development zones in Nevada (1957) and the central Pacific Ocean and Wyoming (1958). Participants were arrested, tried, and sentenced to modest terms of prison or probation.

In 1959, Bradford Lyttle and A.J. Muste, sponsored by CNVA, organized an "Omaha Action" project for similar protests at an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) silo site being built at Mead, Nebraska, near Omaha.

Up to that time the chosen vehicle for delivering nuclear bombs at prospective Soviet targets had been long-range bomber planes that would take many hours in flight to reach their targets, and were quite vulnerable to being shot down by air raid defense batteries or fighter planes along the way.

The military's solution was ICBM rockets launched rapidly on warning, from highly fortified underground silos in the midwestern plains. They could reach their targets in less than a half hour, and were almost invulnerable to being shot down on the way. One of the first of these Atlas missile silos was being built at Mead in the summer of 1959.

I joined the project team in June. A.J. and Ross Anderson, both elderly Protestant ministers, and I were chosen to be the first of several small teams that would enter the site over a period of several weeks, to extend attention to the educational goals of the project. At that time, arrest and imprisonment for protest actions was far less frequent than at present, and could gain national, and even worldwide, attention.

We crossed the fence at the site on July 1. We were arrested immediately and arraigned in federal court the next day. We spent a week in jail, and on July 9, Judge Richard Robinson sentenced us to six months each in prison and a $500 fine. He then suspended the sentence and put us on probation for one year, with the special condition that we stay away from protest actions at military bases anywhere in the United States for the whole year.

"I'm handing you the key to the jail," he said. I told him then and there that I would not likely obey that condition, but he overrode my objection.

I returned to the base with the second team two days later, was promptly arrested and returned to court, where Robinson imposed the promised prison sentence. I did my time at federal prison camps in Springfield, Missouri, and Allenwood, Pennsylvania. (Though it remains due for the rest of my life, I have never paid the $500 fine, in spite of numerous visits from FBI agents in the early years, to see if they could persuade me to pay.)

By the conclusion of Omaha Action, fifteen of us had been arrested; seven were sent to jail for six months for crossing the fence and returning in violation of probation; six complied with the probation terms; Erica Enzer and John White did brief terms in a local jail for sitting in a roadway to block truck traffic into the site. This is how seriously we felt about the nuclear threat to humanity in Earth.

The main peace movement tendencies were expressed in the moderate educational and political lobbying programs of the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), the religious pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), and the radical secular pacifist War Resisters League (WRL) and thePeacemakers movement.

I was active with WRL and Peacemakers., starting in 1957 when I was twenty years old. In 1957 radical pacifists from WRL, Peacemakers, and Quaker groups came together to form the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA).

CNVA began to organize a series of annual nonviolent direct action projects challenging the legal boundaries of nuclear weapons development and testing sites. We called it "civil disobedience". Governments called it "trespassing". We have come to believe that the governments were breaking international and Constitutional law, and we were legally asserting the Constitutional rights of free speech and peaceable assembly promised in the First Amendment.

In 1957, '58 and '59, I joined Ammon Hennacy, Dorothy Day, and a few other Catholic Workers and supporters in defying mandatory statewide air raid drills in New York, ostensibly intended to train people to protect themselves by sheltering in buildings in case of a massive Soviet nuclear attack on the United States. We sat outside on park benches near the Catholic Worker house in lower Manhattan, while we were supposed to be hiding in buildings and basements. We were arrested and sentenced to jail for thirty days in 1957, thirty days (suspended) in 1958, and fifteen days in 1959.

In 1957, still a "juvenile" at age twenty under New York law, I did my time alone at the still notorious Rikers Island snake pit prison. I came out unscathed, and having earned respect at the Catholic Worker, in peace movements generally, and from my Barnes and Noble employers.

Small CNVA teams "trespassed" into restricted nuclear testing and development zones in Nevada (1957) and the central Pacific Ocean and Wyoming (1958). Participants were arrested, tried, and sentenced to modest terms of prison or probation.

