Personal and Family

( This is an outline of key people and events in my personal and family life. All are described in more detail in my autobiography, Positively Dazzling Realism. Themes and events in my life of public activism are broadly covered on other pages of this website. )

I was born on June 30, 1937 in a cabin in the woods, near the town of Mountain, Wisconsin, in the Nicolet National Forest, just north of the Menominee indigenous people's reservation.

My father, William H. Meyer, (12/29/1914-12/16/1983), was at that time a recent graduate of Pennsylvania State School of Forestry, working as a forester with the Civilian Conservation Corps, supervising the planting of trees at the Forest. He was born and raised in Philadelphia, PA.

My mother, Bertha Laros Meyer, (8/17/1911-7/27/2002) was born and raised in Northampton, PA, and was a recent graduate of Ursinus College.

My brother, William Laros Meyer, was born in Keyser, West Virginia, on May 27, 1936. He has a PhD. In biochemistry and taught for many years at the University of Vermont.

My sister, Kristin Elaine (Meyer) Warner, was born on February 3, 1939, at Freehold, New Jersey. She was a graduate of Pennsylvania State University, and taught for many years in Farmville, VA grade schools. She died on December 9, 2017. Her husband, Stanley Warner, was a forester with the Virginia Department of Forestry.

Our father was moved frequently in those years in his work for the U.S. Forest Service. In the early forties we moved to Poultney, Vermont, where Dad worked as a county agent for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In 1945 our parents bought a sixteen-acre swath of pasture and meadow, with a seventeen-room house, built in 1812, in the village of West Rupert in southwestern Vermont. White Creek wound diagonally through the center of our property.

In the following years, before we children went off to college, our family developed this land as very beautiful garden and arboretum, planting small groves of diverse trees, shrubs, and food bearing plants. This life was the source of my environmental awareness, and interest in urban agriculture, that led to creating the Nashville Greenlands community many years later.

Soon after moving to West Rupert we were joined there by Dad's parents and maiden aunt - J. Henry Meyer, Mary Pauline (Baumann) Meyer, and Sophie Baumann. They were children of first generation, 19th Century, German immigrants to the United States.

My father, William H. Meyer, (12/29/1914-12/16/1983), was at that time a recent graduate of Pennsylvania State School of Forestry, working as a forester with the Civilian Conservation Corps, supervising the planting of trees at the Forest. He was born and raised in Philadelphia, PA.

My mother, Bertha Laros Meyer, (8/17/1911-7/27/2002) was born and raised in Northampton, PA, and was a recent graduate of Ursinus College.

My brother, William Laros Meyer, was born in Keyser, West Virginia, on May 27, 1936. He has a PhD. In biochemistry and taught for many years at the University of Vermont.

My sister, Kristin Elaine (Meyer) Warner, was born on February 3, 1939, at Freehold, New Jersey. She was a graduate of Pennsylvania State University, and taught for many years in Farmville, VA grade schools. She died on December 9, 2017. Her husband, Stanley Warner, was a forester with the Virginia Department of Forestry.

Our father was moved frequently in those years in his work for the U.S. Forest Service. In the early forties we moved to Poultney, Vermont, where Dad worked as a county agent for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In 1945 our parents bought a sixteen-acre swath of pasture and meadow, with a seventeen-room house, built in 1812, in the village of West Rupert in southwestern Vermont. White Creek wound diagonally through the center of our property.

In the following years, before we children went off to college, our family developed this land as very beautiful garden and arboretum, planting small groves of diverse trees, shrubs, and food bearing plants. This life was the source of my environmental awareness, and interest in urban agriculture, that led to creating the Nashville Greenlands community many years later.

Soon after moving to West Rupert we were joined there by Dad's parents and maiden aunt - J. Henry Meyer, Mary Pauline (Baumann) Meyer, and Sophie Baumann. They were children of first generation, 19th Century, German immigrants to the United States.

My mother's father, Dr. Albert Henry Laros, a beloved small-town family physician, had died prematurely in 1931. He was a descendant of Jean Louis de la Rose, a French Huguenot refugee, who immigrated to Pennsylvania in 1740.

My grandmother, Julia (Stahl) Laros, lived in Philadelphia. She vacationed with us occasionally in West Rupert. She was lively, funny, outspoken, and affectionate. I was very fond of her. She died of an appendicitis attack in 1955.

My grandmother, Julia (Stahl) Laros, lived in Philadelphia. She vacationed with us occasionally in West Rupert. She was lively, funny, outspoken, and affectionate. I was very fond of her. She died of an appendicitis attack in 1955.

As children, we lived an idyllic village life, working summers in our gardens, running around in the surrounding hills, swimming in pools we created by damming the creek with rocks and branches. We attended grade school in a two-room brick schoolhouse, and high school a few miles across the state border in Salem, New York. We loved most of our teachers, and our teachers loved us.

My brother went off to Yale after two years of high school, with an experimental Ford Foundation "pre-induction scholarship". I left for the University of Chicago with a similar, full-tuition and room-and-board scholarship the following summer. U. of C. at that time had a unique curriculum of "General Studies", based on the "Great Books of the Western World".

In a series of examinations during the first two weeks of residence there, I received two full years of college credit, based on knowledge I had acquired during adolescence through precocious reading of historical, philosophical, and literary classics.

My brother went off to Yale after two years of high school, with an experimental Ford Foundation "pre-induction scholarship". I left for the University of Chicago with a similar, full-tuition and room-and-board scholarship the following summer. U. of C. at that time had a unique curriculum of "General Studies", based on the "Great Books of the Western World".

In a series of examinations during the first two weeks of residence there, I received two full years of college credit, based on knowledge I had acquired during adolescence through precocious reading of historical, philosophical, and literary classics.

Shortly after beginning my second year in college, I experienced several weeks of inexplicable depression, frequently considering escape from my inner conflict (to quit or stick it out) by suicide.

I finally decided to drop out, only seven months before my potential graduation. As soon as a decisive letter of explanation to my parents went into a mailbox, the depression lifted, and never returned. It made no sense to drop out, and the explanations I produced contained very little insight into what was really going on inside me.

After Christmas break, I moved to New York, rented a furnished room in Manhattan for $7 a week, and soon got a job as a stock clerk, at minimum wage, in the used college textbook department of Barnes & Noble, at 5th Avenue and 18th St., at that time their only store.

My top supervisor in that department was John Krogstad, a Vice President of B & N, who valued my work highly because of my scrupulous adherence to strict alphabetical and subject arrangement of stock on the shelves.

My dormitory House Head at U. of C., Ken Lewalski, had written to me suggesting several key books in the bibliography of progressive 20th Century Catholic social thought, including autobiographies of Dorothy Day and Ammon Hennacy, leaders in the Catholic Worker movement.

He felt these books would especially speak to my interests and ideas. After work and on weekends, I walked north to the New York Public Library, and read these, and many other books, in the main reading room.

This is where I acquired a sense of strong affinity with CW ideas.

As my 18th birthday approached, I registered as a conscientious objector under the Selective Service system of registering all young men for possible compulsory military service. I received the 1-O classification, making me eligible for two years of civilian service in lieu of military service, if drafted. (This is where my first FBI investigation file begins.)

At the library I read a number of biographical interpretations of the life of Joan of Arc, my most admired heroine, who left her village in Lorraine at the age of seventeen, with the goal of driving occupying English armies out of France and enabling the coronation of the heir to the French throne.

