Hospitality For People In Need

In 1958, at the age of twenty-one, just after graduating from the University of Chicago, I began offering housing to homeless men, in a community affiliated with the Catholic Worker movement. There are now more than two-hundred such communities, urban houses and rural farms, around the United States and several other countries. See: www.catholicworker.org for a directory, and more information.

What Is To Be Done?

I came home from work this evening firmly determined to excommunicate from St. Stephen’s House of Hospitality (to cut off from all communication with) one of those men who was among the first to come to us, an alcoholic, who has been with us on and off, mostly on, for over three years. Not to cut him off because it is the Christian thing to do, or the Catholic thing, or the redemptive thing, or the kind thing, but because it is a thing that must be done. It must be done because he hasn’t gotten any better over the years with us. He has in fact gotten much worse. He used to be amiable and pleasant, now he is bitter and often belligerent. He used to have some physical resilience; now he is groggy and confused. He was never sober enough to know the meaning of consideration for others, but he used to listen when you asked him to do a considerate thing. He used to have more control over the bladder when he slept on other people’s beds without asking them, and sometimes he even took off his shoes.

It must be done because I haven’t gotten any better over the years with him. In fact, I’ve gotten worse. I used to be gentle, sort of sentimental; now I’ve gotten hard-nosed. I used to be patient (my friends will laugh), but I haven’t much patience any more. And then, I used to sleep in the back room where I couldn’t hear him knocking on the front door at three a.m. which he always did, and the other people had to get up and let him in, or curse him and argue with him until he agreed to go away, which he used to do sometimes.

No, it must be done because he’ll never go away and stay away until he knows that he doesn’t have a chance here. Give him an inch, and he’ll take a mile or two, and I don’t have it to give any more. Give him a cup of water and he’ll take the kitchen sink, and the rest of us have to wash our hands there, and our shirts and our dishes, because it’s the only sink we’ve got.

So I came home from work this evening, and there was a letter from Jim Forest, asking me to write about Houses of Hospitality and why there should be more of them and what they should be like and how you start one. So I have to take time away from other things and people and write quickly what I know.

In his book, What Is To Be Done?, Leo Tolstoy tells of taking the census of a slum district in Moscow, and of the comprehensive institutions and plans he envisioned for eliminating destitution in the city. While he was planning, his old friend Sutaief came to his house for a visit:

He sat immovable, dressed in his black-tanned sheepskin coat, which he, like other peasants, wore indoors as well as out. It seemed that he was not listening to us, but was thinking about something else. His small eyes gave no responding gleam, but seemed to be turned inward. Having spoken out to my satisfaction, I turned to him and asked him what he thought about it.

“The whole thing is superficial,” he replied.

“Why?”

“The plan is an empty one and no good will come of it,” he repeated with conviction.

“How is it that nothing will come of it? Why is it a useless business, if we help thousands, or even hundreds, of unhappy ones? Is it a bad thing, according to the gospel, to clothe the naked, or to feed the hungry?

“I know, I know; but what you are doing is not that: Is it possible to help thus? You are walking in the street; somebody asks you for a few kopeks; you give it to him. Is that charity? Do him some spiritual good: teach him— What you gave him merely says, ‘Leave me alone.’”

“No; but that is not what we were speaking of: we wish to become acquainted with the wants, and then help by money and deeds. We will try to find for the poor people some work to do.”

“That would be no way of helping them.”

“How then? Must they be left to die of starvation and cold?”

“Why left to die? How many are there of them?

“How many?” said I, thinking that he took the matter so lightly from not knowing the great number of these men. “You are not aware, I dare say, that there are in Moscow about twenty thousand cold and hungry. And then think of those in St. Petersburg and other towns!”

He smiled. “Twenty thousand! And how many families are there in Russia alone? Would they amount to a million?”

“What of that?” said he, with animation, and his eyes sparkled. “Let us unite them with ourselves; I am not rich myself, but will at once take two of them. You take a young fellow into your kitchen; I invite him into my family. If there were ten times as many, we should take them all into our families. You one, I another. We shall work together; those I take to live with me will see how I work; I will teach them to reap, and we shall eat out of one bowl, at one table; and they will hear a good word from me, and from you also. This is charity; but all this plan of yours is no good.”

These plain words made an impression on me. I could not help recognizing that this was true, but it seemed to me then, that, notwithstanding the justice of what he said, my proposed plan might, perhaps, also be useful.

But the longer I was occupied with this affair, and the closer my intercourse with the poor, the oftener I recollected these words, and the greater meaning I found in them.

I indeed go in an expensive fur coat, or drive in my own carriage, to a man who is in want of boots: he sees my house which casts two hundred rubles a month, or he notices that I give away, without thinking, five rubles, only because such is my fancy; he is then aware that, if I give away rubles in such a manner, it is because I have accumulated so many of them that I have a lot to spare, which I not only am never in the habit of giving to anyone, but which I have, without compunction, taken away from others. What can he see in me but one of those persons who have become possessed of what should belong to him?

I have my own Sutaief in Lemont who has been with me longer even than the alcoholic whom I mentioned above. I would not have you believe that all who come to a House of Hospitality are a burden. Quite as many are a source of joy and strength. There are good men and kind men and gentle, poets and wise men, scholars and philhosophers.

Lemont as long hair and a long beard and wears his black coat and gloves in the house and washes less than most, so that the respectable suppose that he is very strange and alien. But he is more kind and wise and scholarly than all the bourgeois I know. He loves the passage from Tolstoy, and he always counsels me not to try to do too much for too many, because just as we must all bear one another’s burdens, so too any one of us can only bear the burdens of a few. But there are so few of us here and the needs of the poor press upon us overwhelmingly, so that “never to be safe again is all our lives.”

It isn’t that the man I must excommunicate could not be helped, but that behind him stand ten thousand more, and I cannot take them all, starting with him. If you open the door they will come in by hundreds; I have seen them with my own eyes. At one time we fed eighty men a night in a kitchen ten feet by ten feet. The first thing is to survive, the first year and the second and the third. If you don’t survive yourself, you can’t do anything for anyone. There have been Houses of Hospitality where the householders drove themselves to insanity. Lesson Number One: Do not burden yourself beyond the limit of grace, humanity, and survival.

We need more Houses of Hospitality where the strong will share the burdens of the weak. The more houses the better, because the more there are, the lighter will be the burdens in each house, and the lighter the burdens, the more the weak will be strengthened to walk. I am not saying that you should take alcoholics and psychotics into your house, because few can bear it or know what to do, but I am speaking of the sick and old and unemployed and orphans (so many of the alcoholics and psychotics were raised in orphanages).

