Military Draft Actions

As a teenager in Vermont in the 1950s I had formed pacifist convictions in opposition to all wars, and as a conscientious objector to personal participation in any war or any military service. In early 1955, facing the legal obligation upon all young men in the United States at that time to register at age eighteen for the military draft, I decided to register and to seek the 1-O classification as a religious conscientious objector, which would allow for two years of civilian public service, if called up, as an alternative to military service.

After an interview to determine my sincerity, and an FBI investigation, a local Draft Board in New York City, granted me the 1-O classification.

Influenced by my Catholic Worker mentor, Ammon Hennacy, I moved in the direction of total non-cooperation with the Selective Service System [military conscription process]. In January 1959 I acted by tearing my draft cards in half and returning them to the Draft Board with a cover letter declaring my intent to refuse any future compliance.

The Board reacted by revoking the 1-O classification, reclassifying me as 1-A (available for military service), and ordering me to report for a physical exam and induction on May 19. I returned the notice, and did not appear. This refusal was a federal felony, carrying a possible penalty of five years in prison.

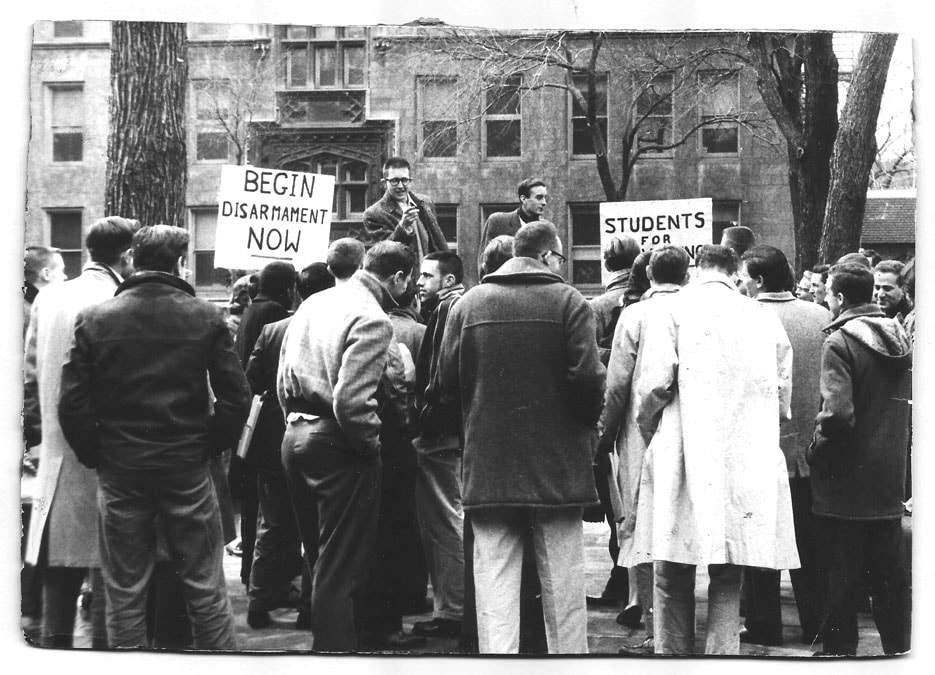

In early 1959 I also joined with Ken Calkins and several other students at the University of Chicago in forming the first chapter of a Student Peace Union, which under Ken's leadership soon developed into a national organization with chapters on many college campuses around the United States.

Ken Calkins and Karl soapboxing at the University of Chicago campus - May 1959, shortly after formation of the Student Peace Union

In 1959 and 1960 issues of the Student Peace Union Bulletin I wrote frequent articles advocating radical resistance to military conscription, military taxes, and weapons programs.

When I was sent to federal prison for six months in 1959, for trespassing at a ballistic missile site, the Local Board reclassified me again, as 4-F (unsuitable for military service), and sent me new cards at the prison camp. I tore these cards in half and mailed them back to the Board, and did not hear from them again.

In 1964, as U.S. involvement in the Vietnamese civil war began to escalate, Gene Keyes, Russ Goddard and Barry Bassin published a pact declaring their non-cooperation with military conscription, and resolving to regard an arrest of one as an arrest of all; they cited my 1960 jail solidarity with tax refuser Eroseanna Robinson as a model for their action.

By 1965, all three were in prison for draft resistance. Gene Keyes wrote to me, "For whatever reason, you keep bobbing up as a prototype for things I get into." In 1963 he had burned his draft cards publicly in front of his local draft board in Champaign, Illinois.

