Central America Solidarity Actions -

1980s

Struggles for liberation from economic and political oligarchies emerged in Central America in the late 70s and early 80s. A similar wave of rebellions had been suppressed in the 1930s. U.S. policy and military aid supported status quo oligarchies, and the CIA and U.S. Army for decades had intervened frequently to foster and support military coups d'etat to overthrow popular elected governments.

El Salvador

In El Salvador, a coalition of young military officers, organized workers, educators and progressive politicians won some progress toward reform in 1979 and 1980. In the face of savage repression from military and paramilitary "death squads" that murdered thousands of dissenters and anyone suspected of supporting them, parties of rebels retreated into the mountains and rural villages to undertake armed guerilla insurrection.

The progressive Catholic Archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Romero, became a charismatic leader of popular struggle for liberation and human rights. On March 24, 1980, he was gunned down at the altar while saying Mass in a chapel of the community where he lived. On December 2, three nuns and a laywoman from the United States, who worked with poor villagers in rural El Salvador, were kidnapped, raped, murdered and buried by the roadside.

News of these killings brought our attention to the much wider pattern of death squad killings and military repression. The U.S. Government was providing millions of dollars in weapons, training and other aid to the Salvadoran Armed Forces and Government.

In 1981, I began attending meetings of solidarity organizations in Chicago. I conceived a plan for a portable kiosk with five walls, for displaying educational photographs and information on the human rights crisis in El Salvador. I transported it in my station wagon. With legal help from the American Civil Liberties Union, I was able to get a permit to set it up regularly in the Federal Building Plaza in downtown Chicago. I also took it around to college campuses and other venues over several months in 1982.

That spring, cooperating with the Chicago Religious Task Force on Central America (CRTF), I also organized a blood drive with the goal of donating blood in memory of many named victims of death squads. Local blood banks brought mobile collection vehicles to the Federal Plaza for this project.

The progressive Catholic Archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Romero, became a charismatic leader of popular struggle for liberation and human rights. On March 24, 1980, he was gunned down at the altar while saying Mass in a chapel of the community where he lived. On December 2, three nuns and a laywoman from the United States, who worked with poor villagers in rural El Salvador, were kidnapped, raped, murdered and buried by the roadside.

News of these killings brought our attention to the much wider pattern of death squad killings and military repression. The U.S. Government was providing millions of dollars in weapons, training and other aid to the Salvadoran Armed Forces and Government.

In 1981, I began attending meetings of solidarity organizations in Chicago. I conceived a plan for a portable kiosk with five walls, for displaying educational photographs and information on the human rights crisis in El Salvador. I transported it in my station wagon. With legal help from the American Civil Liberties Union, I was able to get a permit to set it up regularly in the Federal Building Plaza in downtown Chicago. I also took it around to college campuses and other venues over several months in 1982.

That spring, cooperating with the Chicago Religious Task Force on Central America (CRTF), I also organized a blood drive with the goal of donating blood in memory of many named victims of death squads. Local blood banks brought mobile collection vehicles to the Federal Plaza for this project.

El Salvador Human Rights Center 5-7-82 Memorial Blood Drive 6-5-82

Nicaragua and Guatemala

In 1979, the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua succeeded in overthrowing the Somoza family dictatorship, which had come to power in the 1930s with U.S. support. A coalition of Marxists, progressive Christians, and other reformers established a democratic socialist government.

Counter-revolutionary Somoza supporters (Contras) took refuge in neighboring Honduras and began cross-border guerilla raids, with financial support and training from the new U.S Administration of President Ronald Reagan, trying to overthrow the Sandinista government.

Meanwhile, in Guatemala, military dictators were engaged in genocidal warfare against urban dissenters and rebellious indigenous communities in mountainous rural regions.

Over the seven years from 1982-1988, my second wife Kathy Kelly and I, working as a team, with Catholic Workers, CRTF, Synapses and Pledge of Resistance, organized numerous creative nonviolent actions to educate the public in Chicago, support popular movements and governments in Central America, and oppose the reactionary imperialist policies of the Reagan/Bush Administration. These actions included the following:

Kathy and I provided long term housing and sanctuary in our apartment during these years for several political refugees from Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador.