In 1959, Bradford Lyttle and A.J. Muste, sponsored by CNVA, organized an "Omaha Action" project for similar protests at an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) silo site being built at Mead, Nebraska, near Omaha.

Up to that time the chosen vehicle for delivering nuclear bombs at prospective Soviet targets had been long-range bomber planes that would take many hours in flight to reach their targets, and were quite vulnerable to being shot down by air raid defense batteries or fighter planes along the way.

The military's solution was ICBM rockets launched rapidly on warning, from highly fortified underground silos in the midwestern plains. They could reach their targets in less than a half hour, and were almost invulnerable to being shot down on the way. One of the first of these Atlas missile silos was being built at Mead in the summer of 1959.

I joined the project team in June. A.J. and Ross Anderson, both elderly Protestant ministers, and I were chosen to be the first of several small teams that would enter the site over a period of several weeks, to extend attention to the educational goals of the project. At that time, arrest and imprisonment for protest actions was far less frequent than at present, and could gain national, and even worldwide, attention.

We crossed the fence at the site on July 1. We were arrested immediately and arraigned in federal court the next day. We spent a week in jail, and on July 9, Judge Richard Robinson sentenced us to six months each in prison and a $500 fine. He then suspended the sentence and put us on probation for one year, with the special condition that we stay away from protest actions at military bases anywhere in the United States for the whole year.

"I'm handing you the key to the jail," he said. I told him then and there that I would not likely obey that condition, but he overrode my objection.

I returned to the base with the second team two days later, was promptly arrested and returned to court, where Robinson imposed the promised prison sentence. I did my time at federal prison camps in Springfield, Missouri, and Allenwood, Pennsylvania. (Though it remains due for the rest of my life, I have never paid the $500 fine, in spite of numerous visits from FBI agents in the early years, to see if they could persuade me to pay.)

By the conclusion of Omaha Action, fifteen of us had been arrested; seven were sent to jail for six months for crossing the fence and returning in violation of probation; six complied with the probation terms; Erica Enzer and John White did brief terms in a local jail for sitting in a roadway to block truck traffic into the site. This is how seriously we felt about the nuclear threat to humanity in Earth.

The Nonviolent Movement &

The American Peace Movement

(This is a selection from among "Easy Essays" that I wrote from jails and prisons in 1959 and 1960.)

Douglas County Jail

Omaha, Nebraska

July, 1959

I - Words and Facts

In Bread and Wine

Ignazio Silone says

that the peasants Italy

did not submit

to the propaganda

of Mussolini.

They submitted

to the fact of his power.

And they would not respond

to the counter-propaganda

of the revolutionists,

but they might respond to revolutionary facts.

Peter Maurin said

that a leader has only

to shout a word.

Silone says

that the leader had only

to present a fact.

Peter Maurin said

that discipline was Mussolini’s word.

Silone says

that discipline

was Mussolini’s fact.

I believe

that the liberals,

and the students,

and the intellectuals of America

do not submit

to the propaganda of the military.

I believe

that they do submit

to the fact

that the nation

is committed to war

overwhelmingly.

And I believe

that they will not respond

to the counter-propaganda

of the pacifist movement

but they might respond

to the fact

of a nonviolent revolution

against war.

Medical Center for Federal Prisoners

Springfield, Missouri

July, 1959

Taking us to

Springfield Federal Prison,

Marshal Raab taught us this maxim:

If you can’t do time

don’t commit crime.

Some pacifists say,

“If we do time

we won’t have time

to start a revolution.”

Catholic Workers say,

“If you can’t do time

don’t start a revolution.”

In The Mystery of the Charity of Joan of Arc,

Charles Peguy says that

we must return to God together.

We cannot abandon our brothers

and then return to God alone.

We must live together

or we will die together.

In our time

to live will be a revolution.

John Mower's Life Points a Stir Wise Moral for the Peace Movement

(John was a friend and frequent guest at my shelter for homeless men, a petty conman, who had served time in many jails and prisons as a consequence of his vocation.)