I mentioned that I come home from work in the evening. Why am I not home all day? I come home from work in the evening because I work all day to earn a living for my household. Dorothy and my good priest [Daniel Berrigan, SJ] often tell me I should quit work and beg for our living, so that I could do more for the poor. But if I did more for the poor by begging money from people, the people would do less for the poor by paying me to do a bad job for them. You can have a real estate broker and an insurance broker, but you can’t have a broker for your charity. If people gave me money they would not be able to take the poor into their own homes, nor would they be able to ask their boss for a reduction in salary so that the low-paid workers in their hospital or restaurant or business could be paid more, nor would they be able to go into a high-class restaurant and offer to pay double the check so that the fifty-cents-an-hour dishwasher could be paid a decent wage, nor would they be able to cut their pay in half so that the unemployed could be hired to share the piled-up work that puts such pressures on the employed and often breaks up homes and ruins lives. I have to fight with my employer to keep from doing overtime and getting home even later in the evening. I tell him, “There are thousands unemployed. Go out and hire them to do overtime.”

Yes, if people were to give me money, we would have one big House of Hospitality in every major city, and one hundred would be inside and ten thousand would be outside, and the people would say “We have a House of Hospitality in our city. Let the poor get themselves over there before it closes at eight p.m.”

Now I hope no one will say, “Well, I was going to send you a dime, but I see you don’t want my money so I’ll go out and get an ice cream cone instead.” In that case I’ll take the dime, but it isn’t the better way.

So that is why we need Houses of Hospitality, and why I work and have a small House of Hospitality.

Now when and how do you start a House of Hospitality and what is it like?

I started my first Catholic Worker house in Washington, D.C., when I was nineteen years old and not even a Catholic. I was working as a messenger for Dean Acheson’s law firm, one of the biggest, and most of our work was defending giant corporations in anti-trust suits. Not every anarchist starts out by being perfectly consistent.

I rented a store on the roughest street in the roughest neighborhood in town, on O St. between Sixth and Seventh, though I didn’t know about it at the time. It was just where I happened to get a store. There were more murders around there than in any other precinct. I was the only white man in the block, and when I came home from meetings late at night the police used to stop me and warn me to get out of the neighborhood. My father wasn’t in Congress yet; my parents were home in Vermont and my mother never really knew.

The store had a middle-sized front room with a show window, a very small kitchen with a sink, and in the back, a larger room with no windows and a small alcove with a toilet. The floor was of concrete, and water used to come in and stand around in various spots in the back room. For this I paid fifty dollars a month, cash on the barrelhead, and I had not a grain of trouble renting it in spite of my age, its location, and the strange purposes I proposed for it. I bought a stove, refrigerator and a gas heater in successive months.

Instead of getting beds and chairs, I got fifty dollars worth of lumber and constructed six benches to do double duty service for sleeping in the back room and meetings in the front room. The neighbors, and also some cops, came in to see what all the hammering was about, and they wanted to know what kind of racket I was setting up, but I didn’t say much. Some of them wanted to buy the benches then and there. I should have sold them. I had everything set up and was ready to receive my guests. But I sat there and sat there and nobody came. I started in June and for several months nobody came. Summer passed. In early autumn I was walking along the street and I saw a man lying on the steps of a Protestant church. I wakened him with difficulty; he was loaded. I loaded him into a cab and brought him home. I was exultant.

In the Catholic Worker of January 1962, I wrote of my exultation after my first venture in alley picking. It could not have compared with my joy in my first action of hospitality. But within three days my joy was to turn to desperation. My new guest was stone drunk, and if I had known anything about it, I would have observed that he was absolutely punchy from years of drunkenness. But immediately determined upon his redemption from wine. I put him to bed, or rather to bench. For the next two days I tried to sober him up, but what was my despair to discover that in the morning he was as drunk as the night before. Somehow he managed to elude me and to oil himself up frequently. I didn’t get much sleep because he didn’t seem to keep regular hours. All he could eat was sugar with coffee. By the morning of the third day I was exhausted and desperate.

I called my friend Jim Guinan of Friendship House (who was to become my godfather at my baptism a few months later) and he told me to bring him over. As soon as the poor man was delivered into Jim’s old hands, I went upstairs, lay down on a couch and cried for half an hour. After that I was all right. I had learned a lesson—Lesson Number Two: Don’t demand prompt success from anyone else, or from yourself. After five months of operations and one three-day guest, I closed my first House of Hospitality. I would only mention that Jack Biddle drove me home once with Ammon Hennacy from a meeting where Ammon spoke, and they stopped and had a look at my place when they dropped me off. That was before Ammon knew me at all, but perhaps he remembers that house.

After all this I went to New York and, the following June, joined the people of the Catholic Worker in their Civil Defense protest, and served my first thirty days in jail.

A year later, Ed Morin and I started St. Stephen’s House (I got the store and he got the people), which has met with some success in its almost four years. I have written all of this preface so that you might say, “If such a fool as this can do it, perhaps I can too.”

As my Washington experience illustrates, setting up house is easy: it’s the hospitality that brings problems.

St. Stephen’s House is located with a view to the major relevant factors. I am poor and I am taking the poor into my house, so we are going to be even poorer. Therefore, we are set on the edge of a small slum pocket, a back pocket, just three blocks away from Chicago’s glittering Gold Coast. We are in a poor neighborhood because slum landlords are tolerant of poverty, slum tenants are tolerant of poverty, and police and building department officials are tolerant of poverty, in poor neighborhoods; we get along well with our neighbors. It is no crime to be poor here. Some houses have had to move time and again because they kept moving into places where it was a crime to be poor.

Furnishings and food we get from the Gold Coast alleys. Fortunately, it evidently is not a crime to salvage the criminal wastes of these rich neighbors. They think us quaint, seeing us going about at late hours poking our heads in garbage pails or dragging bed springs through back streets.

We live in a store. On account of the marginal nature of small business in the slums, storefront properties offer more space for less rent than regular housing units. We have five rooms with steam heat for seventy dollars a month. The steam comes once a day, if it comes at all, but the kitchen oven warms the whole house. There are four floors of tenement flats above, and at least once a month the plumbing breaks down above us and water pours from floor to floor on its way to the sea, but I haven’t met a pipe I couldn’t plug. In between the floods we are warm and dry and life is pleasant here.

In ten months of 1960 (I was in jail for two months) my expenses for the house ranged from $131.28 to $347.97. The basic monthly costs were approximately as follows:

Rent…………. $70

Gas………….. $10

Electricity…… $10

Phone……….. $8

Laundry……… $12

Food…………. $40

Total: $150

Miscellaneous costs include the following:

Raincoats for an American Friends Service Committee peace vigil $18.48

Payment of a fine and costs to spring Ed Boudin from the city jail $29.00

Leaflets for the protest in behalf of Eroseanna Robinson $15.00

Travel to and from peace conferences and meetings $48.74

There were ten beds in the house, always taken, and occasionally extra people would sleep on the floor for several days, or even several weeks.

Around six or eight men came from outside each night for supper.

