Saigon Project 1966

Advocating to end the Vietnam War

Working to end the U.S. imperial intervention in the civil war in Vietnam was a major focus in my life from the summer of 1965 through the negotiated U.S. settlement with North Vietnam and the Viet Cong, and the withdrawal of most U.S. forces in 1973.

As an interested student of international affairs, with a particular interest in French history and politics, I first began attending to the Vietnamese war for independence from France in the early 1950s as a teenager.

With the rapid escalation of U.S. intervention in the civil war in South Vietnam in 1964 and 1965, I began working with the Chicago Peace Council coalition and other organizations to oppose U.S. military intervention.

My most significant contributions were ideas, widely published writings, and setting a personal example in developing movements for non-cooperation with the military draft, and refusal to pay federal income and telephone excise taxes that were financing the U.S. intervention. Those actions are documented on the Draft Refusal and War Tax Refusal pages of this website.

As an interested student of international affairs, with a particular interest in French history and politics, I first began attending to the Vietnamese war for independence from France in the early 1950s as a teenager.

With the rapid escalation of U.S. intervention in the civil war in South Vietnam in 1964 and 1965, I began working with the Chicago Peace Council coalition and other organizations to oppose U.S. military intervention.

My most significant contributions were ideas, widely published writings, and setting a personal example in developing movements for non-cooperation with the military draft, and refusal to pay federal income and telephone excise taxes that were financing the U.S. intervention. Those actions are documented on the Draft Refusal and War Tax Refusal pages of this website.

Saigon Project of the Committee for Nonviolent Action -April 1966

In the Spring of 1966, Bradford Lyttle and A.J. Muste conceived a nonviolent action project to send a team of six activists to Saigon to consult with Vietnamese "third way" peace movements, and to carry out a public protest at the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam.

I was invited to be a member of this team, along with Brad, A.J., Dr. William Davidon, a nuclear physicist and Professor of Physics at Haverford College, with whom Brad and I had worked in the "ban the bomb" movement, Barbara Deming, an eloquent writer and seasoned CNVA activist, and Sherry Thurber, a young New York peace activist.

When I was chosen I began to think about staying on in Vietnam as a journalist beyond the duration of the project, and I obtained credentials as a reporter for the Catholic Worker and the National Catholic Reporter.

We arrived in Saigon on April 11, settled at the Caravelle Hotel, and began ten days of meetings and consultation with Buddhist, secular, and Catholic advocates for a peaceful, negotiated settlement of the war.

As the only Catholic I was chosen to meet with a Catholic priest and several Catholic lay people engaged in this movement. I also met with Thich Nhat Hanh, a Buddhist monk who was a key leader of young people in the Buddhist Struggle movement.

He and his students translated our literature and poster slogans into Vietnamese, prepared banners, and printed leaflets for our protest demonstration, in the Vietnamese language.

We called a press conference for April 20 to announce plans for our protest at the U.S. Embassy the following day. Vietnamese government officials prohibited our press conference, but after a dramatic day of confrontations, negotiations, and extensive interviews with reporters for worldwide media outlets, the officials sanctioned an evening press conference, giving them time to organize a raucous group of counter-protesters to disrupt the press event by shouting questions and arguments, and throwing eggs and tomatoes at us.

In this way, they tried to seize control of press coverage of our action. That day, officials also presented each of us with written notices that our visas were canceled, and we must leave Vietnam as soon as possible.

The next morning we set out to march with banners and leaflets toward the U.S. Embassy a few blocks away. We were soon arrested. loaded into vans, driven to the airport, and a few hours later loaded (with several of us being carried) onto a Pan American flight to Hong Kong.

In Saigon and Hong Kong we were surrounded by reporters and photographers who filed stories that appeared on television and in newspapers all over the United States and in many countries around the world.