By 1965, public burning of draft cards by individuals and small groups emerged as a dramatic symbol of resistance to conscription for the expanding Vietnam War. Congress reacted by enacting a law, making destruction of draft cards a felony punishable by up to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

President Johnson signed the bill on August 31. As soon as this law passed, I saw the political importance of openly defying it. On September 4, I wrote to my draft board in New York, asking them to issue new draft cards to me, which they did. I then tore them in half, and mailed the evidence to the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois with a cover letter explaining my reasons:

"…I agree with the young men who have destroyed their draft cards, and I want to give them concrete support and encouragement…The mutilation of human beings in Vietnam has become a civic virtue; now the mutilation of a scrap of paper becomes a grave crime against the state. But the cry of conscience cannot be so easily suppressed…A vast military machine rolls past me into Vietnam, over a highway of broken human lives, lives of Americans as well as Vietnamese. I feel anguish for the suffering of the victims and for the blindness of the executioners. I know that I cannot stop this crime, but as long as my voice is free, I will still cry out against it."

I sent copies of this letter to the Catholic Worker, the Peacemaker, and News Notes of the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors. Excerpts were published in these papers. My FBI files, which I obtained in 1977 under the Freedom of Information Act, show a conclusion by the U.S. Attorney's office that it would not be in the interests of the U.S. Government to prosecute me for this crime because of the publicity that would result.

On October 15, 1965, David Miller of the New York Catholic Worker community became the first person to burn his draft card in a public ceremony, defying the new law. He was prosecuted and sent to prison for thirty months. On November 6, another Catholic Worker, Tom Cornell joined four other activists in a public draft card burning, with A.J. Muste and Dorothy Day on the platform to support them. Tom credited me with influencing him toward this action. He got six months in prison.

When I was sent to federal prison for six months in 1959, for trespassing at a ballistic missile site, the Local Board reclassified me again, as 4-F (unsuitable for military service), and sent me new cards at the prison camp. I tore these cards in half and mailed them back to the Board, and did not hear from them again.

In 1964, as U.S. involvement in the Vietnamese civil war began to escalate, Gene Keyes, Russ Goddard and Barry Bassin published a pact declaring their non-cooperation with military conscription, and resolving to regard an arrest of one as an arrest of all; they cited my 1960 jail solidarity with tax refuser Eroseanna Robinson as a model for their action.

By 1965, all three were in prison for draft resistance. Gene Keyes wrote to me, "For whatever reason, you keep bobbing up as a prototype for things I get into." In 1963 he had burned his draft cards publicly in front of his local draft board in Champaign, Illinois.

By 1965, public burning of draft cards by individuals and small groups emerged as a dramatic symbol of resistance to conscription for the expanding Vietnam War. Congress reacted by enacting a law, making destruction of draft cards a felony punishable by up to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

President Johnson signed the bill on August 31. As soon as this law passed, I saw the political importance of openly defying it. On September 4, I wrote to my draft board in New York, asking them to issue new draft cards to me, which they did. I then tore them in half, and mailed the evidence to the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois with a cover letter explaining my reasons:

"…I agree with the young men who have destroyed their draft cards, and I want to give them concrete support and encouragement…The mutilation of human beings in Vietnam has become a civic virtue; now the mutilation of a scrap of paper becomes a grave crime against the state. But the cry of conscience cannot be so easily suppressed…A vast military machine rolls past me into Vietnam, over a highway of broken human lives, lives of Americans as well as Vietnamese. I feel anguish for the suffering of the victims and for the blindness of the executioners. I know that I cannot stop this crime, but as long as my voice is free, I will still cry out against it."

I sent copies of this letter to the Catholic Worker, the Peacemaker, and News Notes of the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors. Excerpts were published in these papers. My FBI files, which I obtained in 1977 under the Freedom of Information Act, show a conclusion by the U.S. Attorney's office that it would not be in the interests of the U.S. Government to prosecute me for this crime because of the publicity that would result.