We had clothing for those who needed it, and bread for some of the families in our building.

Three of the men in the house lived here through the entire year, and I was able to claim them as dependents for non-tax purposes.

The meals were cooked and the house was kept by Joe Patrofsky, who worked seven days a week, because he was a working man “too old to work” and the work was there and who else did it, and all he got for it was sixty minutes an hour, as Richard says when he mops the floor. I realize now that we exploited him by not giving him more help, and my only excuse is that I worked as hard myself, though I took a day off whenever I pleased.

Well, what of these people to whom we offer hospitality? They are of every shape and sort, and every state of poverty and destitution. Three may be old or sick and “unemployable;” two may have mental illness or psychosis; one may be an alcoholic, or a wandering man of God, an indigent student or an unpaid peace worker, or simply an unemployed worker. We have had here a journalist, of the Jewish faith he always made clear, who was unemployed because the FBI kept going around and telling his employers that he had twice refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee about his activities in behalf of integration in the South. We have had here a poor rich young man who was doing alternative service as an orderly in a Catholic hospital and trying to meet the payments on a small sports car. We have had here a generous, kindly, handsome, strong, hardworking young gentleman, who happened to be a Negro, and who didn’t just happen to be employed except for occasional work as a porter in a cheap drugstore, and who happened to wind up in a penitentiary for attempting armed postal robbery. We have had connected with us Mr. Cable, a madman whose behavior was shocking by his own account. We have had here an inferior decorator, of checks that is; he didn’t make a good living by it. There are only two of us who don’t eat meat, but we managed at one time to keep two butchers unemployed. One of them has died now, but the other is still unemployed.

There are workers and scholars and non-workers and non-scholars. If a house is small and the people are different and individual, the strength of one gives help for the weakness of another. The house is a center of thought and action. It is a microcosm of the world. Many visitors come and take away more than they bring. The workers and the non-workers and the non-scholars hear the discussions among the scholars about peace and love and politics and sociology, and they become informed and aware by diffusion. The non-workers and the scholars see the workers at work, but I can’t see that it does them much good.

I believe that a dying man is more alive here, and a living man is more alive still. We have here a community of need, where the first man who comes in need is received, and a community of diversity, where all are welcome. We have a communion between the living and the dying in the natural order, and are often dying unto ourselves in order to live unto others in the supernatural order, but I believe that we become more alive ourselves.

I have walked across the world from Chicago to Moscow, and the scene bored me much of the time. But I am not bored here. We don’t walk past the world and its problems. The world comes in with its problems and sits down for a cup of coffee and a word of consolation.

(Published in TheCatholic Worker - March 1962, and reprinted in a Catholic Worker anthology,

A Penny a Copy, 1995, Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY)

It must be done because I haven’t gotten any better over the years with him. In fact, I’ve gotten worse. I used to be gentle, sort of sentimental; now I’ve gotten hard-nosed. I used to be patient (my friends will laugh), but I haven’t much patience any more. And then, I used to sleep in the back room where I couldn’t hear him knocking on the front door at three a.m. which he always did, and the other people had to get up and let him in, or curse him and argue with him until he agreed to go away, which he used to do sometimes.

No, it must be done because he’ll never go away and stay away until he knows that he doesn’t have a chance here. Give him an inch, and he’ll take a mile or two, and I don’t have it to give any more. Give him a cup of water and he’ll take the kitchen sink, and the rest of us have to wash our hands there, and our shirts and our dishes, because it’s the only sink we’ve got.

So I came home from work this evening, and there was a letter from Jim Forest, asking me to write about Houses of Hospitality and why there should be more of them and what they should be like and how you start one. So I have to take time away from other things and people and write quickly what I know.

In his book, What Is To Be Done?, Leo Tolstoy tells of taking the census of a slum district in Moscow, and of the comprehensive institutions and plans he envisioned for eliminating destitution in the city. While he was planning, his old friend Sutaief came to his house for a visit:

He sat immovable, dressed in his black-tanned sheepskin coat, which he, like other peasants, wore indoors as well as out. It seemed that he was not listening to us, but was thinking about something else. His small eyes gave no responding gleam, but seemed to be turned inward. Having spoken out to my satisfaction, I turned to him and asked him what he thought about it.

“The whole thing is superficial,” he replied.

“Why?”

“The plan is an empty one and no good will come of it,” he repeated with conviction.

“How is it that nothing will come of it? Why is it a useless business, if we help thousands, or even hundreds, of unhappy ones? Is it a bad thing, according to the gospel, to clothe the naked, or to feed the hungry?

“I know, I know; but what you are doing is not that: Is it possible to help thus? You are walking in the street; somebody asks you for a few kopeks; you give it to him. Is that charity? Do him some spiritual good: teach him— What you gave him merely says, ‘Leave me alone.’”

“No; but that is not what we were speaking of: we wish to become acquainted with the wants, and then help by money and deeds. We will try to find for the poor people some work to do.”

“That would be no way of helping them.”

“How then? Must they be left to die of starvation and cold?”

“Why left to die? How many are there of them?

“How many?” said I, thinking that he took the matter so lightly from not knowing the great number of these men. “You are not aware, I dare say, that there are in Moscow about twenty thousand cold and hungry. And then think of those in St. Petersburg and other towns!”

He smiled. “Twenty thousand! And how many families are there in Russia alone? Would they amount to a million?”

“What of that?” said he, with animation, and his eyes sparkled. “Let us unite them with ourselves; I am not rich myself, but will at once take two of them. You take a young fellow into your kitchen; I invite him into my family. If there were ten times as many, we should take them all into our families. You one, I another. We shall work together; those I take to live with me will see how I work; I will teach them to reap, and we shall eat out of one bowl, at one table; and they will hear a good word from me, and from you also. This is charity; but all this plan of yours is no good.”

These plain words made an impression on me. I could not help recognizing that this was true, but it seemed to me then, that, notwithstanding the justice of what he said, my proposed plan might, perhaps, also be useful.

But the longer I was occupied with this affair, and the closer my intercourse with the poor, the oftener I recollected these words, and the greater meaning I found in them.

I indeed go in an expensive fur coat, or drive in my own carriage, to a man who is in want of boots: he sees my house which casts two hundred rubles a month, or he notices that I give away, without thinking, five rubles, only because such is my fancy; he is then aware that, if I give away rubles in such a manner, it is because I have accumulated so many of them that I have a lot to spare, which I not only am never in the habit of giving to anyone, but which I have, without compunction, taken away from others. What can he see in me but one of those persons who have become possessed of what should belong to him?

I have my own Sutaief in Lemont who has been with me longer even than the alcoholic whom I mentioned above. I would not have you believe that all who come to a House of Hospitality are a burden. Quite as many are a source of joy and strength. There are good men and kind men and gentle, poets and wise men, scholars and philhosophers.