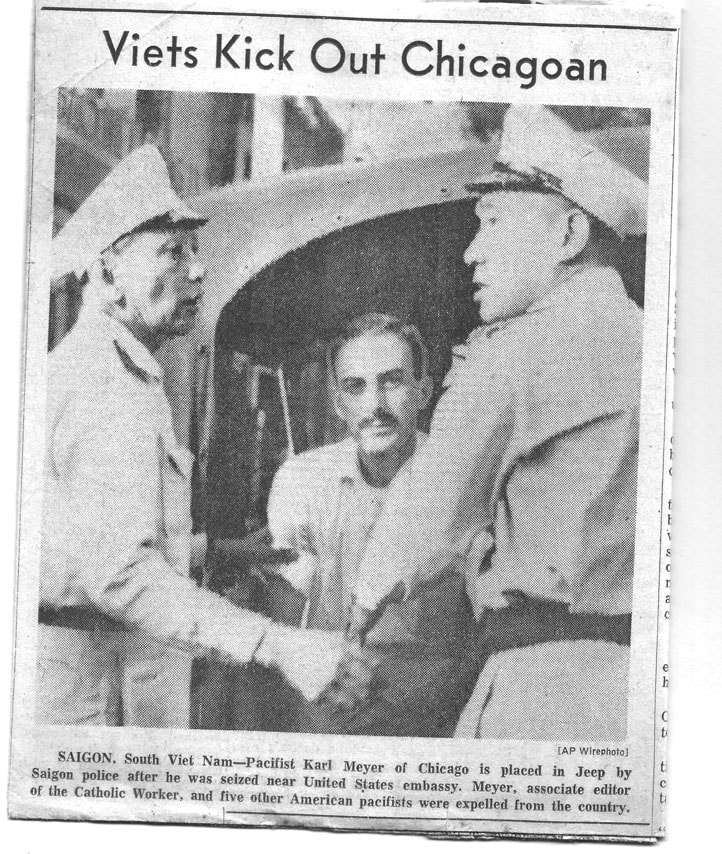

The Photograph below appeared on Page 1 of Chicago's American, on April 21

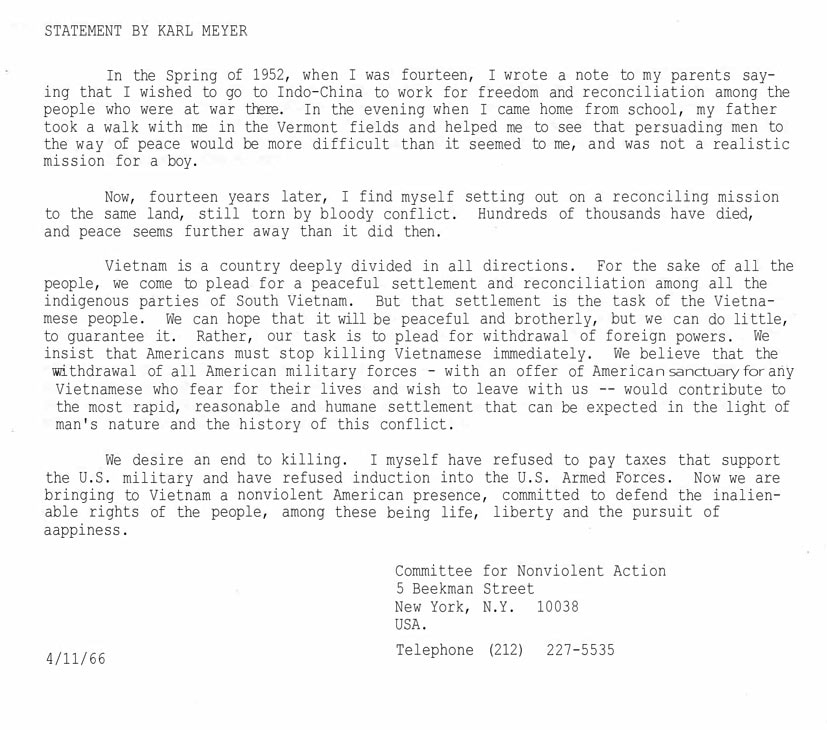

Among many documents of this project, I have selected only my individual statement of motivation, one of six statements of team members, that were distributed with leaflets and other documents to media and to the public in Saigon.

After being deported from Vietnam, I remained in Hong Kong for twenty-six days, awaiting approval of a journalist visa by Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the Cambodian Head of State. He was engaging with great political skill to save Cambodia from being dragged into military involvement in the Vietnam War.

Ultimately, he failed in this. I was running out of money in Hong Kong. And had to return to the U.S. Approval for a visa came to me on June 4, but I could not afford to return to Indochina.

