A LONG WALK FOR ENDING THE

DEATH PENALTY IN ILLINOIS

The State Legislature abolished the death penalty that year, except for treason, or murdering a police officer or prison guard. It was reinstated in 1977, and finally abolished in full in 2011.

"We Strangers and Afraid"

May 1965, Catholic Worker

I went to my first meeting of the Illinois Committee to Abolish Capital Punishment. I sat and listened. Near the end, Father James Jones (Episcopal), the chairman, suddenly asked me to contact a state representative who was totally unknown to me. I was startled. I said, “Why me? Why has lightning suddenly struck here?” He replied, “Someone has to reach these people. You know, you can’t walk to Moscow on this issue.” What was his surprise to read in the papers a few days later that I had set out on a two-hundred-sixty-mile walk to the state capital at Springfield to contact thousands of people I did not know.

“Convert your time to something that is constructive and don’t interfere with God’s laws or you may get the long end of the stick. We need the death penalty to make wicked men and women know they can’t play around with sin and not pay.” So wrote a man who saw my picture in the paper when I set out.

“We shoot rats and think nothing of it; the death penalty still has its place,” said a priest in Herscher, Illinois through a screen door, while he left me standing in pouring rain.

In the open spaces of the Illinois prairie, I found out why the death penalty still stands.People fear the stranger and have closed their hearts to his sufferings.

People waved and tooted their horns, signifying that they had seen me on TV or read about me in the papers; they stopped along the highway to satisfy their curiosity about my one-man project, but they didn’t offer help or hospitality.

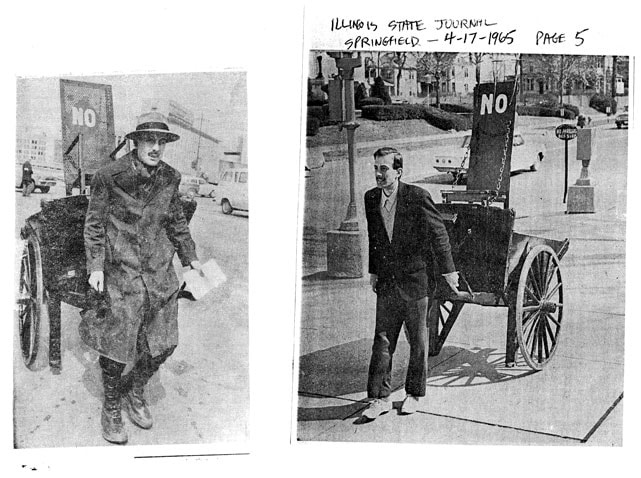

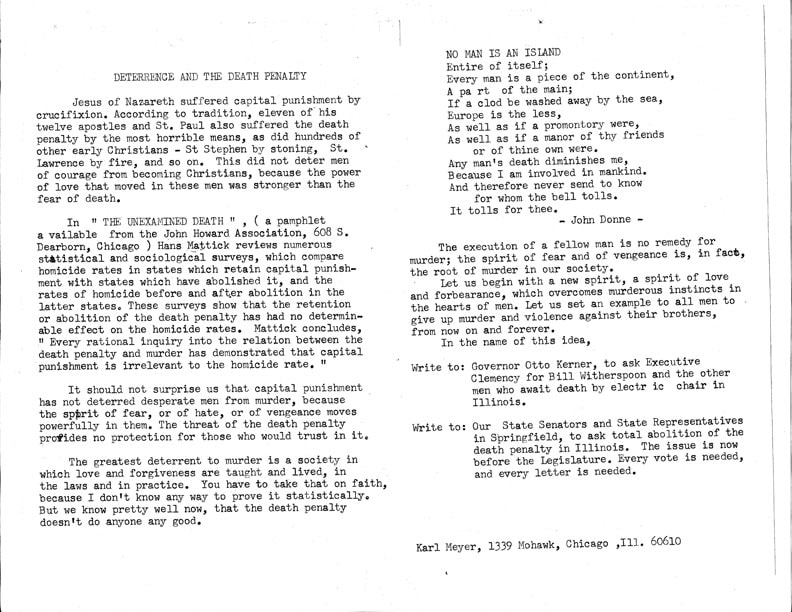

I was alternatively pushing or pulling a heavy two-wheeled cart, containing a washtub full of literature and my personal belongings. People passed me in their cars and trucks on the way to their homes. Miles and hours later, they watched me toiling across the prairie toward their houses, then passing, then toiling away from them, sometimes in rain, battling strong winds from the southwest, with dusk falling, sometimes in darkness, until I disappeared across the southern horizon. And yet, no man, in all the farm country from Chicago to Springfield, came out to say, “Friend, you look tired and hungry; come in and rest awhile and have a bite to eat.”

In Herscher, the Lowells have a rooming house. After talking with me a while and weighting the matter gravely, they agreed to take me in, and then proved very kind and open-hearted. They showed me their collection of rocks from all over the world, and replicas of the American flag, made with thousands of sea shells. In the morning I offered my rent to Mrs. Lowell. “Two dollars,” she said. I paid her. “Now,” she said, “I am going to turn round and donate this to your cause,” and so she did.