After accomplishing much of this mission, she was captured by enemy soldiers, and burned at the stake, at the age of nineteen, on accusations and conviction of religious heresy. Influenced by her example, I felt that I was behind the time for setting out on my own mission of rescuing the world from the looming threats of irrational militarism and nuclear war.

In early 1956 I set out for Washington, with a bare minimum of personal belongings packed in a brief case, intending to obtain interviews with President Eisenhower, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and members of the Senate, to convince them by simple reasoning that a path of honest negotiations with the Soviet Union was the way to end the "Cold War" and the race to gain dominance with nuclear weapons, that threatened all of us with annihilation. This was on one hand "Positively Dazzling Realism", and on the other, deeply naïve idealism.

After several weeks of shyly trying to get such interviews, I was running out of my savings for the project, and had to admit my failure, to myself. I took the lesson to start at the bottom with education, which became a lifetime project, rather than trying to start with influence at the top.

I easily found a job as a messenger for Covington and Burling, a prestigious law firm, where the best -known partner was Dean Acheson, former Secretary of State to President Truman.

I began attending gatherings of volunteers at Friendship House, a Catholic interracial justice movement. Influenced by Catholic Worker ideas, I rented and moved into a small storefront in the heart of a ghetto neighborhood, and had a try at sheltering homeless men, but I soon failed at that also, because of my naïve inexperience.

I received baptism in the Catholic Church on December 15, 1956, with support from the Friendship House community.

Shortly afterwards, I returned to New York and to Barnes and Noble, and began saving to reenroll at the University of Chicago in the fall of 1957.

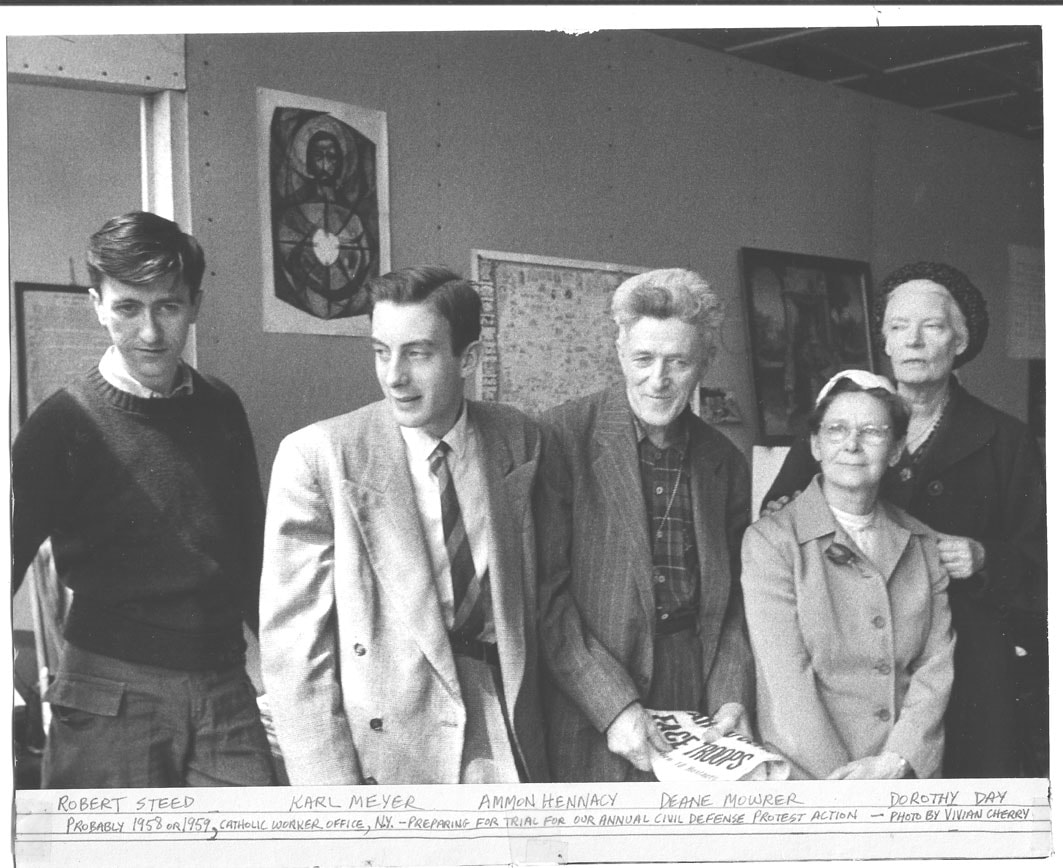

On July 12, 1957, I left work at lunchtime and raced down to the Catholic Worker house to join Dorothy Day, Ammon Hennacy, and nine others sitting in a park and refusing to take shelter during a compulsory statewide civil defense drill, supposedly to prepare to protect ourselves in the event of a massive Soviet nuclear attack on New York.

We were all arrested, and later sentenced to thirty days in jail. Legally classified at age twenty as a juvenile, I was sent alone to the notorious Riker's Island juvenile jail. (I returned in 1958 and '59 for similar action. See Ban Bomb sub-page.)

I finally decided to drop out, only seven months before my potential graduation. As soon as a decisive letter of explanation to my parents went into a mailbox, the depression lifted, and never returned. It made no sense to drop out, and the explanations I produced contained very little insight into what was really going on inside me.

After Christmas break, I moved to New York, rented a furnished room in Manhattan for $7 a week, and soon got a job as a stock clerk, at minimum wage, in the used college textbook department of Barnes & Noble, at 5th Avenue and 18th St., at that time their only store.

My top supervisor in that department was John Krogstad, a Vice President of B & N, who valued my work highly because of my scrupulous adherence to strict alphabetical and subject arrangement of stock on the shelves.

My dormitory House Head at U. of C., Ken Lewalski, had written to me suggesting several key books in the bibliography of progressive 20th Century Catholic social thought, including autobiographies of Dorothy Day and Ammon Hennacy, leaders in the Catholic Worker movement.

He felt these books would especially speak to my interests and ideas. After work and on weekends, I walked north to the New York Public Library, and read these, and many other books, in the main reading room.

This is where I acquired a sense of strong affinity with CW ideas.

As my 18th birthday approached, I registered as a conscientious objector under the Selective Service system of registering all young men for possible compulsory military service. I received the 1-O classification, making me eligible for two years of civilian service in lieu of military service, if drafted. (This is where my first FBI investigation file begins.)

At the library I read a number of biographical interpretations of the life of Joan of Arc, my most admired heroine, who left her village in Lorraine at the age of seventeen, with the goal of driving occupying English armies out of France and enabling the coronation of the heir to the French throne.

After accomplishing much of this mission, she was captured by enemy soldiers, and burned at the stake, at the age of nineteen, on accusations and conviction of religious heresy. Influenced by her example, I felt that I was behind the time for setting out on my own mission of rescuing the world from the looming threats of irrational militarism and nuclear war.

In early 1956 I set out for Washington, with a bare minimum of personal belongings packed in a brief case, intending to obtain interviews with President Eisenhower, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and members of the Senate, to convince them by simple reasoning that a path of honest negotiations with the Soviet Union was the way to end the "Cold War" and the race to gain dominance with nuclear weapons, that threatened all of us with annihilation. This was on one hand "Positively Dazzling Realism", and on the other, deeply naïve idealism.

After several weeks of shyly trying to get such interviews, I was running out of my savings for the project, and had to admit my failure, to myself. I took the lesson to start at the bottom with education, which became a lifetime project, rather than trying to start with influence at the top.