Ultimately, he failed in this. I was running out of money in Hong Kong. And had to return to the U.S. Approval for a visa came to me on June 4, but I could not afford to return to Indochina.

Thich Nhat Hanh

Not long after our expulsion from Vietnam, the Fellowship of Reconciliation invited Nhat Hanh to visit the United States for a speaking tour about peace for Vietnam. He came to Chicago, and I organized public meetings for him with the peace committee of the Association of Chicago Priests, and seminarians at the diocesan Catholic Seminary.

His message inspired many of these Catholic teachers to become active in local peace movements. The American Friends Service Committee (Quakers), facilitated a meeting with Martin Luther King, who was living in Chicago that summer, leading an open housing campaign against de facto patterns of housing segregation. King later nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize. After his American tour, he was barred from returning to Vietnam, and he established a Buddhist religious community, Plum Village, in France.

In subsequent years he became one of our best-known Buddhist teachers, through several books on "mindfulness" and retreats he led on Buddhist practice during frequent visits to the United States.

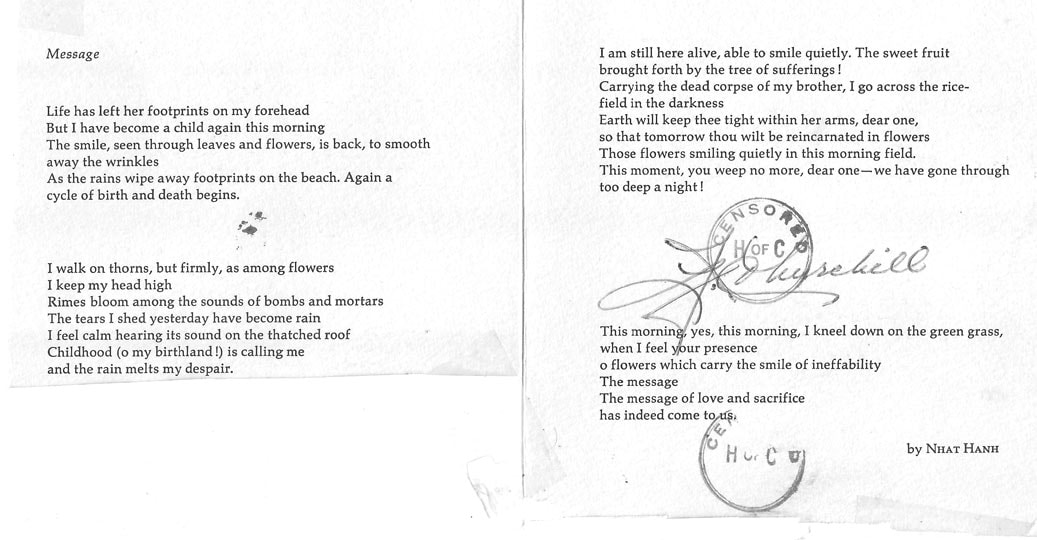

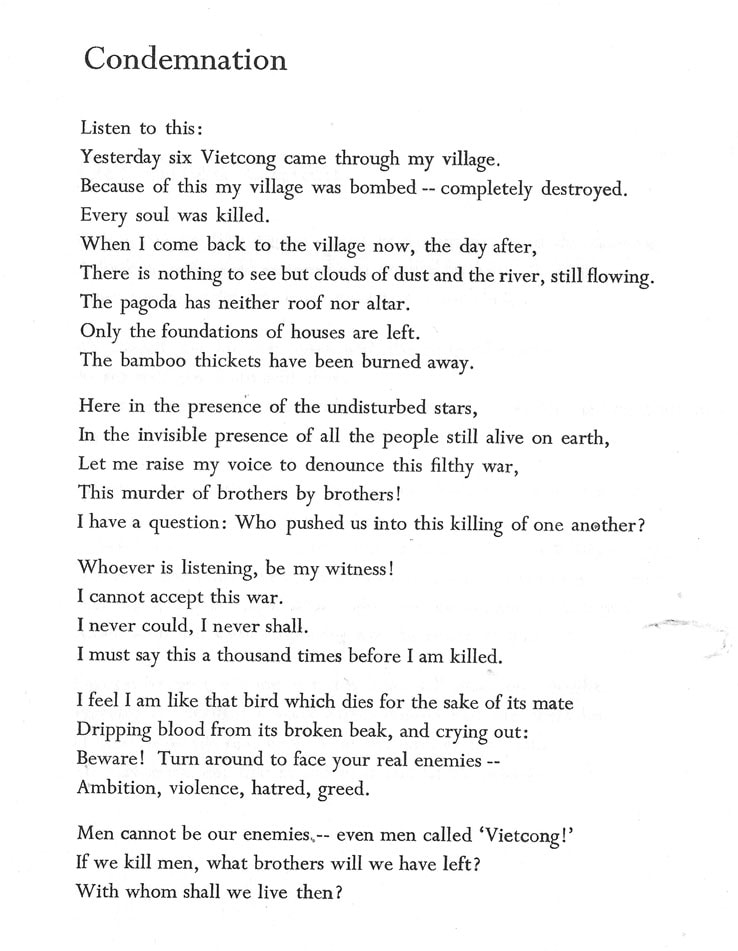

From Plum Village he sent me newsletters and a pamphlet of poems, some of which he had shown me at our Saigon meeting. I printed his poems in leaflets and read them at meetings whenever I was invited to speak about Vietnam in subsequent years. Two of the most powerful poems are reproduced here. The text of the first is copied from a greeting card sent to me by a supporter when I was in federal prison in 1971, for war tax refusal leadership. This copy bears the censorship stamp from the prison mailroom.