Prisons set up to deter

small wrongs

against good laws

have also deterred

just resistance

against bad laws.

All petty crimes of larceny

against the sacred petty bourgeois

rights of property

are weighed as nothing to

the crime of those

who fight the war

and those

who pay for it

and also those

who just omit

the sacred duty

of resistance.

Charles Peguy said,

Accomplice, accomplice, is

altogether the same as

author.

He who commits

a crime

has at least the courage to commit it;

But he who permits

a crime to be committed

is just as guilty as

he who commits it

and is a coward

to boot.

Douglas County Jail

Omaha, Nebraska

July, 1959

I - Words and Facts

In Bread and Wine

Ignazio Silone says

that the peasants Italy

did not submit

to the propaganda

of Mussolini.

They submitted

to the fact of his power.

And they would not respond

to the counter-propaganda

of the revolutionists,

but they might respond to revolutionary facts.

Peter Maurin said

that a leader has only

to shout a word.

Silone says

that the leader had only

to present a fact.

Peter Maurin said

that discipline was Mussolini’s word.

Silone says

that discipline

was Mussolini’s fact.

I believe

that the liberals,

and the students,

and the intellectuals of America

do not submit

to the propaganda of the military.

I believe

that they do submit

to the fact

that the nation

is committed to war

overwhelmingly.

And I believe

that they will not respond

to the counter-propaganda

of the pacifist movement

but they might respond

to the fact

of a nonviolent revolution

against war.

Medical Center for Federal Prisoners

Springfield, Missouri

July, 1959

Taking us to

Springfield Federal Prison,

Marshal Raab taught us this maxim:

If you can’t do time

don’t commit crime.

Some pacifists say,

“If we do time

we won’t have time

to start a revolution.”

Catholic Workers say,

“If you can’t do time

don’t start a revolution.”

In The Mystery of the Charity of Joan of Arc,

Charles Peguy says that

we must return to God together.

We cannot abandon our brothers

and then return to God alone.

We must live together

or we will die together.

In our time

to live will be a revolution.

John Mower's Life Points a Stir Wise Moral for the Peace Movement

(John was a friend and frequent guest at my shelter for homeless men, a petty conman, who had served time in many jails and prisons as a consequence of his vocation.)

Prisons set up to deter

small wrongs

against good laws

have also deterred

just resistance

against bad laws.

All petty crimes of larceny

against the sacred petty bourgeois

rights of property

are weighed as nothing to

the crime of those

who fight the war

and those

who pay for it

and also those

who just omit

the sacred duty

of resistance.

Charles Peguy said,

Accomplice, accomplice, is

altogether the same as

author.

He who commits

a crime

has at least the courage to commit it;

But he who permits

a crime to be committed

is just as guilty as

he who commits it

and is a coward

to boot.

SAN FRANCISCO TO MOSCOW WALK FOR PEACE (1961)

In 1960, Brad Lyttle and his CNVA colleagues conceived plans for two nonviolent action projects, Polaris Action and a cross-continental walk from San Francisco to Moscow to advocate for abolition of nuclear weapons, complete international disarmament, and personal refusal to submit to military conscription, to pay taxes for military purposes, or to work in military industries.

The U.S. Navy wanted a piece of the nuclear weapons budget pie. By 1960 they had gained approval for a Polaris Submarine program for shorter range missiles that could be launched from submarines invulnerably positioned deep in the oceans around the perimeters of the Soviet Union.

The first submarines were built at a shipyard in New London, Connecticut. CNVA organized a project for protesters to approach these vessels as they were being "Christened" and launched in the harbor at New London, and try to board them from canoes and small boats. CNVA activists carried out these plans in the summer of 1960, and established a long-term presence in New London with creation of a New England chapter of CNVA.