I easily found a job as a messenger for Covington and Burling, a prestigious law firm, where the best -known partner was Dean Acheson, former Secretary of State to President Truman.

I began attending gatherings of volunteers at Friendship House, a Catholic interracial justice movement. Influenced by Catholic Worker ideas, I rented and moved into a small storefront in the heart of a ghetto neighborhood, and had a try at sheltering homeless men, but I soon failed at that also, because of my naïve inexperience.

I received baptism in the Catholic Church on December 15, 1956, with support from the Friendship House community.

Shortly afterwards, I returned to New York and to Barnes and Noble, and began saving to reenroll at the University of Chicago in the fall of 1957.

On July 12, 1957, I left work at lunchtime and raced down to the Catholic Worker house to join Dorothy Day, Ammon Hennacy, and nine others sitting in a park and refusing to take shelter during a compulsory statewide civil defense drill, supposedly to prepare to protect ourselves in the event of a massive Soviet nuclear attack on New York.

We were all arrested, and later sentenced to thirty days in jail. Legally classified at age twenty as a juvenile, I was sent alone to the notorious Riker's Island juvenile jail. (I returned in 1958 and '59 for similar action. See Ban Bomb sub-page.)

After our release I was received as a valued friend and associate to Dorothy, Ammon, and many others in the Catholic Worker movement. This has remained a principal affiliation and identity for all the years since then, though I renounced faith in Christian theological doctrine and Catholic practice fifteen years later. (See Auto-Biog page for current religious beliefs.)

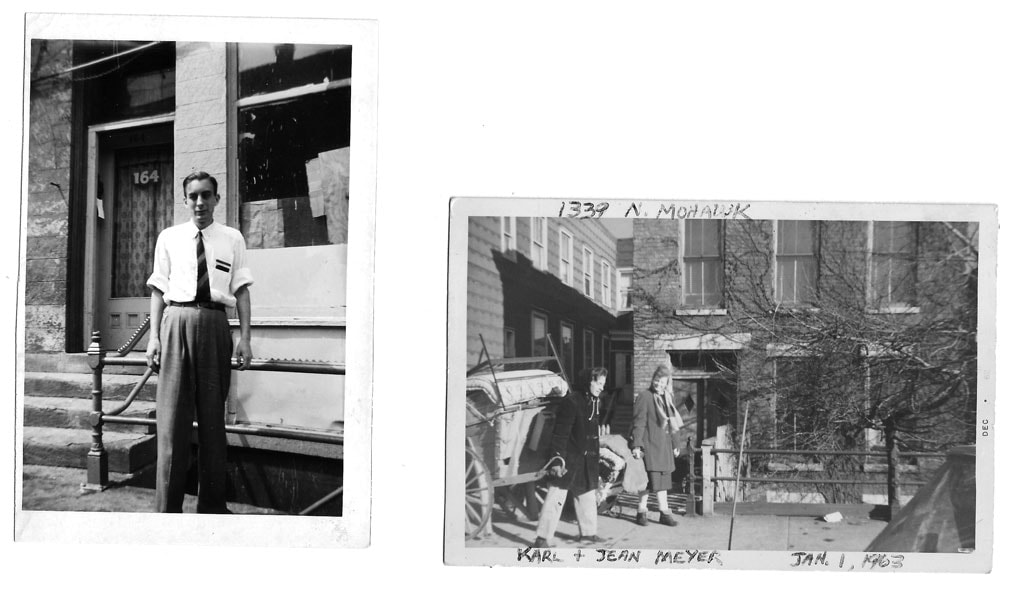

I returned to the University of Chicago, and graduated with honors in June 1958. (I lived in Chicago for the next thirty-eight years.) That summer I rented a small five room storefront, for $50 a month, in a slum tenement building at 164 West Oak St., just two blocks east of the notorious Cabrini-Green public housing project, and began housing homeless men. I shared my household with them for the next fourteen years. (See What Is to Be Done on the Housing Homeless page.)

I returned to the University of Chicago, and graduated with honors in June 1958. (I lived in Chicago for the next thirty-eight years.) That summer I rented a small five room storefront, for $50 a month, in a slum tenement building at 164 West Oak St., just two blocks east of the notorious Cabrini-Green public housing project, and began housing homeless men. I shared my household with them for the next fourteen years. (See What Is to Be Done on the Housing Homeless page.)

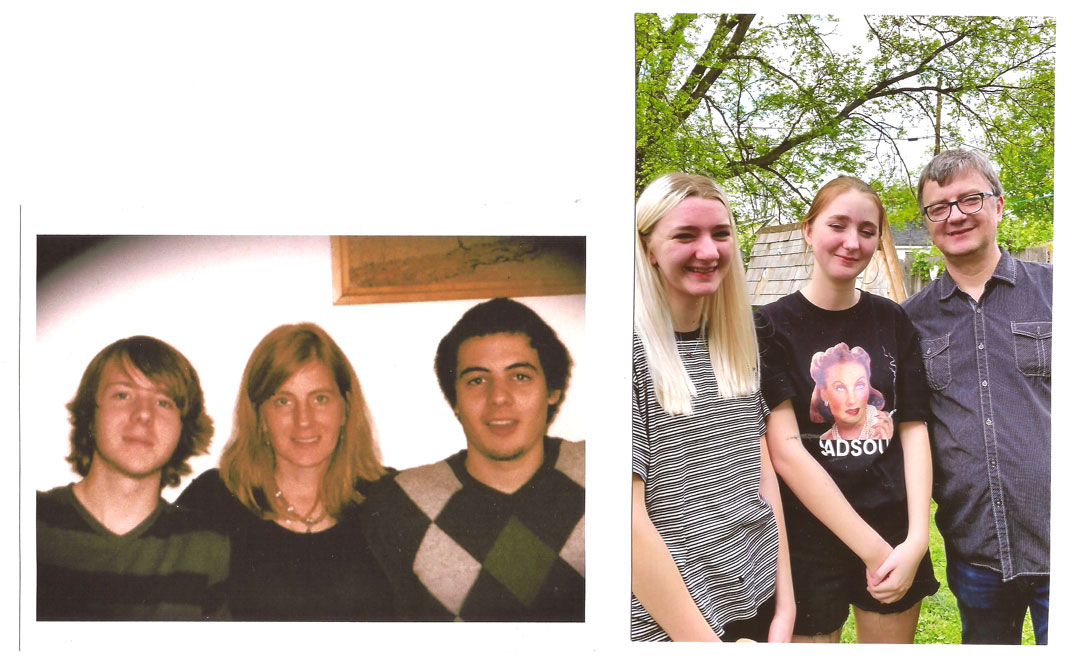

In 1962 I married Jean Francis, a kind and lovely woman. We bought a small two-flat house at 1339 Mohawk St., and shared it with a half-dozen men from my Oak St. shelter. Our son, William Wallace Meyer, was born on February 20, 1964, a daughter, Kristin Lara Meyer, on June 11, 1967, and a son, Eric Alder Meyer, on December 24, 1970.

My father, William H. Meyer, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1958 as the sole Congressman representing the State of Vermont. He quickly became highly respected among U.S. peace movements for his resolute opposition to militarism, Cold War foreign policy, and nuclear weapons.

In a personal letter accompanying a donation to his 1960 re-election campaign, his colleague George McGovern, later the Democratic party candidate for President in 1972, called my father "the conscience of us all…"

Dad lost his re-election race when Richard Nixon easily defeated John F. Kennedy for Vermont's Electoral College votes.