His message inspired many of these Catholic teachers to become active in local peace movements. The American Friends Service Committee (Quakers), facilitated a meeting with Martin Luther King, who was living in Chicago that summer, leading an open housing campaign against de facto patterns of housing segregation. King later nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize. After his American tour, he was barred from returning to Vietnam, and he established a Buddhist religious community, Plum Village, in France.

In subsequent years he became one of our best-known Buddhist teachers, through several books on "mindfulness" and retreats he led on Buddhist practice during frequent visits to the United States.

From Plum Village he sent me newsletters and a pamphlet of poems, some of which he had shown me at our Saigon meeting. I printed his poems in leaflets and read them at meetings whenever I was invited to speak about Vietnam in subsequent years. Two of the most powerful poems are reproduced here. The text of the first is copied from a greeting card sent to me by a supporter when I was in federal prison in 1971, for war tax refusal leadership. This copy bears the censorship stamp from the prison mailroom.

In the summer of 1966, I also researched and wrote a leaflet on refusal to pay the 10% telephone excise tax, which had been enacted by Congress to raise extra revenue to cover Vietnam War costs. Publication of this leaflet led to a mass movement of telephone excise tax refusal over the rest of the war years. (See War Tax Refusal sub-page.)

Chicago Peace Council - Marches and Rallies

Jack Spiegel (a regional President of the Shoe Workers Union) was the principal organizer and leader of the Chicago Peace Council, a broad coalition of secular peace groups, religious groups, labor unions, and socialist and Marxist parties of every persuasion and faction, both Communist and Trotskyist, all working together to end the Vietnam War.

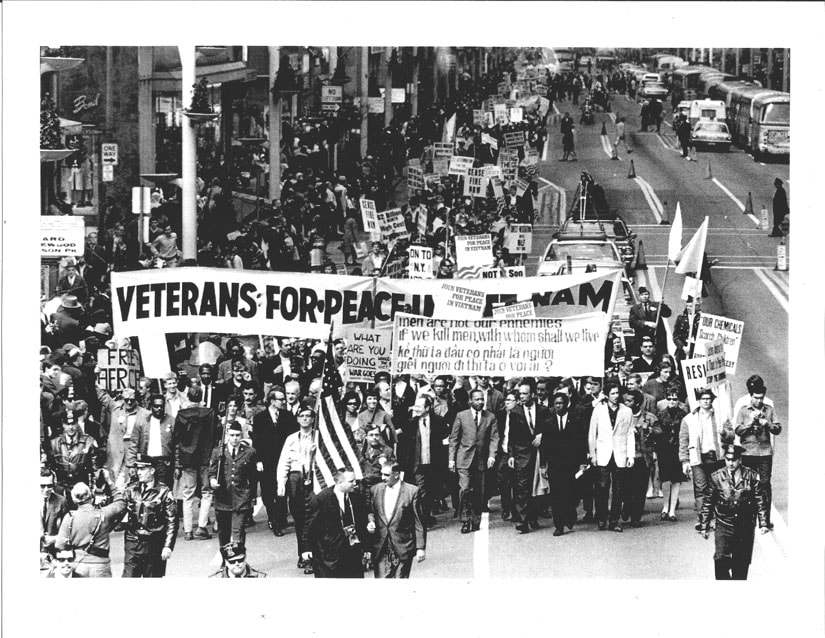

After my return from Vietnam, Jack asked me to accept nomination as Chair of the Council for the following year. In the Spring of 1967 we invited Martin Luther King to march with us in opposition to the war, and to be the keynote speaker at our mass rally after the march.