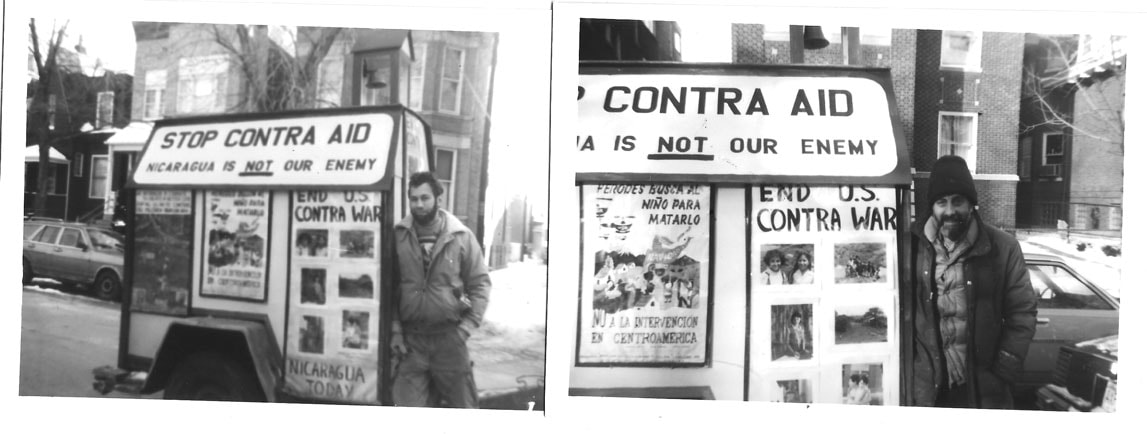

1983-'84 - The Reagan Administration sought to increase military pressure on Nicaragua from the Contras based in Honduras by introducing U.S. Armed Forces into Honduras, in exercises named "Operation Big Pines". I responded by buying a stake trailer and mounting on my station wagon and the sides of the trailer displays with simple summaries of the issues in El Salvador and Nicaragua. These educational messages were on the street 24/7 wherever I traveled or parked.

Counter-revolutionary Somoza supporters (Contras) took refuge in neighboring Honduras and began cross-border guerilla raids, with financial support and training from the new U.S Administration of President Ronald Reagan, trying to overthrow the Sandinista government.

Meanwhile, in Guatemala, military dictators were engaged in genocidal warfare against urban dissenters and rebellious indigenous communities in mountainous rural regions.

Over the seven years from 1982-1988, my second wife Kathy Kelly and I, working as a team, with Catholic Workers, CRTF, Synapses and Pledge of Resistance, organized numerous creative nonviolent actions to educate the public in Chicago, support popular movements and governments in Central America, and oppose the reactionary imperialist policies of the Reagan/Bush Administration. These actions included the following:

Kathy and I provided long term housing and sanctuary in our apartment during these years for several political refugees from Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador.

1983-'84 - The Reagan Administration sought to increase military pressure on Nicaragua from the Contras based in Honduras by introducing U.S. Armed Forces into Honduras, in exercises named "Operation Big Pines". I responded by buying a stake trailer and mounting on my station wagon and the sides of the trailer displays with simple summaries of the issues in El Salvador and Nicaragua. These educational messages were on the street 24/7 wherever I traveled or parked.