Lemont as long hair and a long beard and wears his black coat and gloves in the house and washes less than most, so that the respectable suppose that he is very strange and alien. But he is more kind and wise and scholarly than all the bourgeois I know. He loves the passage from Tolstoy, and he always counsels me not to try to do too much for too many, because just as we must all bear one another’s burdens, so too any one of us can only bear the burdens of a few. But there are so few of us here and the needs of the poor press upon us overwhelmingly, so that “never to be safe again is all our lives.”

It isn’t that the man I must excommunicate could not be helped, but that behind him stand ten thousand more, and I cannot take them all, starting with him. If you open the door they will come in by hundreds; I have seen them with my own eyes. At one time we fed eighty men a night in a kitchen ten feet by ten feet. The first thing is to survive, the first year and the second and the third. If you don’t survive yourself, you can’t do anything for anyone. There have been Houses of Hospitality where the householders drove themselves to insanity. Lesson Number One: Do not burden yourself beyond the limit of grace, humanity, and survival.

We need more Houses of Hospitality where the strong will share the burdens of the weak. The more houses the better, because the more there are, the lighter will be the burdens in each house, and the lighter the burdens, the more the weak will be strengthened to walk. I am not saying that you should take alcoholics and psychotics into your house, because few can bear it or know what to do, but I am speaking of the sick and old and unemployed and orphans (so many of the alcoholics and psychotics were raised in orphanages).

I mentioned that I come home from work in the evening. Why am I not home all day? I come home from work in the evening because I work all day to earn a living for my household. Dorothy and my good priest [Daniel Berrigan, SJ] often tell me I should quit work and beg for our living, so that I could do more for the poor. But if I did more for the poor by begging money from people, the people would do less for the poor by paying me to do a bad job for them. You can have a real estate broker and an insurance broker, but you can’t have a broker for your charity. If people gave me money they would not be able to take the poor into their own homes, nor would they be able to ask their boss for a reduction in salary so that the low-paid workers in their hospital or restaurant or business could be paid more, nor would they be able to go into a high-class restaurant and offer to pay double the check so that the fifty-cents-an-hour dishwasher could be paid a decent wage, nor would they be able to cut their pay in half so that the unemployed could be hired to share the piled-up work that puts such pressures on the employed and often breaks up homes and ruins lives. I have to fight with my employer to keep from doing overtime and getting home even later in the evening. I tell him, “There are thousands unemployed. Go out and hire them to do overtime.”

Yes, if people were to give me money, we would have one big House of Hospitality in every major city, and one hundred would be inside and ten thousand would be outside, and the people would say “We have a House of Hospitality in our city. Let the poor get themselves over there before it closes at eight p.m.”

Now I hope no one will say, “Well, I was going to send you a dime, but I see you don’t want my money so I’ll go out and get an ice cream cone instead.” In that case I’ll take the dime, but it isn’t the better way.

So that is why we need Houses of Hospitality, and why I work and have a small House of Hospitality.

Now when and how do you start a House of Hospitality and what is it like?

I started my first Catholic Worker house in Washington, D.C., when I was nineteen years old and not even a Catholic. I was working as a messenger for Dean Acheson’s law firm, one of the biggest, and most of our work was defending giant corporations in anti-trust suits. Not every anarchist starts out by being perfectly consistent.

I rented a store on the roughest street in the roughest neighborhood in town, on O St. between Sixth and Seventh, though I didn’t know about it at the time. It was just where I happened to get a store. There were more murders around there than in any other precinct. I was the only white man in the block, and when I came home from meetings late at night the police used to stop me and warn me to get out of the neighborhood. My father wasn’t in Congress yet; my parents were home in Vermont and my mother never really knew.

The store had a middle-sized front room with a show window, a very small kitchen with a sink, and in the back, a larger room with no windows and a small alcove with a toilet. The floor was of concrete, and water used to come in and stand around in various spots in the back room. For this I paid fifty dollars a month, cash on the barrelhead, and I had not a grain of trouble renting it in spite of my age, its location, and the strange purposes I proposed for it. I bought a stove, refrigerator and a gas heater in successive months.

Instead of getting beds and chairs, I got fifty dollars worth of lumber and constructed six benches to do double duty service for sleeping in the back room and meetings in the front room. The neighbors, and also some cops, came in to see what all the hammering was about, and they wanted to know what kind of racket I was setting up, but I didn’t say much. Some of them wanted to buy the benches then and there. I should have sold them. I had everything set up and was ready to receive my guests. But I sat there and sat there and nobody came. I started in June and for several months nobody came. Summer passed. In early autumn I was walking along the street and I saw a man lying on the steps of a Protestant church. I wakened him with difficulty; he was loaded. I loaded him into a cab and brought him home. I was exultant.

In the Catholic Worker of January 1962, I wrote of my exultation after my first venture in alley picking. It could not have compared with my joy in my first action of hospitality. But within three days my joy was to turn to desperation. My new guest was stone drunk, and if I had known anything about it, I would have observed that he was absolutely punchy from years of drunkenness. But immediately determined upon his redemption from wine. I put him to bed, or rather to bench. For the next two days I tried to sober him up, but what was my despair to discover that in the morning he was as drunk as the night before. Somehow he managed to elude me and to oil himself up frequently. I didn’t get much sleep because he didn’t seem to keep regular hours. All he could eat was sugar with coffee. By the morning of the third day I was exhausted and desperate.

I called my friend Jim Guinan of Friendship House (who was to become my godfather at my baptism a few months later) and he told me to bring him over. As soon as the poor man was delivered into Jim’s old hands, I went upstairs, lay down on a couch and cried for half an hour. After that I was all right. I had learned a lesson—Lesson Number Two: Don’t demand prompt success from anyone else, or from yourself. After five months of operations and one three-day guest, I closed my first House of Hospitality. I would only mention that Jack Biddle drove me home once with Ammon Hennacy from a meeting where Ammon spoke, and they stopped and had a look at my place when they dropped me off. That was before Ammon knew me at all, but perhaps he remembers that house.

After all this I went to New York and, the following June, joined the people of the Catholic Worker in their Civil Defense protest, and served my first thirty days in jail.

A year later, Ed Morin and I started St. Stephen’s House (I got the store and he got the people), which has met with some success in its almost four years. I have written all of this preface so that you might say, “If such a fool as this can do it, perhaps I can too.”

As my Washington experience illustrates, setting up house is easy: it’s the hospitality that brings problems.

St. Stephen’s House is located with a view to the major relevant factors. I am poor and I am taking the poor into my house, so we are going to be even poorer. Therefore, we are set on the edge of a small slum pocket, a back pocket, just three blocks away from Chicago’s glittering Gold Coast. We are in a poor neighborhood because slum landlords are tolerant of poverty, slum tenants are tolerant of poverty, and police and building department officials are tolerant of poverty, in poor neighborhoods; we get along well with our neighbors. It is no crime to be poor here. Some houses have had to move time and again because they kept moving into places where it was a crime to be poor.