The San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace began on December 1, 1960 with a team of eleven walkers, often joined by local walkers along the way. They walked all the way through southwestern and mid-western states that winter. I joined as a team member as the Walk left Chicago on April 3, 1961, headed toward Washington, Philadelphia and New York.

Fifteen American team members were chosen by CNVA for continuing the Walk in Europe; fifteen European team members from five countries joined us in Europe, along with thousands of local walkers in cities and towns across Europe. After walking south from London, and boarding a ship in Southampton, we were barred from landing at Le Havre, France. We jumped overboard and swam to the dock. French police captured us. Four of us spent three days in an ancient jail waiting for the next ship out, after the police were not able to carry all of us back onto the Normania before it pulled away from the pier that night.

We continued the Walk through England, Belgium, West Germany and East Germany, arriving at a northern suburb of East Berlin on the very day before the Soviet Warsaw Pact powers announced closure of the border between East and West Berlin, in preparation for later building the Berlin Wall. That night we refused to interrupt the continuous Walk and take East German buses to the Polish frontier, to continue into Poland and Russia. Police carried us onto a bus, and expelled us into West Germany at Helmstedt.

Returning to Berlin across the access corridor, A.J. Muste, Brad Lyttle and I spent the first week of the most intense international crisis since World War II negotiating for transit visas across East Germany to continue the Walk in Poland and Russia. We were able to continue across Poland and Russia as far as Moscow, attracting huge local and international attention. We arrived in Moscow on October 3.

I sought permission to remain as a worker in Russia, hoping to learn Russian and be able to spend time alternately in the Soviet Union and the U.S. to educate and to promote international reconciliation and peace. I was turned down by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (the Soviet parliament).

The Walk was a great step forward in the developing process of dialog with the Soviet people and government in what became known as a "thaw" in the Cold War during the Khrushchev period. It was the first time Americans and West Europeans who did not support Soviet policies were allowed to enter the Soviet Union and discuss divergent political ideas so openly and widely.in public arenas.

In 1963 President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev negotiated a treaty to end atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, that had spread deadly nuclear radiation around the world for two decades. In later years other U.S. Presidents and Soviet leaders negotiated other agreements to limit the total numbers and the proliferation of nuclear weapons around the world, but the ultimate dangers from possessing and potentially using these weapons still hang over the world.