He joined us in leading a mass march on March 25. This was the first time he marched and spoke out publicly against the war, having felt restrained earlier in order not to alienate President Johnson in the campaigns for the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act.

We marched under the banner in Vietnamese and English, made by Nhat Hanh's students, which I had brought back from our action in Saigon. The photograph below is from Page 1 of the Chicago Sun-Times, March 26, 1967. Jack Spiegel is at King's right. I am in the second row, to King's left, under the ? on the banner. Sgt. O'Malley is in front -center.

After my return from Vietnam, Jack asked me to accept nomination as Chair of the Council for the following year. In the Spring of 1967 we invited Martin Luther King to march with us in opposition to the war, and to be the keynote speaker at our mass rally after the march.

He joined us in leading a mass march on March 25. This was the first time he marched and spoke out publicly against the war, having felt restrained earlier in order not to alienate President Johnson in the campaigns for the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act.

We marched under the banner in Vietnamese and English, made by Nhat Hanh's students, which I had brought back from our action in Saigon. The photograph below is from Page 1 of the Chicago Sun-Times, March 26, 1967. Jack Spiegel is at King's right. I am in the second row, to King's left, under the ? on the banner. Sgt. O'Malley is in front -center.

Vietnam Forum and Lions Convention Action - 1967

In Summer of 1967, with the support of Chicago Area Draft Resisters and Northside Women For Peace, I organized an open-air soapboxing forum for Friday and Saturday evenings, near the center of the crowded North Wells Street nightclub district. The "Vietnam Forum" launched on my birthday, June 30, and hosted speakers on Vietnam issues on multiple weekends in July, August and September.

Meanwhile, from July 5-8, the Lion's Club International held a huge convention at the Chicago Stadium. U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk, a principal defender of the Vietnam War, was scheduled as keynote speaker on July 6. I obtained a press credential as Associate Editor for the Catholic Worker, and with Renee' Schwartz and Richard Morison, took seats in the press gallery near the stage.

When Rusk rose to speak we took cloth banners from under our shirts, including the banner brought back from Vietnam and used in the Peace Council march, and unfurled them over the balcony railing, while I shouted to Rusk to hear the words of those who loved Vietnam.

The Alabama Lions delegation seated in the row behind us swarmed over a railing and ripped the banners from our hands. We were arrested, and released on bond that day, on a charge of disorderly conduct. The banners were never returned to me.

Eight days later, on Bastille Day, July 14, late in the evening, Sgt. O'Malley of the Police "Red Squad" and other officers present became tired of watching the Vietnam Forum while I was on the soapbox, and ordered the tiny crowd still present to disperse.

I refused to leave and was arrested on charges of disorderly conduct and disobeying police in the conduct of their duties.

Sgt. O'Malley, as a witness in both the Lions case and this arrest, arranged for arraignment in both cases for July 17, I pled guilty in the Lions Convention case, and not guilty in the Forum case. Representing myself pro se, I was tried and convicted by Judge Limperis, who angrily accused me of being a "professional agitator" (though I have never been paid for such agitation).

He imposed maximum fines of $200 in the Lions case and $300 in the Forum Case. When I refused to pay the fines, he remanded me to the House of Correction to work them off at a rate of $5 per day. After forty days, I was released from jail, and spoke at the Vietnam Forum the following night.

While I was serving this sentence, My friend Marshall Patner, a dedicated public interest and civil liberties lawyer, came to the jail and persuaded me to let him appeal the Forum conviction, on the "heckler's veto" issue, arising when opposition and hecklers interrupt First Amendment speech, causing the speakers to be arrested and the meeting disrupted. The Illinois Supreme Court overturned the disorderly conduct conviction, finding that my actions had been in no way disorderly, but upheld the disobeying police officers conviction. Marshall appealed to the U. S. Supreme Court, but it did not accept the case for review, though Justices Douglas, Brennan and Marshall voted to hear it.