Furnishings and food we get from the Gold Coast alleys. Fortunately, it evidently is not a crime to salvage the criminal wastes of these rich neighbors. They think us quaint, seeing us going about at late hours poking our heads in garbage pails or dragging bed springs through back streets.

We live in a store. On account of the marginal nature of small business in the slums, storefront properties offer more space for less rent than regular housing units. We have five rooms with steam heat for seventy dollars a month. The steam comes once a day, if it comes at all, but the kitchen oven warms the whole house. There are four floors of tenement flats above, and at least once a month the plumbing breaks down above us and water pours from floor to floor on its way to the sea, but I haven’t met a pipe I couldn’t plug. In between the floods we are warm and dry and life is pleasant here.

In ten months of 1960 (I was in jail for two months) my expenses for the house ranged from $131.28 to $347.97. The basic monthly costs were approximately as follows:

Rent…………. $70

Gas………….. $10

Electricity…… $10

Phone……….. $8

Laundry……… $12

Food…………. $40

Total: $150

Miscellaneous costs include the following:

Raincoats for an American Friends Service Committee peace vigil $18.48

Payment of a fine and costs to spring Ed Boudin from the city jail $29.00

Leaflets for the protest in behalf of Eroseanna Robinson $15.00

Travel to and from peace conferences and meetings $48.74

There were ten beds in the house, always taken, and occasionally extra people would sleep on the floor for several days, or even several weeks.

Around six or eight men came from outside each night for supper.

We had clothing for those who needed it, and bread for some of the families in our building.

Three of the men in the house lived here through the entire year, and I was able to claim them as dependents for non-tax purposes.

The meals were cooked and the house was kept by Joe Patrofsky, who worked seven days a week, because he was a working man “too old to work” and the work was there and who else did it, and all he got for it was sixty minutes an hour, as Richard says when he mops the floor. I realize now that we exploited him by not giving him more help, and my only excuse is that I worked as hard myself, though I took a day off whenever I pleased.

Well, what of these people to whom we offer hospitality? They are of every shape and sort, and every state of poverty and destitution. Three may be old or sick and “unemployable;” two may have mental illness or psychosis; one may be an alcoholic, or a wandering man of God, an indigent student or an unpaid peace worker, or simply an unemployed worker. We have had here a journalist, of the Jewish faith he always made clear, who was unemployed because the FBI kept going around and telling his employers that he had twice refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee about his activities in behalf of integration in the South. We have had here a poor rich young man who was doing alternative service as an orderly in a Catholic hospital and trying to meet the payments on a small sports car. We have had here a generous, kindly, handsome, strong, hardworking young gentleman, who happened to be a Negro, and who didn’t just happen to be employed except for occasional work as a porter in a cheap drugstore, and who happened to wind up in a penitentiary for attempting armed postal robbery. We have had connected with us Mr. Cable, a madman whose behavior was shocking by his own account. We have had here an inferior decorator, of checks that is; he didn’t make a good living by it. There are only two of us who don’t eat meat, but we managed at one time to keep two butchers unemployed. One of them has died now, but the other is still unemployed.

There are workers and scholars and non-workers and non-scholars. If a house is small and the people are different and individual, the strength of one gives help for the weakness of another. The house is a center of thought and action. It is a microcosm of the world. Many visitors come and take away more than they bring. The workers and the non-workers and the non-scholars hear the discussions among the scholars about peace and love and politics and sociology, and they become informed and aware by diffusion. The non-workers and the scholars see the workers at work, but I can’t see that it does them much good.

I believe that a dying man is more alive here, and a living man is more alive still. We have here a community of need, where the first man who comes in need is received, and a community of diversity, where all are welcome. We have a communion between the living and the dying in the natural order, and are often dying unto ourselves in order to live unto others in the supernatural order, but I believe that we become more alive ourselves.

I have walked across the world from Chicago to Moscow, and the scene bored me much of the time. But I am not bored here. We don’t walk past the world and its problems. The world comes in with its problems and sits down for a cup of coffee and a word of consolation.

(Published in TheCatholic Worker - March 1962, and reprinted in a Catholic Worker anthology,

A Penny a Copy, 1995, Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY)

Sanctuary

Sanctuary

Catholic Worker

February, 1969

If a person has the money to own an automobile, they gain the right, all over Chicago, to as much as a hundred square feet of public street, wherever they can find it, to park a car. On the other hand, if that person does not have the price of a room for the night, they do not even have the right to lie down on the concrete pavement and claim six square feet of parking space.

To do so would be to commit the crime of loitering or vagrancy. " The foxes have their holes, the birds have their nests, the autos have their parking spaces, but the son of man has nowhere to lay his head."

We live in a society in which every inch of ground is claimed and very tool and means of livelihood is owned as private property. A person, by birth and growing up, does not gain a proportionate share of the land or means of livelihood sufficient to sustain life. One gains it only by the sufferance of those who have come before.

I contend that person, by birth, has at least an unqualified right to the use of enough of the public space to lay their body full length upon the ground and sleep, since, manifestly, they cannot sleep on their feet while in constant motion, nor long survive without some form of rest.

While I am realistic about the prospects for securing fuller economic rights, I think we might take upon ourselves the obligation of securing to every person in Chicago the minimum right of which I speak. As always at this time of year, when I pass people on the street hunched into hooded cotton shirts, I feel an acute renewal of outrage that they haven’t the right to enough ground on which to lie down and freeze.

In times past, and even to the present day, I have maintained various houses of hospitality for the destitute, but never for all of them.

In January 1960, I had my largest storefront, on Division Street, where a pretentious animal hospital now stands, and for a month we took in eighty men a night to eat and to sleep on the floor in rows. They used to lay down newspapers on which to sleep, because the floor was dirty from their feet.

Every morning I had each man fold up his bed and walk in order not to fill our own trash barrel with all the old newspapers. Detectives soon paid us a visit; a neighbor, devoted to “Operation Crimestop,” had called PO-5-1313 to report a storefront where men came out early each morning carrying suspicious looking packages wrapped in old newspapers.

The cops forced us out, because if you are going to provide a residence for human beings, you must have a certain amount of space for each one and conditions befitting the dignity and needs of the human person, or nothing at all. That is why we have always had to close the door and turn men away, because we have never had space for all who would come.

But I have a scheme for a sanctuary where every person and every class of people would be welcome – except for a single group of people, police officers in uniform – where people could come in or out at any time of day or night, to be warm, to rest, to eat, and to find human company. It could not be a residence with rooms and beds, because no one could bear the cost or survive the weight of regulations on such a basis. It would be more like a railroad station than a residence.

In fact, a railroad station would be the most appropriate kind of building. People would walk in and out through revolving doors, without restriction. There would be broad, highbacked benches where guests would sit and rest. If one lay down to sleep between trains to nowhere, no one would disturb them, as long as there was room for others to sit.