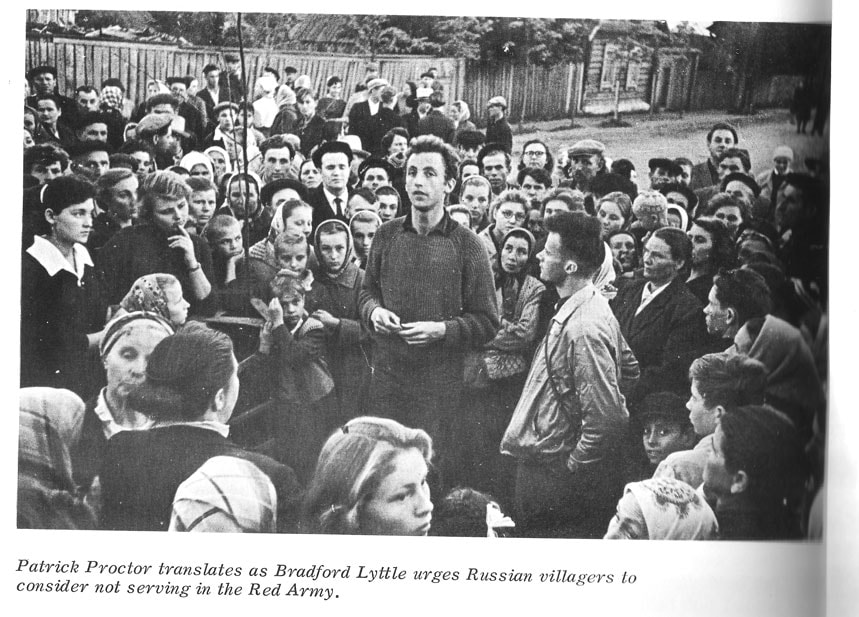

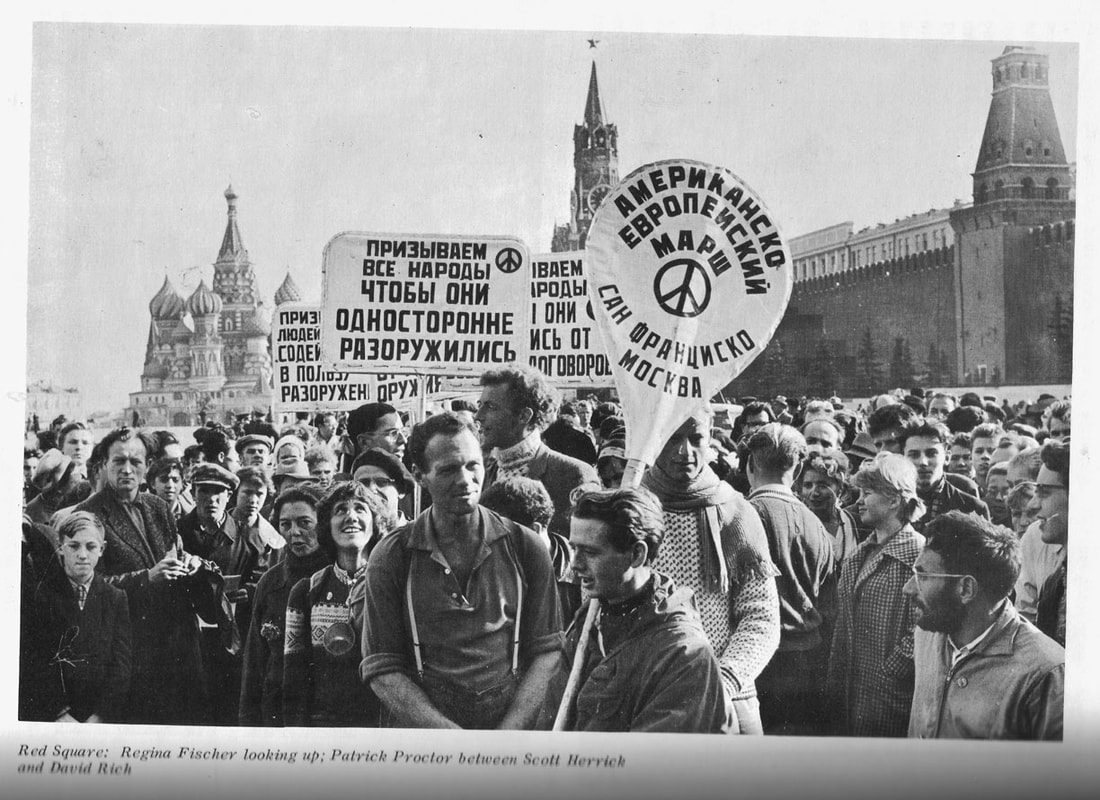

Two photographs below show Walkers talking to a typical gathering in a Russian village en route, and arriving in Red Square outside the Kremlin on October 3, 1961. Still Virgin Soil is a talk I gave at a large meeting to welcome us in New York on our return. It is reprinted in Seeds of Liberation, (1964, George Braziller) an anthology of writings from Liberation magazine.

Comprehensive accounts of the Walk are told in Bradford Lyttle's You Come With Naked Hands, (1966, Greenleaf Books), and in my autobiography, Positively Dazzling Realism.

The U.S. Navy wanted a piece of the nuclear weapons budget pie. By 1960 they had gained approval for a Polaris Submarine program for shorter range missiles that could be launched from submarines invulnerably positioned deep in the oceans around the perimeters of the Soviet Union.

The first submarines were built at a shipyard in New London, Connecticut. CNVA organized a project for protesters to approach these vessels as they were being "Christened" and launched in the harbor at New London, and try to board them from canoes and small boats. CNVA activists carried out these plans in the summer of 1960, and established a long-term presence in New London with creation of a New England chapter of CNVA.