Meanwhile, from July 5-8, the Lion's Club International held a huge convention at the Chicago Stadium. U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk, a principal defender of the Vietnam War, was scheduled as keynote speaker on July 6. I obtained a press credential as Associate Editor for the Catholic Worker, and with Renee' Schwartz and Richard Morison, took seats in the press gallery near the stage.

When Rusk rose to speak we took cloth banners from under our shirts, including the banner brought back from Vietnam and used in the Peace Council march, and unfurled them over the balcony railing, while I shouted to Rusk to hear the words of those who loved Vietnam.

The Alabama Lions delegation seated in the row behind us swarmed over a railing and ripped the banners from our hands. We were arrested, and released on bond that day, on a charge of disorderly conduct. The banners were never returned to me.

Eight days later, on Bastille Day, July 14, late in the evening, Sgt. O'Malley of the Police "Red Squad" and other officers present became tired of watching the Vietnam Forum while I was on the soapbox, and ordered the tiny crowd still present to disperse.

I refused to leave and was arrested on charges of disorderly conduct and disobeying police in the conduct of their duties.

Sgt. O'Malley, as a witness in both the Lions case and this arrest, arranged for arraignment in both cases for July 17, I pled guilty in the Lions Convention case, and not guilty in the Forum case. Representing myself pro se, I was tried and convicted by Judge Limperis, who angrily accused me of being a "professional agitator" (though I have never been paid for such agitation).

He imposed maximum fines of $200 in the Lions case and $300 in the Forum Case. When I refused to pay the fines, he remanded me to the House of Correction to work them off at a rate of $5 per day. After forty days, I was released from jail, and spoke at the Vietnam Forum the following night.

While I was serving this sentence, My friend Marshall Patner, a dedicated public interest and civil liberties lawyer, came to the jail and persuaded me to let him appeal the Forum conviction, on the "heckler's veto" issue, arising when opposition and hecklers interrupt First Amendment speech, causing the speakers to be arrested and the meeting disrupted. The Illinois Supreme Court overturned the disorderly conduct conviction, finding that my actions had been in no way disorderly, but upheld the disobeying police officers conviction. Marshall appealed to the U. S. Supreme Court, but it did not accept the case for review, though Justices Douglas, Brennan and Marshall voted to hear it.

1968-72 More Actions & The "Battle of Chicago"

In late1967, IRS collection agents came to my place of employment and served notice to garnishee my wages to collect claims for income taxes I had not paid. I resigned to prevent collection, and went to work as an unpaid volunteer at the American Friends Service Committee with the purpose of organizing opposition to the war among local Catholic communities.

Working with the peace committee of the Association of Chicago Priests, I organized educational meetings with Thich Nhat Hanh, and with Fr. Daniel Berrigan S.J., my long-time friend and religious adviser, who was becoming one of the best-known and most influential Catholic peace activists in the United States.

With Joe Mulligan, S.J., and Phil Dahl-Bredine I also organized a series of peace meetings with small groups of Catholics in parishes served by members of the ACP peace committee. We called this project "The Samaritan Church" to highlight the idea of attending to the suffering of people in a foreign land.

1968 was a year of dramatic events. Martin Luther King was murdered on April 4, and the impoverished African-American neighborhood where my family's home and Catholic Worker shelter for homeless guests was located, exploded in riots, flames and gunfire, with National Guard troops and vehicles up and down our street. Our house was not threatened, but I was assaulted and robbed three times that year coming and going from the house.

The National Convention of the Democratic Party was scheduled to meet in Chicago in August, and national and local peace organizations were preoccupied for months with preparations for protests against the Vietnam War. Working full-time to support my family and guests in our shelter, and organizing educational work with Catholic communities, I did not get much involved with Peace Council preparations for the Democratic Convention.