There would be a snack bar where a perpetual pot of soup or cereal would boil beside a perpetual urn of coffee and a perpetual loaf of bread. There would be washrooms and shower stalls, with slugs to open the doors, and slug-operated lockers where people could keep their belongings in safety.

It could be a large, unused church building (most churches are unused 99% of the time, but it would be too much to hope that a church that was used 1% of the time would open its doors to the destitute for the rest of the time). In the basement kitchen there would be a perpetual casserole of baked macaroni beside a perpetual urn of coffee and a perpetual one-layer chocolate cake, or even bread and wine in the sanctuary.

An automobile showroom or any other large open building would also serve the purpose.

If a place can be found, I stand ready to do the job, but I could not support it alone, as I have houses of hospitality since 1958. It would need more substantial support from more substantial people. Probably, it would require a donation of the use of a suitable building. Other expenses might be met by a Sunday evening club that would meet at the same place to hear the most eloquent spokesmen of true revolution. That is my scheme on cold nights when men carry the banner on the streets. I am serious, and I would like you to keep your eyes open and let me know what you think.

Sanctuary Part II (Subverting Social Discipline)

Catholic Worker

March-April, 1969

In the February CW, I laid down the details for a universal sanctuary and place of hospitality. Now I wish to discuss the philosophy behind this scheme, the fruit of eleven years of experience in communistic hospitality.

In my blueprint for a universal sanctuary, I have finally declared total and joyful war on “rehabilitation,” that supposed end and purpose of social work, which the well-fed and well-clothed have never ceased to recommend to me in these eleven years.

Who are the persecuted and driven people who would take refuge in such a sanctuary as I described? They are wine drinkers, madmen, crazy ones, and the travelers and tramps of our day, young people, hippies, drifters, radical organizers and resistance workers.

The warm, the dry and the well-fed have never ceased to suggest to me that by keeping these misfits hungry, cold and miserable, or, by a subtler strategy, taking them in, feeding them and warming them, but keeping them insecure and facing them with the prospect of being thrown back out into the cold, we could force them into the labor pool at the lowest level of menial servitude to our economic system and keep them there on a permanent and stable basis, and this we could call “rehabilitation.”

Of course, they have not said it that way in so many words. They have merely suggested that the position of the destitute and our ministry to them gives us the opportunity and the duty to keep upon the destitute a steady and consistent pressure to shape up and adjust themselves to the demands of society.

As war is the extension of diplomacy by other means, hospitality would become the extension of social discipline by other means, and we would be in charge of picking up those who fall by the wayside and getting them back on the treadmill and even putting a rope around their waists, or their necks, and tying them on so that they can go on marching forever, and never fall off again until God takes them unto himself.

I am told that if we provide a free refuge for men who drink large quantities of cheap wine, we only give them the opportunity to waste on wine the money which they would otherwise be forced to spend on food and lodging. If we provide free lodging for the derelict, we merely provide them opportunity to malinger and loaf.

Certainly, it is likewise true that when we pay anyone more than a subsistence wage, we only give them the opportunity to waste on wine or any other luxury all income in excess of what is required to meet the most basic needs. You are warm and well-fed, shall we therefore cease to provide for you more than subsistence wages, because you spend the balance to satisfy your own cravings, even in the face of starvation and suffering around the world?

In a sense our social outcasts are rebels against a particular social and economic order, and a particular kind of social discipline. It is a social order based largely on systematic selfishness (as Peter Maurin said), and in many ways it is profoundly irrational and perverse, as is shown by the billions of dollars which it squanders on military activities, which are self-destructive and destructive of others in a measure infinitely greater than the mere drinking of wine in alleys and back streets.

Under this order, it is only in time of total war that there is full employment and the instant “rehabilitation” of millions who were regarded as unfit to work in happier times. The society, needing them briefly for its own self-destructive binge, must accept them for the time, pretty much as they are.

But under the system of peacetime capitalist competition, there will always be unemployed, moneyless people; and it will always be said that they remain unemployed because they are unfit to work; for, whatever “rehabilitation” they undergo, however much they adjust to competitive demands, there will always be some who are less adjusted, less adaptable, less subservient, less compliant, less conforming than the majority of us, and who will therefore be eternally unfit to serve capitalism. And, because of their unworthiness, the jobs that will be offered to them will be the most menial, the lowest paid, the most unpleasant and the most frustrating, the very jobs which, if we ourselves were required to perform them, might cause us to quit and to join the ranks of the derelict ourselves.

I don’t mean by this to recommend drunkenness or addiction or madness as attractive ways of life. Even setting aside the social tortures, the cold, the hunger, the imprisonment, inflicted by a punitive society, they are in themselves filled with an overflowing measure of misery and pain.

Yet how deadening the ways of life from which even these are a refuge, the vocation of the soldier, the man who must kill, the assembly-line worker, the isolated wage worker without family or friends, the responsible positions filled with unrelievable pressure and frustration.

In a society so irrational and so perverse, we must at least fight for the right of the deviant rebel to drink wine or to be mad. I am even willing to continue in my own economic bondage to capitalism in order to help them in some way to struggle free. I am in that sense the rear guard for an army of liberation, as I am still engaged with the enemy for the protection of the retreating army, those drinkers of wine, those madmen, those impecunious drifters who will not submit to a respectable and reputable life, but keep searching in a confused and hopeless way for something better.

God knows that I get up every weekday morning at 7:00 a.m. I brush my teeth; I wash my face; I shave; I comb my hair. I eat my breakfast, a cup of canned juice and a bowl of cold cereal with nonfat milk. I take my lunch in a brown bag. I kiss my wife and children goodbye at the door, for all the world like Dagwood Bumstead, and catch the “el” for town.

I get to work almost every morning by 9:00, and almost never later than 9:05. Any of my bosses will agree that I am a hard and conscientious worker. I give a full day’s work for a day’s wage, even in those cases of exploitation when the day’s wage isn’t a full day’s wage. And, what is more, I cannot have much visceral respect for anyone who cannot do the same as I.

But I am not ready, like most people, to canonize the pattern of work by which I myself must live; nor am I ready to rehabilitate everyone on pain of starvation to live in the way that I live.

Why do people need “rehabilitation” so desperately? It is because you refuse to give them a tenable place in your society as long as they remain as they are.

I also desire to see people change, to see all people change for the better, whether they be the most powerful and respected people in the society or the most destitute; but I do not believe in making them change by making them miserable. I believe in the example of love at work, not in the discipline of wretchedness.

How I long to see people change so that there may be peace and justice among us, so that we may have a society in which all people can be good. But the big change that must come to all of us is a heart open to the world. We have to accept people as they are, people with attitudes and cultures different from our own, and give them a chance to live.