The San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace began on December 1, 1960 with a team of eleven walkers, often joined by local walkers along the way. They walked all the way through southwestern and mid-western states that winter. I joined as a team member as the Walk left Chicago on April 3, 1961, headed toward Washington, Philadelphia and New York.

Fifteen American team members were chosen by CNVA for continuing the Walk in Europe; fifteen European team members from five countries joined us in Europe, along with thousands of local walkers in cities and towns across Europe. After walking south from London, and boarding a ship in Southampton, we were barred from landing at Le Havre, France. We jumped overboard and swam to the dock. French police captured us. Four of us spent three days in an ancient jail waiting for the next ship out, after the police were not able to carry all of us back onto the Normania before it pulled away from the pier that night.

We continued the Walk through England, Belgium, West Germany and East Germany, arriving at a northern suburb of East Berlin on the very day before the Soviet Warsaw Pact powers announced closure of the border between East and West Berlin, in preparation for later building the Berlin Wall. That night we refused to interrupt the continuous Walk and take East German buses to the Polish frontier, to continue into Poland and Russia. Police carried us onto a bus, and expelled us into West Germany at Helmstedt.

Returning to Berlin across the access corridor, A.J. Muste, Brad Lyttle and I spent the first week of the most intense international crisis since World War II negotiating for transit visas across East Germany to continue the Walk in Poland and Russia. We were able to continue across Poland and Russia as far as Moscow, attracting huge local and international attention. We arrived in Moscow on October 3.

I sought permission to remain as a worker in Russia, hoping to learn Russian and be able to spend time alternately in the Soviet Union and the U.S. to educate and to promote international reconciliation and peace. I was turned down by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (the Soviet parliament).

The Walk was a great step forward in the developing process of dialog with the Soviet people and government in what became known as a "thaw" in the Cold War during the Khrushchev period. It was the first time Americans and West Europeans who did not support Soviet policies were allowed to enter the Soviet Union and discuss divergent political ideas so openly and widely.in public arenas.

In 1963 President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev negotiated a treaty to end atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, that had spread deadly nuclear radiation around the world for two decades. In later years other U.S. Presidents and Soviet leaders negotiated other agreements to limit the total numbers and the proliferation of nuclear weapons around the world, but the ultimate dangers from possessing and potentially using these weapons still hang over the world.

Two photographs below show Walkers talking to a typical gathering in a Russian village en route, and arriving in Red Square outside the Kremlin on October 3, 1961. Still Virgin Soil is a talk I gave at a large meeting to welcome us in New York on our return. It is reprinted in Seeds of Liberation, (1964, George Braziller) an anthology of writings from Liberation magazine.

Comprehensive accounts of the Walk are told in Bradford Lyttle's You Come With Naked Hands, (1966, Greenleaf Books), and in my autobiography, Positively Dazzling Realism.

Still Virgin Soil

From Liberation Vol. VI, No. 9

[Date ungiven, estimated 1961?)

Following is the text of a talk given at Community Church in New York City at a packed meeting to welcome the Walkers on their return from Moscow.

Before I being, I want to say hello to an old man in the audience, and believe me, I am not doing it for his sake. I am doing it for your sakes, because I want to have a decent excuse for telling you something about his life. I am speaking of Max Sandin of Cleveland.

He is in his seventies. He was born in Russia, and may Russia send us thousands more like him. He came to America in his youth. During World War I, he was sentenced to be shot for refusing to wear the uniform or to fight in the War. His sentence was commuted, but he spent several years in Leavenworth prison under the terrible conditions that prevailed there during the War.

He hasn’t ever given up his work for peace. He keeps right no going. He doesn’t believe in paying taxes for way, and he doesn’t pay them, and that is something unusual. Recently the government took away his Social Security to pay the taxes he hadn’t paid. He went down to Washington to make a protest, and they tried to shut him up in a mental institution. He is here tonight, and we are honored by his being here.