In the years between 1957 and 1975 I earned my living successively as a retail clerk at Follett's College Bookstore, an order picker at an A.C. McClurg warehouse, a supervisor and manager of sheltered workshops for two agencies serving mentally retarded and mentally ill adults, and as a patient unit manager at the University of Illinois Hospital.

Jean was discontented and never very comfortable in our relationship. In February 1975, having received a modest inheritance on the death of her father, she moved to Evanston, a Chicago suburb, with our children. Later, Kristin and Eric remained living with her, while William came to live with me for the balance of his adolescence. In May 1978, Jean and I formally divorced.

In October 1975 I was pushed out of my job at the Chicago School and Workshop for the Retarded, essentially, I believe, because of my support of unionization for supervisory staff in our workshops, although other grievances were used as a pretext.

In November I found work as a carpentry helper, began to learn carpentry skills, and have earned my living as a remodeling and repair carpenter for all the years since, up to the present.

The Vietnam War ended in 1975, and I devoted most of the next five years to work and personal life. Between 1975 and my second marriage in 1982, I had love relationships with a number of very fine and lovely women. Some are introduced in vignettes, using pseudonyms, in my autobiography. (A chapter, "On Loving", follows this summary of personal life.)

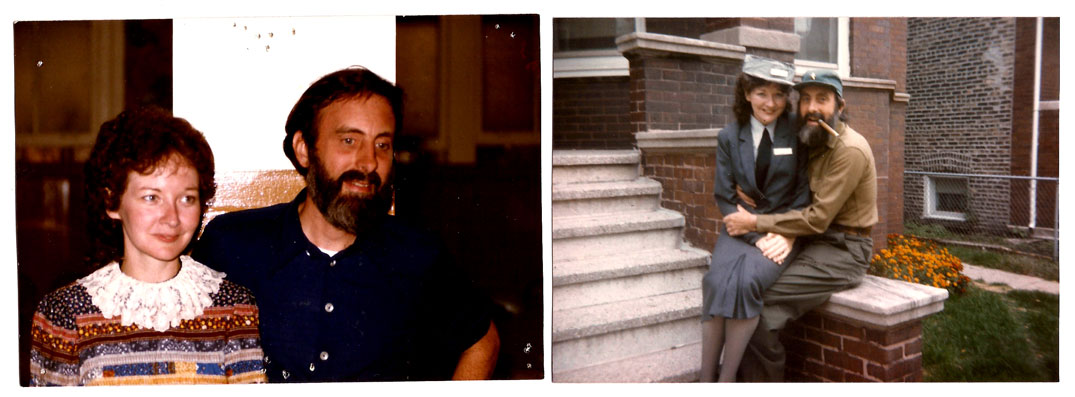

I met Kathy Kelly serving at a Catholic Worker soup kitchen meal program in Uptown Chicago. We began dating in 1980, and married on July 22, 1982. She is an exceptionally kind, generous, tolerant, and courageous person.

Documents and photographs from our highly cooperative engagement on issues of world peace in the 1980s and '90s are posted on the End War and Peace House pages of this website.

In a personal letter accompanying a donation to his 1960 re-election campaign, his colleague George McGovern, later the Democratic party candidate for President in 1972, called my father "the conscience of us all…"

Dad lost his re-election race when Richard Nixon easily defeated John F. Kennedy for Vermont's Electoral College votes.

In the years between 1957 and 1975 I earned my living successively as a retail clerk at Follett's College Bookstore, an order picker at an A.C. McClurg warehouse, a supervisor and manager of sheltered workshops for two agencies serving mentally retarded and mentally ill adults, and as a patient unit manager at the University of Illinois Hospital.

Jean was discontented and never very comfortable in our relationship. In February 1975, having received a modest inheritance on the death of her father, she moved to Evanston, a Chicago suburb, with our children. Later, Kristin and Eric remained living with her, while William came to live with me for the balance of his adolescence. In May 1978, Jean and I formally divorced.

In October 1975 I was pushed out of my job at the Chicago School and Workshop for the Retarded, essentially, I believe, because of my support of unionization for supervisory staff in our workshops, although other grievances were used as a pretext.

In November I found work as a carpentry helper, began to learn carpentry skills, and have earned my living as a remodeling and repair carpenter for all the years since, up to the present.

The Vietnam War ended in 1975, and I devoted most of the next five years to work and personal life. Between 1975 and my second marriage in 1982, I had love relationships with a number of very fine and lovely women. Some are introduced in vignettes, using pseudonyms, in my autobiography. (A chapter, "On Loving", follows this summary of personal life.)

I met Kathy Kelly serving at a Catholic Worker soup kitchen meal program in Uptown Chicago. We began dating in 1980, and married on July 22, 1982. She is an exceptionally kind, generous, tolerant, and courageous person.

Documents and photographs from our highly cooperative engagement on issues of world peace in the 1980s and '90s are posted on the End War and Peace House pages of this website.

As our activities and ways of life diverged substantially, we divorced in December 1994, but she remains one of my most loved and respected friends.

She was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2000, 2001 and 2003, for her work in leading delegations of peace workers and journalists to Iraq, and bringing world awareness to the deadly effects of an oils sales embargo and economic sanctions in causing the death of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi children and other civilians between the 1991 and 2003 Iraq wars.

Her current actions, as of 2020, are centered on humanitarian aid and ending the wars in Afghanistan and Yemen.

She was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2000, 2001 and 2003, for her work in leading delegations of peace workers and journalists to Iraq, and bringing world awareness to the deadly effects of an oils sales embargo and economic sanctions in causing the death of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi children and other civilians between the 1991 and 2003 Iraq wars.

Her current actions, as of 2020, are centered on humanitarian aid and ending the wars in Afghanistan and Yemen.

Grandchildren

Tyler Jean Meyer, born January 6, 1990, St. Paul, MN, and Felix Anthony Meyer, born September 30, 1994, to my daughter Kristin.

Abigail Francis Meyer, born August 30 1997, New York City, and Sadie Elizabeth Meyer, born September 1, 2000, New York City, to Anna Brackett and my son William.

Abigail Francis Meyer, born August 30 1997, New York City, and Sadie Elizabeth Meyer, born September 1, 2000, New York City, to Anna Brackett and my son William.

In December 1996 I moved to Nashville, Tennessee, bought a vacant house, and began the Nashville Greenlands experiment in urban agriculture and community building, documented by the Greenlands page on this website.