You may see people who have no money, and you want them to change, to become “rehabilitated.” But rather than changing the people who have no money, I would like to change our evaluation of them. I would like to accept once and for all that people who have no money are equal in worth to those who have much, that they will not be driven from place to place. They will not be treated with scorn and contempt. In one place, in one sanctuary, they will be equal and free from any form of persecution or social blackmail.

Once granting the fundamental right of the deviant to remain so, we need to create a more flexible pattern of economic life, in which the present hard-core unemployed could participate in a way that would respect their individual inclinations, strengths, and frailties.

This means a great diversity of communal and sheltered opportunities for employment. This is better than trying to reshape everyone by discipline to fit the demands of competitive capitalism.

Let us shape the working life to fit people, instead of shaping people to fit the productive mechanism.

In my next article, I will take up this question at greater length.

Catholic Worker

February, 1969

If a person has the money to own an automobile, they gain the right, all over Chicago, to as much as a hundred square feet of public street, wherever they can find it, to park a car. On the other hand, if that person does not have the price of a room for the night, they do not even have the right to lie down on the concrete pavement and claim six square feet of parking space.

To do so would be to commit the crime of loitering or vagrancy. " The foxes have their holes, the birds have their nests, the autos have their parking spaces, but the son of man has nowhere to lay his head."

We live in a society in which every inch of ground is claimed and very tool and means of livelihood is owned as private property. A person, by birth and growing up, does not gain a proportionate share of the land or means of livelihood sufficient to sustain life. One gains it only by the sufferance of those who have come before.

I contend that person, by birth, has at least an unqualified right to the use of enough of the public space to lay their body full length upon the ground and sleep, since, manifestly, they cannot sleep on their feet while in constant motion, nor long survive without some form of rest.

While I am realistic about the prospects for securing fuller economic rights, I think we might take upon ourselves the obligation of securing to every person in Chicago the minimum right of which I speak. As always at this time of year, when I pass people on the street hunched into hooded cotton shirts, I feel an acute renewal of outrage that they haven’t the right to enough ground on which to lie down and freeze.

In times past, and even to the present day, I have maintained various houses of hospitality for the destitute, but never for all of them.

In January 1960, I had my largest storefront, on Division Street, where a pretentious animal hospital now stands, and for a month we took in eighty men a night to eat and to sleep on the floor in rows. They used to lay down newspapers on which to sleep, because the floor was dirty from their feet.

Every morning I had each man fold up his bed and walk in order not to fill our own trash barrel with all the old newspapers. Detectives soon paid us a visit; a neighbor, devoted to “Operation Crimestop,” had called PO-5-1313 to report a storefront where men came out early each morning carrying suspicious looking packages wrapped in old newspapers.

The cops forced us out, because if you are going to provide a residence for human beings, you must have a certain amount of space for each one and conditions befitting the dignity and needs of the human person, or nothing at all. That is why we have always had to close the door and turn men away, because we have never had space for all who would come.

But I have a scheme for a sanctuary where every person and every class of people would be welcome – except for a single group of people, police officers in uniform – where people could come in or out at any time of day or night, to be warm, to rest, to eat, and to find human company. It could not be a residence with rooms and beds, because no one could bear the cost or survive the weight of regulations on such a basis. It would be more like a railroad station than a residence.

In fact, a railroad station would be the most appropriate kind of building. People would walk in and out through revolving doors, without restriction. There would be broad, highbacked benches where guests would sit and rest. If one lay down to sleep between trains to nowhere, no one would disturb them, as long as there was room for others to sit.

There would be a snack bar where a perpetual pot of soup or cereal would boil beside a perpetual urn of coffee and a perpetual loaf of bread. There would be washrooms and shower stalls, with slugs to open the doors, and slug-operated lockers where people could keep their belongings in safety.

It could be a large, unused church building (most churches are unused 99% of the time, but it would be too much to hope that a church that was used 1% of the time would open its doors to the destitute for the rest of the time). In the basement kitchen there would be a perpetual casserole of baked macaroni beside a perpetual urn of coffee and a perpetual one-layer chocolate cake, or even bread and wine in the sanctuary.

An automobile showroom or any other large open building would also serve the purpose.

If a place can be found, I stand ready to do the job, but I could not support it alone, as I have houses of hospitality since 1958. It would need more substantial support from more substantial people. Probably, it would require a donation of the use of a suitable building. Other expenses might be met by a Sunday evening club that would meet at the same place to hear the most eloquent spokesmen of true revolution. That is my scheme on cold nights when men carry the banner on the streets. I am serious, and I would like you to keep your eyes open and let me know what you think.

Sanctuary Part II (Subverting Social Discipline)

Catholic Worker

March-April, 1969

In the February CW, I laid down the details for a universal sanctuary and place of hospitality. Now I wish to discuss the philosophy behind this scheme, the fruit of eleven years of experience in communistic hospitality.

In my blueprint for a universal sanctuary, I have finally declared total and joyful war on “rehabilitation,” that supposed end and purpose of social work, which the well-fed and well-clothed have never ceased to recommend to me in these eleven years.

Who are the persecuted and driven people who would take refuge in such a sanctuary as I described? They are wine drinkers, madmen, crazy ones, and the travelers and tramps of our day, young people, hippies, drifters, radical organizers and resistance workers.

The warm, the dry and the well-fed have never ceased to suggest to me that by keeping these misfits hungry, cold and miserable, or, by a subtler strategy, taking them in, feeding them and warming them, but keeping them insecure and facing them with the prospect of being thrown back out into the cold, we could force them into the labor pool at the lowest level of menial servitude to our economic system and keep them there on a permanent and stable basis, and this we could call “rehabilitation.”

Of course, they have not said it that way in so many words. They have merely suggested that the position of the destitute and our ministry to them gives us the opportunity and the duty to keep upon the destitute a steady and consistent pressure to shape up and adjust themselves to the demands of society.

As war is the extension of diplomacy by other means, hospitality would become the extension of social discipline by other means, and we would be in charge of picking up those who fall by the wayside and getting them back on the treadmill and even putting a rope around their waists, or their necks, and tying them on so that they can go on marching forever, and never fall off again until God takes them unto himself.

I am told that if we provide a free refuge for men who drink large quantities of cheap wine, we only give them the opportunity to waste on wine the money which they would otherwise be forced to spend on food and lodging. If we provide free lodging for the derelict, we merely provide them opportunity to malinger and loaf.

Certainly, it is likewise true that when we pay anyone more than a subsistence wage, we only give them the opportunity to waste on wine or any other luxury all income in excess of what is required to meet the most basic needs. You are warm and well-fed, shall we therefore cease to provide for you more than subsistence wages, because you spend the balance to satisfy your own cravings, even in the face of starvation and suffering around the world?