Now let me say what I think I have to say about this Walk from San Francisco to Moscow:

“Tovarish, Sovietski Soyuse, Sovietski Narod, Sovietski Pravietyeltstva—Comrades, the Soviet Union, the Soviet People, the Soviet Government, desires peace; it needs peace; it demands peace. Myr, Myr, Myr—Peace, Peace, Peace. The Soviet Union, the Soviet People, the Soviet Government, needs peace so urgently that it is ready to resort to nuclear weapons, if necessary, to defend the peace to nuclear weapons, if necessary, to defend the peace against fascist aggression. And we can lick the man who says it isn’t so.”

Friends, I hope you won’t find this amusing, because I believe it is an accurate paraphrase of the words I heard in the Soviet Union—again, and again, and again. Words that I heard without a sound of dissent, except that one voice, which was not a sound, but rather a secret note passed to Bradford Lyttle at the Moscow University meeting, while the words I have just paraphrased were ringing through the hall—a secret note which read in full:

My dear friends, do not believe absolutely this dirty official and his common demagogic phrases. Go you path, we are with you.

When I remember these words—the shouted words and the silent words—it makes me angry to hear people in our peace movement gloating and saying, “For years we have been told to go tell it to the Russians, and now we can say we have gone and have ‘told it to the Russians.’”

I am not going to lie to you.

I hope that you will not say that I have been to the Soviet Union.

I hope that you will not say that you have been there.

I hope you will not say that our ideas have been presented there.

The fact is that we have not touched the Soviet Union.

We flicked in and out of the Soviet Union so fast that we hardly knew we were there. Our hosts had us so tied up in knots we had to roll along the ground from Brest to Moscow.

Hear a parable of the sower and the seed: A sower went out to sow, and as he sowed, some of the seed fell by the roadside, and the birds of the air devoured it as soon as it fell. Other seed fell on shallow, rocky ground, and it sprang up quickly, but it had no roots.

When the drought came, it withered and died. And finally other seed fell on good ground, and when it had taken root it grew and yielded fruit a hundredfold.

Now hear an explanation of this parable: The seed that fell by the roadside and was devoured by birds is those eighty thousand leaflets we distributed and those talks to villagers along the roadside.

We sowed the wind, and we reaped the wind. The seed that fell among briars is those public meetings you heard about where the party liners sprang to their feet and strangled our message with a barrage of words almost before we had finished speaking.

The seed that fell on shallow rocky soil is that meeting at the Moscow University, where the students heard our message so eagerly and yet had not the courage to speak out a word of dissent from official policy, even when we were there, but had to pass up their dissent in secret notes.

How will they grow when the water leaves them? As for the seed that fell on good ground, I do not know that it was ever sown. We haven’t touched the Soviet Union with our ideas. Perhaps not much more than Richard Nixon touched it in his famous kitchen debate. The Soviet Union is still virgin soil. Before you can sow the good soil, you have to plow the ground. And I mean plow the ground. And once having set your hand to the plow you must not turn back.

I have told you that we haven’t touched the Soviet Union yet. And how could we hope to touch them when we haven’t touched ourselves yet? How could we hope to reach them with our message, when we haven’t even reached our own souls through the fat layers of our American existence?

If we want to reach them, we have to go and reach them.

If we want to speak with them, we have to go and speak with them.

And if we want to live in peace with them, we have to go and live in peace with them, personally disarmed, in labor and in poverty, again, and again, and again!

[Date ungiven, estimated 1961?)

Following is the text of a talk given at Community Church in New York City at a packed meeting to welcome the Walkers on their return from Moscow.

Before I being, I want to say hello to an old man in the audience, and believe me, I am not doing it for his sake. I am doing it for your sakes, because I want to have a decent excuse for telling you something about his life. I am speaking of Max Sandin of Cleveland.