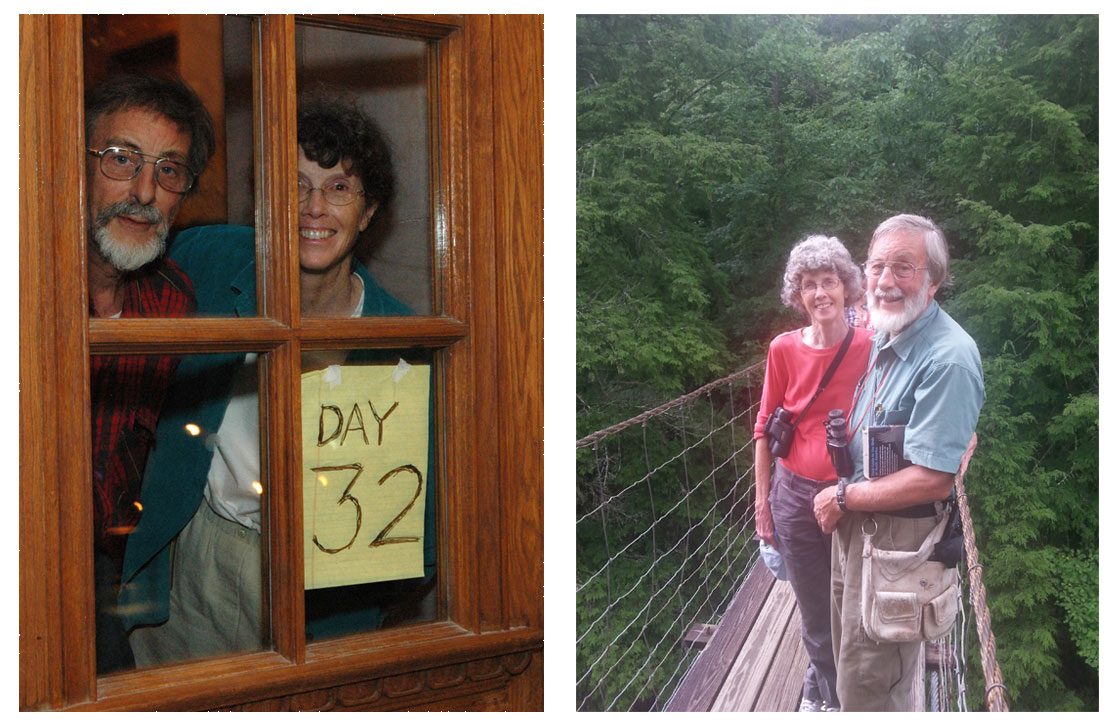

In 1998 Pamela Beziat and I began dating and became partners in personal relationship and in developing the Greenlands community network, now encompassing seven affiliated houses owned and populated largely by peace and social justice activists.

In 1998 Pamela Beziat and I began dating and became partners in personal relationship and in developing the Greenlands community network, now encompassing seven affiliated houses owned and populated largely by peace and social justice activists.

----- Karl & Pam 7-21-2005 (Photo - Al Levenson)------------------------Pam and Karl June 30, 2014---------------------- ------through State Capitol window, day 32 of 71 Day Peace & Justice sit-in------------Birding at Fall Creek

State Park --------------------

protesting cuts to state healthcare benefits--------------------------------------------------------

----- Karl & Pam 7-21-2005 (Photo - Al Levenson)------------------------Pam and Karl June 30, 2014---------------------- ------through State Capitol window, day 32 of 71 Day Peace & Justice sit-in------------Birding at Fall Creek

State Park --------------------

protesting cuts to state healthcare benefits--------------------------------------------------------

CHAPTER EXCERPTED FROM POSITIVELY DAZZLING REALISM

On Loving

In these years of looking for love between 1975 and 1980, I found more love with more lovely people than I could possibly do justice to. I was not afraid of marriage or long-term commitment, but I remained clear that I would marry only if both of us felt sure about each other. I developed my own ethic and definition of faithfulness: that I would remain loyal to those I loved and faithful to my friendship with them on whatever terms they desired and chose.

If they wanted to continue a sexual relationship with me, I continued it. If they wanted to remain friends on other terms, I accepted the terms that they defined. But I would not let one lover or friend dictate the terms of my relationship with another. In this way, each of my enduring love-friendships evolved and developed.

One part of me has felt that I should not tell so much of my personal life, my complicated search for a personal solution to the problems of love and commitment. I flouted the prevailing public morals of our culture, and reached ethical conclusions about sexuality different from the accepted norm.

To tell about it could invite a load of disapproval. I encountered plenty of anger and disapproval along the way from those who strongly believe and feel that we are to be owned by those we love, including most of my lovers at one time or another.

None of this pilgrimage would be seen as noble by most people, or even by myself. It might seem more noble to find one true love without any stumbling in the light, to feel sure for the rest of one's life, to earn congratulations from Paul Harvey after sixty years of marriage.

To tell the truth might undermine the apparent nobility of my years of struggle for peace and justice.

On the other hand, what is the point of writing an autobiography or biography if one does not dare to tell the truth, especially in those areas of life that are least openly discussed, and most difficult to discuss?

We want to know how others have handled the questions we face. That is why we read honest biographies with such fascination.

I have felt less confidence in my personal ethic of non-possessive love and sexuality, than in my ethic of nonviolence and the equitable sharing of economic resources. Few of those close to me have reproached me for refusing to go to war, to kill or harm others.

Fewer still, even in the culture at large, have criticized me for sharing my home and my livelihood with others in need, or for respecting the biological environment of Earth. It has been harder to discover and defend my own ethic of love, sometimes against the reproaches of those whose understanding and approval I desired most, my lovers and my children.

I found and followed my own heart and conscience. I cannot accept the moral authority of a culture that spends trillions of dollars of the world's vital resources on weapons of mass destruction, that uses such weapons over and over against the innocent, that devastates the sacred biological heritage of Earth for the sake of accumulating vast material wealth, that validates and protects huge accumulations of wealth while millions go without food, health care, education, shelter, and other essentials for a fulfilled life.

I cannot accept the moral wisdom of such a culture, that intimacy and sexual love, also, should not be generously and freely shared.

I should mention here two important rules that I have consistently followed:

Firstly, in all the relationships of life, I very seldom lie about anything. I may withhold or conceal information that other people might want to have, if it would seem harmful for me or others to disclose it, but I am rarely maneuvered into a situation where I violate my ethic against telling lies.

In personal love relationships with women, I tell the truth about myself. I tell them where I see myself in relation to them and to others who may be in my life. I tell them in the beginning before we get involved. Of course, I do not disclose everything about my feelings that another person might prefer to know, but often I disclose more than they want to know.

I do not lie about anything they ask me; if I refuse to answer to protect the privacy of another, I tell them why I will not answer.

Since this level of honesty is not usual, they may not believe me until they know me better. Most learn to trust me more the longer they know me. Few people are as open with me as I am with them. So much of our social training fosters self-protection through concealment or dishonesty, including dishonesty to ourselves.

I make earnest efforts to encourage others to be open with me, and I try to avoid punishing them for telling me the truth. As a consequence, most women in love relationships have been truthful with me.

I cannot think of any instances where I felt harmed or wronged by intentional lying or deception, although I have been misled many times by not knowing about concealed feelings or undisclosed intentions.The ethic of love that I believe in is not possible without honesty.

The other rule is that I almost always use condoms and use them carefully, to prevent unintended pregnancies and protect against sexually transmitted diseases. In the first years of marriage, when I was a rule-abiding Catholic, we used the rhythm method for spacing the birth of children we intended to have.

In more than thirty years after, there were probably less than five times when I ever had sexual intercourse without using a condom. In those few situations, it was with someone I knew so well that I was virtually certain there was no risk from either of us. I have no knowledge of ever receiving or transmitting a sexual disease, apart from whatever role I may have had in contributing to yeast infections.

On two occasions, I got crab lice from women I knew who were sexually involved with other men; in one case, I passed them on to one other person before we discovered them and got rid of them.

To put this history in perspective, over those same years, I frequently contracted non-sexual contagious diseases such as colds, flu, and throat infections. I also contracted tuberculosis, a dangerous contagious disease that cost me over a year of treatment and convalescence, and I undoubtedly exposed a number of other people before I discovered I had it.