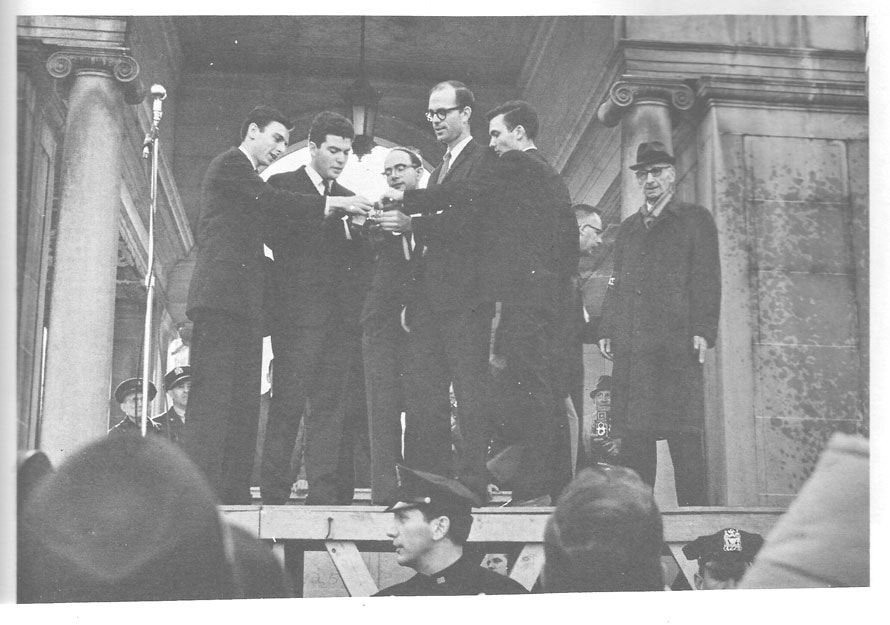

On October 15, 1965, David Miller of the New York Catholic Worker community became the first person to burn his draft card in a public ceremony, defying the new law. He was prosecuted and sent to prison for thirty months. On November 6, another Catholic Worker, Tom Cornell joined four other activists in a public draft card burning, with A.J. Muste and Dorothy Day on the platform to support them. Tom credited me with influencing him toward this action. He got six months in prison.

Tom Cornell, Marc Paul Edelman, Roy Lisker, Dave McReynolds, Jim Wilson, A.J. Muste Burning draft cards, November 6, 1965 [Photo: Neil Haworth]

In the next few years group draft card burnings became common. On April 15, 1967, one-hundred, seventy-five men burned cards at a mass peace rally in New York's Central Park. In October, fifteen-hundred non-cooperators returned draft cards to Selective Service in a coordinated action. In their book on resistance to conscription during the Vietnam War, Michael Ferber and Staughton Lynd credit me with substantial influence in the early development of radical draft refusal during the war. (The Resistance, Beacon Press, 1971, pages 10, 11, 16)

I continued to advocate all forms of draft refusal and war tax refusal, at Chicago Peace Council meetings and events, and in the Catholic Worker and other peace movement periodicals throughout the Vietnam War.

I continued to advocate all forms of draft refusal and war tax refusal, at Chicago Peace Council meetings and events, and in the Catholic Worker and other peace movement periodicals throughout the Vietnam War.

1980-81 Actions

In early 1980, the Soviet Union was engaged in a neo-colonial intervention in Afghanistan to suppress armed revolt against a Soviet client government. U.S. President Jimmy Carter announced several policy initiatives allegedly aimed at pressuring the Soviet Union to withdraw from the Afghan War. One initiative in July was to return to registering young men for possible military conscription.

Congress had ended the military draft in 1973, after the Vietnam War, and provided for an all-volunteer Army, and President Ford had suspended draft registration in 1975.

Restoring registration probably had little to do with the Afghan War, but was a policy experiment to see if actual military conscription might be introduced later. Men born in 1960, 1961, or 1962, were to register during designated periods in July and August 1980, and in January 1981. After that all men turning eighteen were to register within thirty days of their birthdays. U.S. Post Offices were designated as registration sites. The maximum criminal penalty for failing to register was set at five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

In Chicago and around the country some of us recognized the importance of organizing prompt mass resistance to the registration mandate to prevent restoration of conscription. I cooperated with Johnny Rossen, an aging radical of my parent's generation, and with Matt Nicodemus and Ed Hasbrouck, two young men nearing age eighteen who publicly declared their refusal to register, in organizing resistance protests and actions in Chicago. I took time off from work to organize nonviolent actions, gathering lots of support from the Catholic Worker community and friends in other Chicago movements.