In a sense our social outcasts are rebels against a particular social and economic order, and a particular kind of social discipline. It is a social order based largely on systematic selfishness (as Peter Maurin said), and in many ways it is profoundly irrational and perverse, as is shown by the billions of dollars which it squanders on military activities, which are self-destructive and destructive of others in a measure infinitely greater than the mere drinking of wine in alleys and back streets.

Under this order, it is only in time of total war that there is full employment and the instant “rehabilitation” of millions who were regarded as unfit to work in happier times. The society, needing them briefly for its own self-destructive binge, must accept them for the time, pretty much as they are.

But under the system of peacetime capitalist competition, there will always be unemployed, moneyless people; and it will always be said that they remain unemployed because they are unfit to work; for, whatever “rehabilitation” they undergo, however much they adjust to competitive demands, there will always be some who are less adjusted, less adaptable, less subservient, less compliant, less conforming than the majority of us, and who will therefore be eternally unfit to serve capitalism. And, because of their unworthiness, the jobs that will be offered to them will be the most menial, the lowest paid, the most unpleasant and the most frustrating, the very jobs which, if we ourselves were required to perform them, might cause us to quit and to join the ranks of the derelict ourselves.

I don’t mean by this to recommend drunkenness or addiction or madness as attractive ways of life. Even setting aside the social tortures, the cold, the hunger, the imprisonment, inflicted by a punitive society, they are in themselves filled with an overflowing measure of misery and pain.

Yet how deadening the ways of life from which even these are a refuge, the vocation of the soldier, the man who must kill, the assembly-line worker, the isolated wage worker without family or friends, the responsible positions filled with unrelievable pressure and frustration.

In a society so irrational and so perverse, we must at least fight for the right of the deviant rebel to drink wine or to be mad. I am even willing to continue in my own economic bondage to capitalism in order to help them in some way to struggle free. I am in that sense the rear guard for an army of liberation, as I am still engaged with the enemy for the protection of the retreating army, those drinkers of wine, those madmen, those impecunious drifters who will not submit to a respectable and reputable life, but keep searching in a confused and hopeless way for something better.

God knows that I get up every weekday morning at 7:00 a.m. I brush my teeth; I wash my face; I shave; I comb my hair. I eat my breakfast, a cup of canned juice and a bowl of cold cereal with nonfat milk. I take my lunch in a brown bag. I kiss my wife and children goodbye at the door, for all the world like Dagwood Bumstead, and catch the “el” for town.

I get to work almost every morning by 9:00, and almost never later than 9:05. Any of my bosses will agree that I am a hard and conscientious worker. I give a full day’s work for a day’s wage, even in those cases of exploitation when the day’s wage isn’t a full day’s wage. And, what is more, I cannot have much visceral respect for anyone who cannot do the same as I.

But I am not ready, like most people, to canonize the pattern of work by which I myself must live; nor am I ready to rehabilitate everyone on pain of starvation to live in the way that I live.

Why do people need “rehabilitation” so desperately? It is because you refuse to give them a tenable place in your society as long as they remain as they are.

I also desire to see people change, to see all people change for the better, whether they be the most powerful and respected people in the society or the most destitute; but I do not believe in making them change by making them miserable. I believe in the example of love at work, not in the discipline of wretchedness.

How I long to see people change so that there may be peace and justice among us, so that we may have a society in which all people can be good. But the big change that must come to all of us is a heart open to the world. We have to accept people as they are, people with attitudes and cultures different from our own, and give them a chance to live.

You may see people who have no money, and you want them to change, to become “rehabilitated.” But rather than changing the people who have no money, I would like to change our evaluation of them. I would like to accept once and for all that people who have no money are equal in worth to those who have much, that they will not be driven from place to place. They will not be treated with scorn and contempt. In one place, in one sanctuary, they will be equal and free from any form of persecution or social blackmail.

Once granting the fundamental right of the deviant to remain so, we need to create a more flexible pattern of economic life, in which the present hard-core unemployed could participate in a way that would respect their individual inclinations, strengths, and frailties.

This means a great diversity of communal and sheltered opportunities for employment. This is better than trying to reshape everyone by discipline to fit the demands of competitive capitalism.

Let us shape the working life to fit people, instead of shaping people to fit the productive mechanism.

In my next article, I will take up this question at greater length.

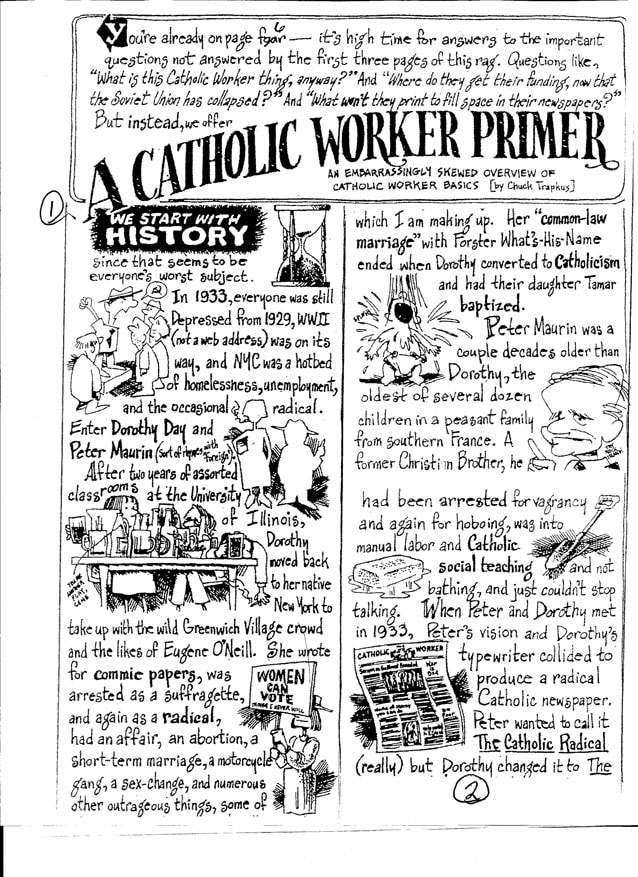

CHUCK TRAPKUS (1959-2000)

Chuck had worked as an editorial cartoonist for a daily newspaper in Rock Island, Illinois. In 1983 he co-founded a Catholic Worker house of hospitality in Rock Island to offer housing for homeless families.

The Catholic Worker Primer below is reprinted from his Catholic Radical newsletter. Chuck was a superb craftsman in the use of hand tools, and a passionate critic of much of modern technology, who traveled mostly by bicycle, so it was especially saddening and paradoxical that he would die prematurely, as a passenger, in an automobile accident in 2000.

The Catholic Worker Primer below is reprinted from his Catholic Radical newsletter. Chuck was a superb craftsman in the use of hand tools, and a passionate critic of much of modern technology, who traveled mostly by bicycle, so it was especially saddening and paradoxical that he would die prematurely, as a passenger, in an automobile accident in 2000.