People dread sexually transmitted diseases more than other contagious and infectious diseases, because of the shame and embarrassment involved. With care, they can be avoided more easily than many other contagious diseases.

In the years between Jean's separation from me in 1975 and my second marriage seven years later, I dated many women and had sexual love affairs of shorter or longer duration with fifteen of them.

Through the evolution of my experience in these relationships, I came to a set of beliefs and values about love, sexuality, and marriage that is as radically different from the prevailing accepted mores of our culture as are my beliefs about the best road to justice and peace.

The prevailing mores are derived from the Christian ethic of marriage, as it applied to earlier systems in which women were treated as the property of men.

Both systems were based on the concept of exclusive possession of persons. Where older contracts of marriage gave men the exclusive possession of women, along with various obligations to them, the Christian marriage contract attempted to give to each the exclusive possession of the sexual expression of the other, until death parted them. Protestantism allowed for the dissolution of this contract.

The de facto relaxation of standards for marriage and cohabitation allowed for informal verbal and tacit agreements of shorter or indefinite duration. But the idea of the rightfulness of jealous possession remains strong in the culture. To depart from the exclusive possession of the other person is called "infidelity."

In many ways, this is analogous to the cultural belief in the ownership of land and other real property. In America today, all land, all dwellings, and almost all other physical objects and property are owned by someone, and the recognized owner has the right to exclude all others from using them, no matter how much property he has, or whether he is using it or intends to use it at all.

In the Catholic Worker movement, recognizing the dominance of this system, we accepted the ownership or stewardship of dwelling places, but if we had extra rooms, we shared them with others. With respect to all forms of wealth and property, we endorsed the communal ideal "from each according to ability; to each according to need." When I was a boy roaming the hills of Vermont with Pal and Blackie, many fence lines we came to had signs posted on trees, "No Trespassing."

It is even more common today. In a seldom used verse of Woody Guthrie's famous song, "This Land is Your land," he sang, "As I was walking that ribbon of highway…Was a great big sign there says “Private Property’, but on the other side it didn't say nothin’ - that side was made for you and me."

By the 1970s, I was one of the most notorious trespassers of my day, having been arrested and expelled or jailed for trespassing around the world, at places ranging from missile bases to public buildings and even subway platforms. As an anarchist socialist, I rejected the concept of exclusive ownership of any property that people weren't directly using themselves, that might be needed and used by others who had none.

In my marriage with Jean, I began by accepting the Catholic idea of the enduring mutual possession of two persons in marriage. That did not work for Jean as she increasingly discovered that she did not love me. I saw her love for Lemont and later for Bodin, and I accepted it without much jealousy or reproach.

They were both friends of mine, isolated by their unusual journeys in life, and I loved them both. The thing that bothered me was that she did not love me also, in a way that was adequate to my longings. I don't know if I have ever met another person as faithful and loyal in friendship as I am.

Perhaps it is because I had few personal friends beyond my family as a child. I hang onto significant friendships with both men and women for a long time. My con-man friends, John and Larry, rejected by so many others, could always come back to me. I keep writing at least annually to over a hundred friends, many of whom may never reply, or reply only occasionally after lapses of many years. The only reason the number is not more is because so many have been lost when they moved and mail forwarding expired.

When I began dating and forming love relationships after Jean's separation from me, I was with women whom I loved very much. Yet, sometimes when I got to know them, I reasonably concluded that we were not right for living together or marriage or for a primary partnership; as often, it was they who reached this conclusion about me.

Even as we drew apart, or sought more fulfilling relationships, I found myself unwilling to drop the other person cold or abandon her. In an analogy to the doctrine of the Communion of Saints, which was so appealing to me in the creed of Catholicism, I continue to hold each one of these lovers in a shrine within my heart, which I return to often in memory, love, and gratitude.

I think that I have never turned away from a lover for long in anger. I cannot remember ever refusing a phone call, or avoiding a call or not returning a call from any of these lovers. I do not believe that I have returned a letter, or failed to reply to a letter, seeking to reach an honest understanding of our mutual needs with any who wished to do this.

There is not a woman that was ever my lover that I would not receive again with great delight and warmth, and welcome again as my friend. It is a commonly expressed belief in contemporary women's writing about men, that men are emotionally closed and will not talk about their inner feelings, hopes and needs, with the women they love.

I do not doubt that this is so for many men, but I know it is not so for me. The myth is that women do express their feelings. It is my experience that I have had to persuade and coax almost every woman I have ever been close to, to disclose her real feelings, beliefs, and needs to me, and many are quite unable to do that, much of the time.

I have tried to be honest myself, but often it is very hard to be honest if one fears that honesty will cause pain to the other or loss to oneself. Of the many lovers I have had, I remain in regular communication with twelve of them, and as close friends I would say with seven, as well as with a number of others with whom I have never had a sexual love affair.

Some lovers have broken off from me, probably in pain, refusing to communicate with me again, and most often without ever really telling me why they did it. I believe it has usually been over issues of jealousy and possession.

They have not reproached me with being unkind, thoughtless, inattentive, or dishonest to them. If they were bothered or angry, it was not with who I was when I was with them or even that I was not with them as they wanted me to be. They were bothered about what my relationship with other women might be when I was not with them, or that they could not have with me the relationship they desired, living together, being married, or having children with me.

It seems to me a testimony to the intensity of my fidelity and loyalty, that I would not agree to turn away from those I had loved before and be possessed by one new person alone; that has been an obstacle to some women who loved me most and whom I in turn loved deeply.

In an existential journey from the ideal of Catholic marriage to the principle of free love, I came to believe that I would not consent to be exclusively possessed in love by any person; I would not form my primary love relationship with any woman who could not accept this. Thus it has been that my most enduring primary love relationships, with my second wife and with my present companion, have been with women who accepted this in me, and remain my two closest friends.

I regret that I cannot name other women I have loved so much. Something in me wants to use the names by which I know them, but I cannot do this in faithfulness to them, because too often some have made clear to me that they wanted confidentiality.

If I name people here with a first name and a surname (other than my first wife, Jean, who has died), they have consented to be named. If I name them only with a first name, it is a pseudonym used for the fluency of the narrative, but concealing their identity.

A few more words in general about the psychology of loving and the arithmetic of loving: sexual relations are not the highest form of intimacy, although I have found that they have always intensified the bond of loving for me.

Still, it can be quite easy to have sex without intimacy. I have tried sex with prostitutes on a number of occasions. I have always treated them with the respect and affection that is due to people practicing a profession that is so often demeaning and so widely despised. However, it is always quite unsatisfactory, because the mutuality of desire and loving are not present.

The highest form of intimacy is the open communication of honest friendship, if we finally dare to tell another person who we really are, and, even, almost understand the soul of the other. That is far more difficult and more rare than the pleasure of loving sexual relationships.

The great love of your life is not the one with whom you have sex, but the one with whom you finally dare to talk and tell the truth about yourself.

In the psychology of the human, it is seldom possible to find all forms of satisfaction and fulfillment in the love of one person. I don't understand why in loving we should even attempt to find one person who would meet all our complex emotional needs, while at the same time we meet all of theirs. We don't expect this in any other form of friendship.

Finally, the arithmetic of loving – the design of nature is such that in every community of a thousand births, about half are women, about half are men. But the actuarial fact of differentials in death rates, homosexual inclinations and vocations to abstinence or celibacy, leave us always uncertain as to how many women may be seeking heterosexual pairings, and how many men are seeking the same. Let us say that in some theoretical sample of one thousand, there are four hundred women wanting pairings with four hundred willing men.