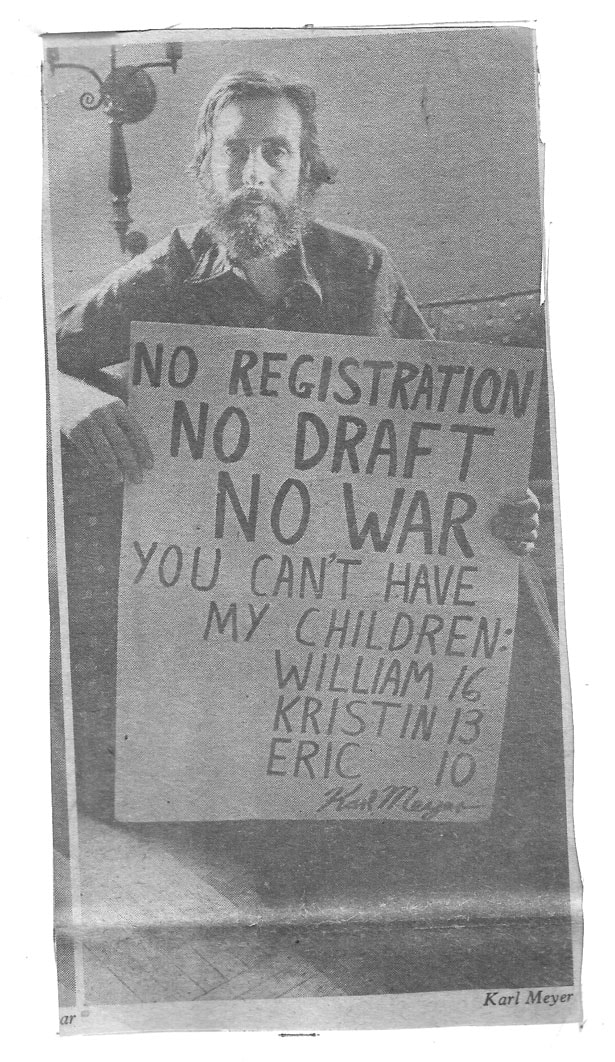

I made a sign reading, "No Registration, No Draft, No War - You can't have my children: William 16, Kristin 13, Eric 10". I was arrested, with others, seven times during the July and August registration windows for handing out leaflets and singing anti-war songs at the registration table inside the main Post Office at the downtown Federal Buildings Plaza. Kathy Kelly was arrested with us five times.

My son William was with us on January 5, 1981. We had several interesting trial appearances in Federal courts, some resulting in dismissal of charges, and others in nominal fines that we never paid. These actions brought lots of media and public attention to our anti-draft movements.

Congress had ended the military draft in 1973, after the Vietnam War, and provided for an all-volunteer Army, and President Ford had suspended draft registration in 1975.

Restoring registration probably had little to do with the Afghan War, but was a policy experiment to see if actual military conscription might be introduced later. Men born in 1960, 1961, or 1962, were to register during designated periods in July and August 1980, and in January 1981. After that all men turning eighteen were to register within thirty days of their birthdays. U.S. Post Offices were designated as registration sites. The maximum criminal penalty for failing to register was set at five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

In Chicago and around the country some of us recognized the importance of organizing prompt mass resistance to the registration mandate to prevent restoration of conscription. I cooperated with Johnny Rossen, an aging radical of my parent's generation, and with Matt Nicodemus and Ed Hasbrouck, two young men nearing age eighteen who publicly declared their refusal to register, in organizing resistance protests and actions in Chicago. I took time off from work to organize nonviolent actions, gathering lots of support from the Catholic Worker community and friends in other Chicago movements.

I made a sign reading, "No Registration, No Draft, No War - You can't have my children: William 16, Kristin 13, Eric 10". I was arrested, with others, seven times during the July and August registration windows for handing out leaflets and singing anti-war songs at the registration table inside the main Post Office at the downtown Federal Buildings Plaza. Kathy Kelly was arrested with us five times.

My son William was with us on January 5, 1981. We had several interesting trial appearances in Federal courts, some resulting in dismissal of charges, and others in nominal fines that we never paid. These actions brought lots of media and public attention to our anti-draft movements.

Chicago Reader, page 1, September 5, 1980 - Photo: Diane Schmidt

The October 19, 1981, the Chicago Sun Times reported that the FBI had referred to the U.S. Attorney's office the names of seventy-five Chicago area men who had failed to register, and an Assistant U.S. Attorney was quoted as saying, "Congress set the law and we're going to do our duty." I conceived a plan to discourage prosecutions in the Northern District of Illinois. I contacted leaders of all major peace organizations and asked them to go on a delegation to the United States Attorney.