He is in his seventies. He was born in Russia, and may Russia send us thousands more like him. He came to America in his youth. During World War I, he was sentenced to be shot for refusing to wear the uniform or to fight in the War. His sentence was commuted, but he spent several years in Leavenworth prison under the terrible conditions that prevailed there during the War.

He hasn’t ever given up his work for peace. He keeps right no going. He doesn’t believe in paying taxes for way, and he doesn’t pay them, and that is something unusual. Recently the government took away his Social Security to pay the taxes he hadn’t paid. He went down to Washington to make a protest, and they tried to shut him up in a mental institution. He is here tonight, and we are honored by his being here.

Now let me say what I think I have to say about this Walk from San Francisco to Moscow:

“Tovarish, Sovietski Soyuse, Sovietski Narod, Sovietski Pravietyeltstva—Comrades, the Soviet Union, the Soviet People, the Soviet Government, desires peace; it needs peace; it demands peace. Myr, Myr, Myr—Peace, Peace, Peace. The Soviet Union, the Soviet People, the Soviet Government, needs peace so urgently that it is ready to resort to nuclear weapons, if necessary, to defend the peace to nuclear weapons, if necessary, to defend the peace against fascist aggression. And we can lick the man who says it isn’t so.”

Friends, I hope you won’t find this amusing, because I believe it is an accurate paraphrase of the words I heard in the Soviet Union—again, and again, and again. Words that I heard without a sound of dissent, except that one voice, which was not a sound, but rather a secret note passed to Bradford Lyttle at the Moscow University meeting, while the words I have just paraphrased were ringing through the hall—a secret note which read in full:

My dear friends, do not believe absolutely this dirty official and his common demagogic phrases. Go you path, we are with you.

When I remember these words—the shouted words and the silent words—it makes me angry to hear people in our peace movement gloating and saying, “For years we have been told to go tell it to the Russians, and now we can say we have gone and have ‘told it to the Russians.’”

I am not going to lie to you.

I hope that you will not say that I have been to the Soviet Union.

I hope that you will not say that you have been there.

I hope you will not say that our ideas have been presented there.

The fact is that we have not touched the Soviet Union.

We flicked in and out of the Soviet Union so fast that we hardly knew we were there. Our hosts had us so tied up in knots we had to roll along the ground from Brest to Moscow.

Hear a parable of the sower and the seed: A sower went out to sow, and as he sowed, some of the seed fell by the roadside, and the birds of the air devoured it as soon as it fell. Other seed fell on shallow, rocky ground, and it sprang up quickly, but it had no roots.

When the drought came, it withered and died. And finally other seed fell on good ground, and when it had taken root it grew and yielded fruit a hundredfold.

Now hear an explanation of this parable: The seed that fell by the roadside and was devoured by birds is those eighty thousand leaflets we distributed and those talks to villagers along the roadside.

We sowed the wind, and we reaped the wind. The seed that fell among briars is those public meetings you heard about where the party liners sprang to their feet and strangled our message with a barrage of words almost before we had finished speaking.

The seed that fell on shallow rocky soil is that meeting at the Moscow University, where the students heard our message so eagerly and yet had not the courage to speak out a word of dissent from official policy, even when we were there, but had to pass up their dissent in secret notes.

How will they grow when the water leaves them? As for the seed that fell on good ground, I do not know that it was ever sown. We haven’t touched the Soviet Union with our ideas. Perhaps not much more than Richard Nixon touched it in his famous kitchen debate. The Soviet Union is still virgin soil. Before you can sow the good soil, you have to plow the ground. And I mean plow the ground. And once having set your hand to the plow you must not turn back.

I have told you that we haven’t touched the Soviet Union yet. And how could we hope to touch them when we haven’t touched ourselves yet? How could we hope to reach them with our message, when we haven’t even reached our own souls through the fat layers of our American existence?

If we want to reach them, we have to go and reach them.

If we want to speak with them, we have to go and speak with them.

And if we want to live in peace with them, we have to go and live in peace with them, personally disarmed, in labor and in poverty, again, and again, and again!