Let us say that after much seeking and thrashing around in the dark, there emerges the improbable total of three hundred and fifty reasonably happy and reasonably stable monogamous pairings. That leaves fifty still seeking among fifty possible partners.

The problem is that the most attractive and the easiest to please are already paired with one another, while the most difficult to please and the least able to please are still left seeking the perfect pairing with another.

If we had an ethic of loving that allowed or encouraged each person to have two love partners, or even three, there would then be twelve hundred possible pairings among the four hundred women and four hundred men and each person would have three times the chance of finding at least one other person to love, and be loved by.

I believe that our refusal to share our lovers with others springs from the same spirit of possessiveness and greed that leads one person with money to live alone in a ten room house, while others with nothing live homeless on the streets; or one person with money lays claim to thousands or even millions of acres of land, that Earth and nature created over the course of billions of years, while the disinherited of Earth have no land even to feed their families.

Finally, let me say that in the evolution of my own ethic of love in the mid 70s, I was helped by reading several books:

Rollo May - Paulus is a humanistic psychologist's memoir on the issue of love in the life of his friend, the famous Protestant theologian, Paul Tillich.

Hannah Tillich - From Time to Time is the autobiography of Paul Tillich's wife, Hannah.

Simone de Beauvoir - biographies of the author of The Second Sex, who was a lover of Jean Paul Sartre and Nelson Algren, among others.

Emma Goldman - Living My Life, two volume autobiography of a famous turn of the 19th Century anarchist and advocate of free love.

If they wanted to continue a sexual relationship with me, I continued it. If they wanted to remain friends on other terms, I accepted the terms that they defined. But I would not let one lover or friend dictate the terms of my relationship with another. In this way, each of my enduring love-friendships evolved and developed.

One part of me has felt that I should not tell so much of my personal life, my complicated search for a personal solution to the problems of love and commitment. I flouted the prevailing public morals of our culture, and reached ethical conclusions about sexuality different from the accepted norm.

To tell about it could invite a load of disapproval. I encountered plenty of anger and disapproval along the way from those who strongly believe and feel that we are to be owned by those we love, including most of my lovers at one time or another.

None of this pilgrimage would be seen as noble by most people, or even by myself. It might seem more noble to find one true love without any stumbling in the light, to feel sure for the rest of one's life, to earn congratulations from Paul Harvey after sixty years of marriage.

To tell the truth might undermine the apparent nobility of my years of struggle for peace and justice.

On the other hand, what is the point of writing an autobiography or biography if one does not dare to tell the truth, especially in those areas of life that are least openly discussed, and most difficult to discuss?

We want to know how others have handled the questions we face. That is why we read honest biographies with such fascination.

I have felt less confidence in my personal ethic of non-possessive love and sexuality, than in my ethic of nonviolence and the equitable sharing of economic resources. Few of those close to me have reproached me for refusing to go to war, to kill or harm others.

Fewer still, even in the culture at large, have criticized me for sharing my home and my livelihood with others in need, or for respecting the biological environment of Earth. It has been harder to discover and defend my own ethic of love, sometimes against the reproaches of those whose understanding and approval I desired most, my lovers and my children.

I found and followed my own heart and conscience. I cannot accept the moral authority of a culture that spends trillions of dollars of the world's vital resources on weapons of mass destruction, that uses such weapons over and over against the innocent, that devastates the sacred biological heritage of Earth for the sake of accumulating vast material wealth, that validates and protects huge accumulations of wealth while millions go without food, health care, education, shelter, and other essentials for a fulfilled life.

I cannot accept the moral wisdom of such a culture, that intimacy and sexual love, also, should not be generously and freely shared.

I should mention here two important rules that I have consistently followed:

Firstly, in all the relationships of life, I very seldom lie about anything. I may withhold or conceal information that other people might want to have, if it would seem harmful for me or others to disclose it, but I am rarely maneuvered into a situation where I violate my ethic against telling lies.

In personal love relationships with women, I tell the truth about myself. I tell them where I see myself in relation to them and to others who may be in my life. I tell them in the beginning before we get involved. Of course, I do not disclose everything about my feelings that another person might prefer to know, but often I disclose more than they want to know.

I do not lie about anything they ask me; if I refuse to answer to protect the privacy of another, I tell them why I will not answer.

Since this level of honesty is not usual, they may not believe me until they know me better. Most learn to trust me more the longer they know me. Few people are as open with me as I am with them. So much of our social training fosters self-protection through concealment or dishonesty, including dishonesty to ourselves.

I make earnest efforts to encourage others to be open with me, and I try to avoid punishing them for telling me the truth. As a consequence, most women in love relationships have been truthful with me.

I cannot think of any instances where I felt harmed or wronged by intentional lying or deception, although I have been misled many times by not knowing about concealed feelings or undisclosed intentions.The ethic of love that I believe in is not possible without honesty.

The other rule is that I almost always use condoms and use them carefully, to prevent unintended pregnancies and protect against sexually transmitted diseases. In the first years of marriage, when I was a rule-abiding Catholic, we used the rhythm method for spacing the birth of children we intended to have.

In more than thirty years after, there were probably less than five times when I ever had sexual intercourse without using a condom. In those few situations, it was with someone I knew so well that I was virtually certain there was no risk from either of us. I have no knowledge of ever receiving or transmitting a sexual disease, apart from whatever role I may have had in contributing to yeast infections.

On two occasions, I got crab lice from women I knew who were sexually involved with other men; in one case, I passed them on to one other person before we discovered them and got rid of them.

To put this history in perspective, over those same years, I frequently contracted non-sexual contagious diseases such as colds, flu, and throat infections. I also contracted tuberculosis, a dangerous contagious disease that cost me over a year of treatment and convalescence, and I undoubtedly exposed a number of other people before I discovered I had it.

People dread sexually transmitted diseases more than other contagious and infectious diseases, because of the shame and embarrassment involved. With care, they can be avoided more easily than many other contagious diseases.

In the years between Jean's separation from me in 1975 and my second marriage seven years later, I dated many women and had sexual love affairs of shorter or longer duration with fifteen of them.

Through the evolution of my experience in these relationships, I came to a set of beliefs and values about love, sexuality, and marriage that is as radically different from the prevailing accepted mores of our culture as are my beliefs about the best road to justice and peace.

The prevailing mores are derived from the Christian ethic of marriage, as it applied to earlier systems in which women were treated as the property of men.

Both systems were based on the concept of exclusive possession of persons. Where older contracts of marriage gave men the exclusive possession of women, along with various obligations to them, the Christian marriage contract attempted to give to each the exclusive possession of the sexual expression of the other, until death parted them. Protestantism allowed for the dissolution of this contract.

The de facto relaxation of standards for marriage and cohabitation allowed for informal verbal and tacit agreements of shorter or indefinite duration. But the idea of the rightfulness of jealous possession remains strong in the culture. To depart from the exclusive possession of the other person is called "infidelity."

In many ways, this is analogous to the cultural belief in the ownership of land and other real property. In America today, all land, all dwellings, and almost all other physical objects and property are owned by someone, and the recognized owner has the right to exclude all others from using them, no matter how much property he has, or whether he is using it or intends to use it at all.