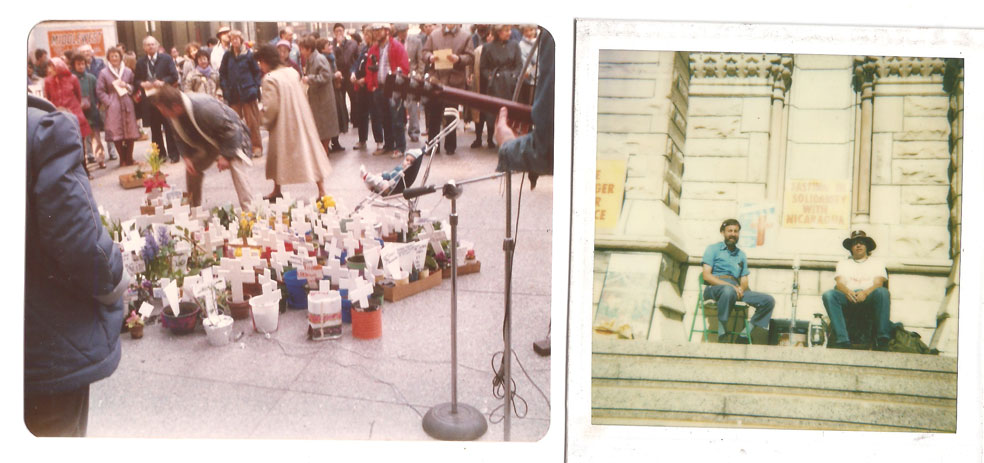

1985 - We organized a continuous vigil in the Federal Plaza from March 26-April 24 which we called the "Flowerpot Vigil."

The main visual prop was dozens of flowerpots donated by supporters, with crosses commemorating named victims of savage repression in El Salvador and Guatemala, and Contra atrocities in Nicaragua. That summer Kathy spent six weeks in Nicaragua, and joined actively in a "Nonviolent Insurrection" fast and protest against the U.S. supported Contra raids, led by the Maryknoll priest, Fr. Miguel D'Escoto, who was Nicaragua's Foreign Minister.

To call attention to D'Escoto's fast, I undertook a ten-day, fluids only fast and vigil on the steps of Chicago's Holy Name Cathedral, joined by Ron Schupp.

The main visual prop was dozens of flowerpots donated by supporters, with crosses commemorating named victims of savage repression in El Salvador and Guatemala, and Contra atrocities in Nicaragua. That summer Kathy spent six weeks in Nicaragua, and joined actively in a "Nonviolent Insurrection" fast and protest against the U.S. supported Contra raids, led by the Maryknoll priest, Fr. Miguel D'Escoto, who was Nicaragua's Foreign Minister.

To call attention to D'Escoto's fast, I undertook a ten-day, fluids only fast and vigil on the steps of Chicago's Holy Name Cathedral, joined by Ron Schupp.

Flowerpot Vigil - Federal Plaza - March '85 KM & Ron Schupp- Cathedral Vigil- July'85

1986 - Witness for Peace had published an illustrated pamphlet, "What We Have Seen and Heard", and a folio of photographs of victims of Contra raids into northern Nicaragua. I enlarged some of these photos at a copy shop and printed multiple copies on11"X17" adhesive backed paper.

On three early mornings in March, with a small group of Catholic Workers and allies from Synapses, a Mennonite social justice group, we posted many photos on the plate glass windows of the Federal Court Building. We were arrested quickly, and released within a few hours with citations for defacing Federal property. Janitors stripped the images from the glass.

When Pledge of Resistance leaders realized enforcement would be mild, they copied four hundred "Strip-Tac" posters for our scheduled spring demonstration, and a huge crowd of Pledge supporters circled the Federal Building and posted images on all the first-floor lobby windows. The police did not interfere and no one was arrested. At trial two months later, those of us originally arrested were prepared to argue that we were not defacing the windows, but instead trying to put faces on them, but all of these cases were dropped by the U.S. Attorney.

We then considered putting images on the walls of judges' courtrooms or the fronts of their high benches, but decided on a different tactic. There were twenty-three Federal Judges sitting in Chicago for the Northern District of Illinois.

We wrote a letter and petition to all of them explaining our belief that the Contra attacks against Nicaragua and the U.S. embargo against any trade with Nicaragua were illegal, and we asked them to enjoin the Reagan Administration from continuing them.

We said we would visit their courtrooms to pursue our petition. We delivered copies to all of their offices on March 27, with 166 co-signers listed. Over a three week period we visited the courtrooms of eleven judges, with a number of supporters, at motion call and challenged them to hear our case, starting with Chief Judge Frank McGarr.

He invited me and Kathy to his chambers, where he warned us that any judge could sentence us to jail on the spot for criminal contempt, but when we said we were ready, he understood and backed off from the threat.

Three judges invited our groups to their chambers for dialogue on our concerns; five engaged in limited dialogue with us in their courtrooms; three ordered U.S. Marshals on duty to remove us from their courtrooms and expel us from the building. All told us it would be legally improper to act on our concerns unless we filed suit by regular process.

I drafted a pro se petition seeking an emergency restraining order and a permanent injunction to prohibit further U.S. military aid to the Contras, and we filed it in District Court, with five named plaintiffs, on July 2.