Seventeen organizations offered support. I arranged a meeting with U.S. Attorney Dan Webb for December 16. The final delegation included leaders from twelve organizations, plus Bernard Harkin, a public resister, Matt Nicodemus' mother Virginia, and Harvey Grossman for the American Civil Liberties Union. Dan Webb had with him one of his top Assistants and the Agent-in-Charge for the Chicago FBI office. One after the other we all made clear to them that we would give vigorous organizational support to any young men prosecuted in the Northern District.

In my remarks in behalf of the whole delegation, I emphasized that most of us were veteran activists, with well-organized constituencies, and long political memories. U.S. Attorneys are political appointees of a sitting President, ambitious people who often go on to run for mayor, governor, or U.S. Senator.

It is unwise for them to alienate organized groups of politically active citizens. Dan Webb did not speak long in response, mainly indicating that he had heard clearly what we had to say. Subsequently, no registration refusers were prosecuted in the Northern District of Illinois. Following our meeting, similar delegations were organized to meet with U.S. Attorneys in other jurisdictions. Prosecutions for non-registration have been few, but Congress enacted legislation denying federal aid or federal jobs to young men who fail to register.

Seventeen organizations offered support. I arranged a meeting with U.S. Attorney Dan Webb for December 16. The final delegation included leaders from twelve organizations, plus Bernard Harkin, a public resister, Matt Nicodemus' mother Virginia, and Harvey Grossman for the American Civil Liberties Union. Dan Webb had with him one of his top Assistants and the Agent-in-Charge for the Chicago FBI office. One after the other we all made clear to them that we would give vigorous organizational support to any young men prosecuted in the Northern District.

In my remarks in behalf of the whole delegation, I emphasized that most of us were veteran activists, with well-organized constituencies, and long political memories. U.S. Attorneys are political appointees of a sitting President, ambitious people who often go on to run for mayor, governor, or U.S. Senator.

It is unwise for them to alienate organized groups of politically active citizens. Dan Webb did not speak long in response, mainly indicating that he had heard clearly what we had to say. Subsequently, no registration refusers were prosecuted in the Northern District of Illinois. Following our meeting, similar delegations were organized to meet with U.S. Attorneys in other jurisdictions. Prosecutions for non-registration have been few, but Congress enacted legislation denying federal aid or federal jobs to young men who fail to register.

The Future of Draft Registration and Conscription

As of this writing in 2020, a U.S. District Court judge has ruled that because women are presently permitted in combat roles and many other positions in the U.S. military, the registration requirement for men alone violates the equal protection requirements of the U.S. Constitution by discriminating against men on the basis of sex.

This legal issue is currently pending resolution in the appeals process. Meanwhile, Congress punted on the draft registration question by creating a National Commission on Military, National and Public Service. This Commission has recently recommended that Congress resolve the Constitutional issue by extending the registration requirement to young women as well as men.

It has also suggested consideration of a universal requirement that all young people in the United States be subject to conscription for a period of public service, either in the military or in needed civilian service occupations. While a voluntary program of offering paid employment to young people in valuable public services, such as needed healthcare workers and teaching assistants in understaffed public schools, could be socially valuable, compulsory conscription would violate the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, providing that, "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

For forty years, registration without conscription powers has been a total and irrational waste of resources. If Congress might at some point decide that restoration of conscription was necessary, the government could quickly compile a list of eligible persons from other, more up-to-date data sources.

All draft registration should be ended. If the requirement is extended to women, I expect to be in the forefront of efforts to encourage all young people to refuse to comply.

This legal issue is currently pending resolution in the appeals process. Meanwhile, Congress punted on the draft registration question by creating a National Commission on Military, National and Public Service. This Commission has recently recommended that Congress resolve the Constitutional issue by extending the registration requirement to young women as well as men.

It has also suggested consideration of a universal requirement that all young people in the United States be subject to conscription for a period of public service, either in the military or in needed civilian service occupations. While a voluntary program of offering paid employment to young people in valuable public services, such as needed healthcare workers and teaching assistants in understaffed public schools, could be socially valuable, compulsory conscription would violate the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, providing that, "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

For forty years, registration without conscription powers has been a total and irrational waste of resources. If Congress might at some point decide that restoration of conscription was necessary, the government could quickly compile a list of eligible persons from other, more up-to-date data sources.

All draft registration should be ended. If the requirement is extended to women, I expect to be in the forefront of efforts to encourage all young people to refuse to comply.