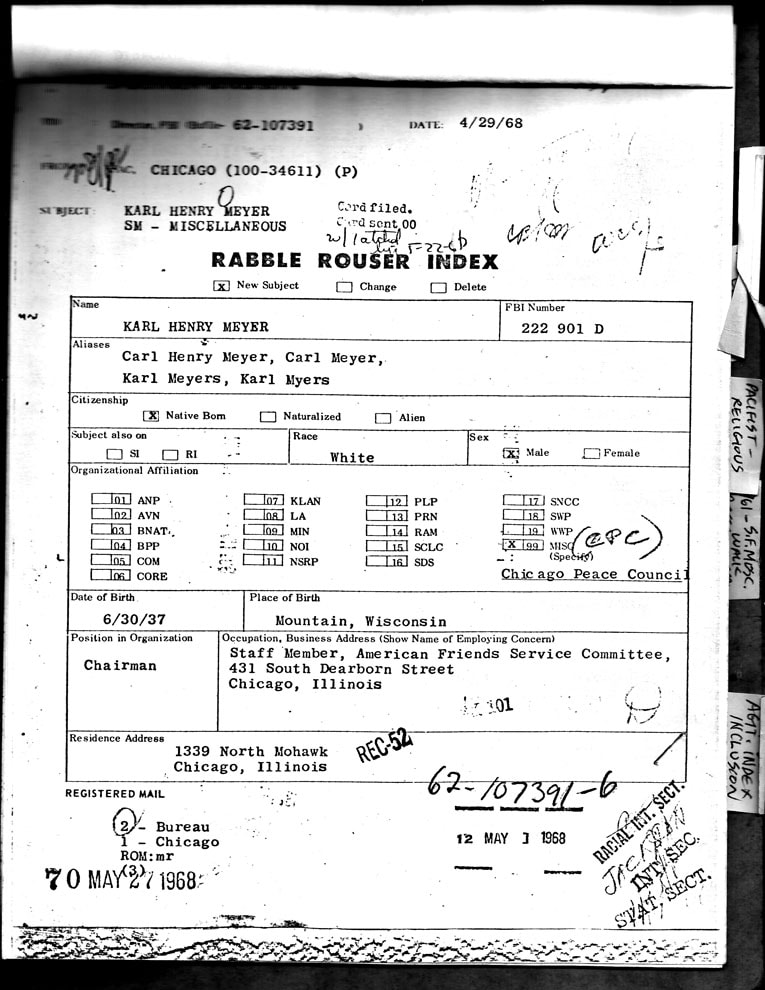

The FBI took note of this. (Using the new Freedom of Information Act in the late 70s and early 80s, I was able to obtain, CIA, Air Force and Chicago Police "Red Squad" files about me, and extensive FBI Washington Office files reporting on my peace activities from 1957 through 1978, usually accurately, but sometimes in error.) In April 1968, in a Memorandum to the Director, they added me to their "Rabble Rouser Index":

I never used any of the "aliases" listed. They are presumably mis-spellings of my name by informants who heard my name spoken at meetings.