By that time we had gathered names of 823 petition signers. The case was assigned to Judge Harry Leinenweber, a recent Reagan appointee with a conservative political background. After two appearances on motions, which he denied, we remained standing and displayed books and signs about Contra crimes. He ordered us to leave, and when we refused ordered Marshals to remove us. Nineteen of us were carried or escorted out.

We returned on July 21 on a motion for rehearing, and when he denied it, Kathy and I and nine supporters again refused to leave. The Judge cited us for criminal contempt, ordered the supporters to pay $50 fines, and ordered me, Kathy and John Poole, another plaintiff, to do forty hours of community service, and ordered us all to return on July 25 for a compliance hearing.

At that hearing, when I eloquently explained that Kathy and I had been doing community service for many years, and our current service would be raising these issues in his courtroom, he ordered me and Kathy into custody on civil contempt until such time as we would agree to abide by his orders, offering "the key to the jail".

Taking me in handcuffs to the local Federal Correctional prison, Peter Wilkes, Chief U.S. Marshal for the Northern District, told me, "Karl, that was a beautiful speech that you gave." After five days the Marshals fetched us back before the Judge, who acknowledged that the civil coercion was unlikely to work, and sentenced us to five days for criminal contempt, time served.

His secretary later told us that her phone never stopped ringing with calls from our supporters during the whole five days.

We continued filing motions and briefs in our case, but, after five months, suspended our campaign of nonviolent direct actions, while Kathy and I went back to work to recoup our energies and finances. Leinenweber eventually dismissed our suit.

On three early mornings in March, with a small group of Catholic Workers and allies from Synapses, a Mennonite social justice group, we posted many photos on the plate glass windows of the Federal Court Building. We were arrested quickly, and released within a few hours with citations for defacing Federal property. Janitors stripped the images from the glass.

When Pledge of Resistance leaders realized enforcement would be mild, they copied four hundred "Strip-Tac" posters for our scheduled spring demonstration, and a huge crowd of Pledge supporters circled the Federal Building and posted images on all the first-floor lobby windows. The police did not interfere and no one was arrested. At trial two months later, those of us originally arrested were prepared to argue that we were not defacing the windows, but instead trying to put faces on them, but all of these cases were dropped by the U.S. Attorney.

We then considered putting images on the walls of judges' courtrooms or the fronts of their high benches, but decided on a different tactic. There were twenty-three Federal Judges sitting in Chicago for the Northern District of Illinois.

We wrote a letter and petition to all of them explaining our belief that the Contra attacks against Nicaragua and the U.S. embargo against any trade with Nicaragua were illegal, and we asked them to enjoin the Reagan Administration from continuing them.

We said we would visit their courtrooms to pursue our petition. We delivered copies to all of their offices on March 27, with 166 co-signers listed. Over a three week period we visited the courtrooms of eleven judges, with a number of supporters, at motion call and challenged them to hear our case, starting with Chief Judge Frank McGarr.

He invited me and Kathy to his chambers, where he warned us that any judge could sentence us to jail on the spot for criminal contempt, but when we said we were ready, he understood and backed off from the threat.

Three judges invited our groups to their chambers for dialogue on our concerns; five engaged in limited dialogue with us in their courtrooms; three ordered U.S. Marshals on duty to remove us from their courtrooms and expel us from the building. All told us it would be legally improper to act on our concerns unless we filed suit by regular process.

I drafted a pro se petition seeking an emergency restraining order and a permanent injunction to prohibit further U.S. military aid to the Contras, and we filed it in District Court, with five named plaintiffs, on July 2.

By that time we had gathered names of 823 petition signers. The case was assigned to Judge Harry Leinenweber, a recent Reagan appointee with a conservative political background. After two appearances on motions, which he denied, we remained standing and displayed books and signs about Contra crimes. He ordered us to leave, and when we refused ordered Marshals to remove us. Nineteen of us were carried or escorted out.

We returned on July 21 on a motion for rehearing, and when he denied it, Kathy and I and nine supporters again refused to leave. The Judge cited us for criminal contempt, ordered the supporters to pay $50 fines, and ordered me, Kathy and John Poole, another plaintiff, to do forty hours of community service, and ordered us all to return on July 25 for a compliance hearing.