In the Catholic Worker movement, recognizing the dominance of this system, we accepted the ownership or stewardship of dwelling places, but if we had extra rooms, we shared them with others. With respect to all forms of wealth and property, we endorsed the communal ideal "from each according to ability; to each according to need." When I was a boy roaming the hills of Vermont with Pal and Blackie, many fence lines we came to had signs posted on trees, "No Trespassing."

It is even more common today. In a seldom used verse of Woody Guthrie's famous song, "This Land is Your land," he sang, "As I was walking that ribbon of highway…Was a great big sign there says “Private Property’, but on the other side it didn't say nothin’ - that side was made for you and me."

By the 1970s, I was one of the most notorious trespassers of my day, having been arrested and expelled or jailed for trespassing around the world, at places ranging from missile bases to public buildings and even subway platforms. As an anarchist socialist, I rejected the concept of exclusive ownership of any property that people weren't directly using themselves, that might be needed and used by others who had none.

In my marriage with Jean, I began by accepting the Catholic idea of the enduring mutual possession of two persons in marriage. That did not work for Jean as she increasingly discovered that she did not love me. I saw her love for Lemont and later for Bodin, and I accepted it without much jealousy or reproach.

They were both friends of mine, isolated by their unusual journeys in life, and I loved them both. The thing that bothered me was that she did not love me also, in a way that was adequate to my longings. I don't know if I have ever met another person as faithful and loyal in friendship as I am.

Perhaps it is because I had few personal friends beyond my family as a child. I hang onto significant friendships with both men and women for a long time. My con-man friends, John and Larry, rejected by so many others, could always come back to me. I keep writing at least annually to over a hundred friends, many of whom may never reply, or reply only occasionally after lapses of many years. The only reason the number is not more is because so many have been lost when they moved and mail forwarding expired.

When I began dating and forming love relationships after Jean's separation from me, I was with women whom I loved very much. Yet, sometimes when I got to know them, I reasonably concluded that we were not right for living together or marriage or for a primary partnership; as often, it was they who reached this conclusion about me.

Even as we drew apart, or sought more fulfilling relationships, I found myself unwilling to drop the other person cold or abandon her. In an analogy to the doctrine of the Communion of Saints, which was so appealing to me in the creed of Catholicism, I continue to hold each one of these lovers in a shrine within my heart, which I return to often in memory, love, and gratitude.

I think that I have never turned away from a lover for long in anger. I cannot remember ever refusing a phone call, or avoiding a call or not returning a call from any of these lovers. I do not believe that I have returned a letter, or failed to reply to a letter, seeking to reach an honest understanding of our mutual needs with any who wished to do this.

There is not a woman that was ever my lover that I would not receive again with great delight and warmth, and welcome again as my friend. It is a commonly expressed belief in contemporary women's writing about men, that men are emotionally closed and will not talk about their inner feelings, hopes and needs, with the women they love.

I do not doubt that this is so for many men, but I know it is not so for me. The myth is that women do express their feelings. It is my experience that I have had to persuade and coax almost every woman I have ever been close to, to disclose her real feelings, beliefs, and needs to me, and many are quite unable to do that, much of the time.

I have tried to be honest myself, but often it is very hard to be honest if one fears that honesty will cause pain to the other or loss to oneself. Of the many lovers I have had, I remain in regular communication with twelve of them, and as close friends I would say with seven, as well as with a number of others with whom I have never had a sexual love affair.

Some lovers have broken off from me, probably in pain, refusing to communicate with me again, and most often without ever really telling me why they did it. I believe it has usually been over issues of jealousy and possession.

They have not reproached me with being unkind, thoughtless, inattentive, or dishonest to them. If they were bothered or angry, it was not with who I was when I was with them or even that I was not with them as they wanted me to be. They were bothered about what my relationship with other women might be when I was not with them, or that they could not have with me the relationship they desired, living together, being married, or having children with me.

It seems to me a testimony to the intensity of my fidelity and loyalty, that I would not agree to turn away from those I had loved before and be possessed by one new person alone; that has been an obstacle to some women who loved me most and whom I in turn loved deeply.

In an existential journey from the ideal of Catholic marriage to the principle of free love, I came to believe that I would not consent to be exclusively possessed in love by any person; I would not form my primary love relationship with any woman who could not accept this. Thus it has been that my most enduring primary love relationships, with my second wife and with my present companion, have been with women who accepted this in me, and remain my two closest friends.

I regret that I cannot name other women I have loved so much. Something in me wants to use the names by which I know them, but I cannot do this in faithfulness to them, because too often some have made clear to me that they wanted confidentiality.

If I name people here with a first name and a surname (other than my first wife, Jean, who has died), they have consented to be named. If I name them only with a first name, it is a pseudonym used for the fluency of the narrative, but concealing their identity.

A few more words in general about the psychology of loving and the arithmetic of loving: sexual relations are not the highest form of intimacy, although I have found that they have always intensified the bond of loving for me.

Still, it can be quite easy to have sex without intimacy. I have tried sex with prostitutes on a number of occasions. I have always treated them with the respect and affection that is due to people practicing a profession that is so often demeaning and so widely despised. However, it is always quite unsatisfactory, because the mutuality of desire and loving are not present.

The highest form of intimacy is the open communication of honest friendship, if we finally dare to tell another person who we really are, and, even, almost understand the soul of the other. That is far more difficult and more rare than the pleasure of loving sexual relationships.

The great love of your life is not the one with whom you have sex, but the one with whom you finally dare to talk and tell the truth about yourself.

In the psychology of the human, it is seldom possible to find all forms of satisfaction and fulfillment in the love of one person. I don't understand why in loving we should even attempt to find one person who would meet all our complex emotional needs, while at the same time we meet all of theirs. We don't expect this in any other form of friendship.

Finally, the arithmetic of loving – the design of nature is such that in every community of a thousand births, about half are women, about half are men. But the actuarial fact of differentials in death rates, homosexual inclinations and vocations to abstinence or celibacy, leave us always uncertain as to how many women may be seeking heterosexual pairings, and how many men are seeking the same. Let us say that in some theoretical sample of one thousand, there are four hundred women wanting pairings with four hundred willing men.

Let us say that after much seeking and thrashing around in the dark, there emerges the improbable total of three hundred and fifty reasonably happy and reasonably stable monogamous pairings. That leaves fifty still seeking among fifty possible partners.

The problem is that the most attractive and the easiest to please are already paired with one another, while the most difficult to please and the least able to please are still left seeking the perfect pairing with another.

If we had an ethic of loving that allowed or encouraged each person to have two love partners, or even three, there would then be twelve hundred possible pairings among the four hundred women and four hundred men and each person would have three times the chance of finding at least one other person to love, and be loved by.

I believe that our refusal to share our lovers with others springs from the same spirit of possessiveness and greed that leads one person with money to live alone in a ten room house, while others with nothing live homeless on the streets; or one person with money lays claim to thousands or even millions of acres of land, that Earth and nature created over the course of billions of years, while the disinherited of Earth have no land even to feed their families.

Finally, let me say that in the evolution of my own ethic of love in the mid 70s, I was helped by reading several books:

Rollo May - Paulus is a humanistic psychologist's memoir on the issue of love in the life of his friend, the famous Protestant theologian, Paul Tillich.

Hannah Tillich - From Time to Time is the autobiography of Paul Tillich's wife, Hannah.

Simone de Beauvoir - biographies of the author of The Second Sex, who was a lover of Jean Paul Sartre and Nelson Algren, among others.

Emma Goldman - Living My Life, two volume autobiography of a famous turn of the 19th Century anarchist and advocate of free love.