After fighting southwest winds all day and making only fourteen miles beyond Herscher, I came to a junction, around 6 p.m. A alrge weatherbeaten billboard pointed to: KEMPTON—A LITTLE TOWN WITH A BIG HEART. John Kearney, in Chicago, had given me the name of a liberal minister in Kempton. I had not gone a quarter mile when a deputy sherrif pulled up to inquire about my mission in the town.

The minister had moved from the town some months before, but the deputy agreed to take me to another Christian minister. He left me in the car while they talked for a long time. Then they came out and very cordially told me about a hotel in the town of Chatsworth, twenty miles away. The deputy drove me back to the junction. I unlocked my cart under the lengthening shadow of the billboard, and continued my journey. The wind had died. Thirteen miles and four hours brought me to the town of Piper City.

A truckload of youths came out to watch me arrive, and they took literature. The town policeman appeared and also recommended the hotel in Chatsworth. I left my cart and hitchhiked to Chatsworth. The next morning, I walked back six miles because I was unable to hitch a ride.

Toward afternoon, I lay down by the roadside to take a nap. A young farmer drove out with a jar of ice water, and would have taken me home for a meal, but I had just eaten.

Beyond this town there were no hotels, and I went on walking through the night, sleeping a few hours by the roadside, and making fifty-two miles, from Piper City to Champaign-Urbana, in two days.

I kept to the side roads and county roads to avoid the heavy traffic on the major two-lane highways to Springfield. There is something on the prairie, which the road maps describe as “improved roads.” I was glad to see that one of the side roads out of Decatur was an “improved road” to Mount Auburn. I took it.

Certainly, if one tried to cross the ploughed fields of southern Illinois in April, dragging a two-wheel cart, one would soon bog down to the axles. From this point of view, it would surely be true that a thin layer of gravel with some tar poured over it would be an improvement, as a roadway, over the natural condition of the prairie. In this sense, I was on an improved. I walked all day through heavy raid and them mud oozing out of the cracks in the improved road.

Darkness had fallen when I struggled up Mount Auburn into the town. (One learns that the prairie is not flat as formerly seen and believed.) Inquiries in a tavern disclosed that there were no hotels or rooming houses. Light poured through stained-glass images from the life of Christ, at a church on a hill, where evening services for Wednesday in Holy Week were about to begin.

I entered the church, identified myself and the purpose of my pilgrimage, and asked for a night’s lodging. The pastor talked it over with members of his congregation. During the service, we sang the moving hymns remembered from childhood. Afterwards, the pastor said that no one had room, but offered to drive me to a motel in Illiopolis, eight miles distant.

Two men of the congregation had agreed to ride along. One had seen me on TV. They were big strapping men, and the pastor wanted me to ride in the front seat. I can only conclude that he was afraid of me, afraid that I might prove to be a criminal or a lunatic. These contingencies provided for, he was most charitable and offered to pay the motel bill.

Fear that the stranger is a criminal, and the belief that the criminal is completely strange to us—these were the attitudes against which I struggled.

The next day I went on, but the west wind was strong against me. Near Rochester, seven miles short of Springfield, the wind came up so strong that I could go no further. I left the cart and took refuge in an empty stone house by the roadside. I lay down and rested for several hours in a pile of straw. Darkness had come when I left the house and hitched into Springfield for a good night’s sleep. But many eyes had watched me enter the stone house.

In the morning, when I returned, I found a brown bag by the cart, with the word FOOD printed on it. In it were an orange and two rolls. A boy of about twelve rode out on a bicycle to talk with me. It was he who had left the food for my breakfast. His name was Kris Hasselbring. He thought I had spent the night in the stone house. He knew nothing of me or my mission, but perhaps he was too young and too small to be afraid of his fellow man.

The day was Good Friday. I fashioned three crosses from sticks to mount on my sign, which was a replica of the electric chair, with the one word NO on face and back—three crosses to commemorate three criminals who suffered capital punishment on this day, many years ago, according to tradition. So I arrived in Springfield and rolled up to the steps of the State Capitol.

In Springfield, I went to visit the Rev. Richard Graebel of First Presbyterian Church. I said, “I am the man who just walked from Chicago to Springfield for the abolition of capital punishment.” He replied, with a laugh, “You look as though you have been punished enough for that,” and helped me to find a parking place for my cart until I can bring to back by trailer to Chicago.

I have written of farmers and country people and not of the people in the cities where I stopped: Chicago and suburbs, Kankakee, Champaign-Urbana, Decatur, and Springfield. I spent half of my time in these cities visiting people and talking abolition. Catholic Worker readers looked for me and did not find me. Liberals took me into their homes and rescued me from the portent of tornadoes (though I for my part stood ready to carry my campaign to Oz).

Clergyman of many faiths agreed to work for abolition of the death penalty. The press received me with open pages. In Champaign, the cops tried to tun me off with threats of arrest for leafletting, but Iran them off to their City Attorney with talk of civil rights and civil liberties, refusing to be intimidated. But all this was expected, because I was not “the stranger” to these people.

Perhaps it is because killers and lawbreakers are no strangers to me that I am still begging the people of Illinois to get in touch with their State Senators and urge total abolition of the death penalty.

The abolition bills come to a vote in the Judiciary Committee on May 4th, and some time after that will come the decisive vote on the floor.