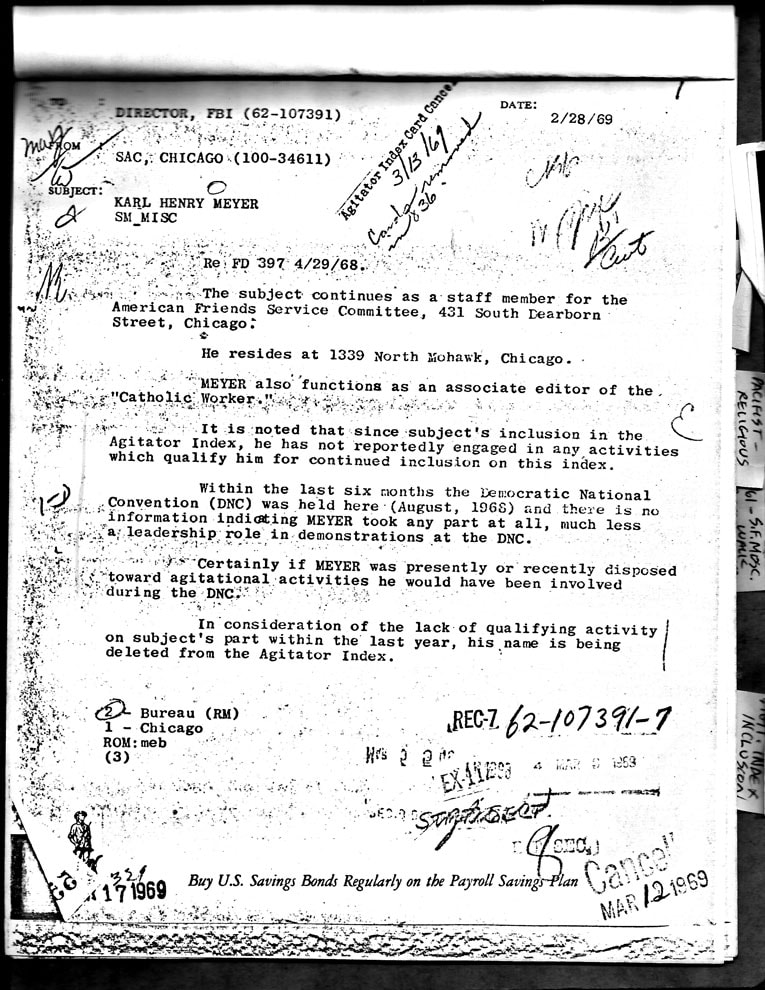

In February 1969 they dumped me from the index, as explained in the memorandum below:

In February 1969 they dumped me from the index, as explained in the memorandum below:

I was offended when I read this, as it is quite inaccurate. I was tear-gassed with Dick Gregory and hundreds of others at Michigan Ave. and Roosevelt Rd. one evening as we tried to march south to the Amphitheater where the Convention was meeting.

On the night of the "Battle of Chicago" , I was near the front of a huge crowd in Grant Park, across the street from the Conrad Hilton Hotel, and I waved across the police line to Morton Franklin, a policeman who had infiltrated the Chicago Peace Council under the alias Marty Frankel and sought credibility with me by speaking against the war, as a veteran, at my Vietnam Forum the previous summer. He blew his cover when he testified as a prosecution witness at the famous Chicago Seven conspiracy trial in 1969-70.

In fact, 1968-'72 were my most effective years of rousing the rabble against the war, as my writings on telephone tax refusal and use of the W-4 Form to prevent withholding of federal income tax from wages were widely reprinted and circulated sparking and informing mass movements of war tax refusal.

In 1970, after I spread a poster of My Lai massacre victims on the desk of the IRS District Director during an April demonstration at the Chicago office, he initiated a criminal investigation of my tax refusal. I was indicted on April 15, 1971 on five counts of W-4 Form fraud, was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison. After serving nine months at Cook County Jail and Sandstone, M.N., Federal Correctional Institution, I was paroled for another fifteen months, in February 1972.

Soon after the signing of the Paris Accords to end the war in Vietnam, in January 1973, the U.S. combat role in Vietnam ended, and our protest organizations wound down their work, though committed draft refusers and military tax refusers continued our resistance. (See more detail on these movements on the Draft Refusal, War Tax Refusal, and Prison pages of this website.)

On the night of the "Battle of Chicago" , I was near the front of a huge crowd in Grant Park, across the street from the Conrad Hilton Hotel, and I waved across the police line to Morton Franklin, a policeman who had infiltrated the Chicago Peace Council under the alias Marty Frankel and sought credibility with me by speaking against the war, as a veteran, at my Vietnam Forum the previous summer. He blew his cover when he testified as a prosecution witness at the famous Chicago Seven conspiracy trial in 1969-70.

In fact, 1968-'72 were my most effective years of rousing the rabble against the war, as my writings on telephone tax refusal and use of the W-4 Form to prevent withholding of federal income tax from wages were widely reprinted and circulated sparking and informing mass movements of war tax refusal.

In 1970, after I spread a poster of My Lai massacre victims on the desk of the IRS District Director during an April demonstration at the Chicago office, he initiated a criminal investigation of my tax refusal. I was indicted on April 15, 1971 on five counts of W-4 Form fraud, was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison. After serving nine months at Cook County Jail and Sandstone, M.N., Federal Correctional Institution, I was paroled for another fifteen months, in February 1972.

Soon after the signing of the Paris Accords to end the war in Vietnam, in January 1973, the U.S. combat role in Vietnam ended, and our protest organizations wound down their work, though committed draft refusers and military tax refusers continued our resistance. (See more detail on these movements on the Draft Refusal, War Tax Refusal, and Prison pages of this website.)