At that hearing, when I eloquently explained that Kathy and I had been doing community service for many years, and our current service would be raising these issues in his courtroom, he ordered me and Kathy into custody on civil contempt until such time as we would agree to abide by his orders, offering "the key to the jail".

Taking me in handcuffs to the local Federal Correctional prison, Peter Wilkes, Chief U.S. Marshal for the Northern District, told me, "Karl, that was a beautiful speech that you gave." After five days the Marshals fetched us back before the Judge, who acknowledged that the civil coercion was unlikely to work, and sentenced us to five days for criminal contempt, time served.

His secretary later told us that her phone never stopped ringing with calls from our supporters during the whole five days.

We continued filing motions and briefs in our case, but, after five months, suspended our campaign of nonviolent direct actions, while Kathy and I went back to work to recoup our energies and finances. Leinenweber eventually dismissed our suit.

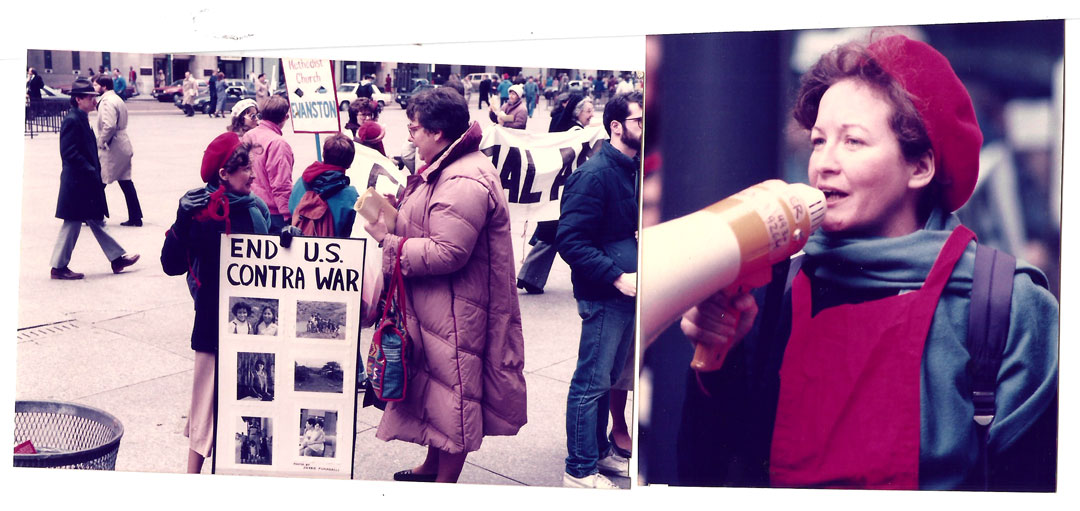

Kathy Kelly doing public educational outreach - Federal Plaza - 3-14-1986

More Nicaragua Solidarity Actions

1986,'87, '88 - At Christmas time in 1986 we Joined with Pledge of Resistance in a mass educational protest action at the eight-story Water Tower Place shopping center on Chicago's Michigan Avenue "Magnificent Mile". We draped banners over the railings of the atrium and sang topically rewritten Christmas carols. Fifty-four people were arrested and charged with trespassing.

At trial, with an effective pro se defense, Kathy and I and some others were acquitted. We made plans to return to Water Tower Place at Christmas Time, 1987. Management found out about our plans, and filed for an emergency restraining order in the local Chancery Court, naming sixty-seven Pledge activists as respondents to the complaint.

Judge Kiley granted a temporary restraining order, but Kathy and I and ten other respondents went ahead with the Water Tower action anyway. The Water Tower Place lawyer went back to the judge and tried to get us punished for contempt. After court hearings, Judge Kiley found that we had violated his orders, but declined to punish us. That didn't satisfy the lawyer, and he appealed Kiley's action to the Appellate Court of Illinois, but, on December 16, 1988, a three-judge panel mildly ridiculed the Water Tower lawyer, declined to second-guess Judge Kiley, and dismissed the appeal.

At all of these trials and hearings, Kathy and I represented ourselves effectively. The reality was that elected Democratic judges in Chicago largely agreed with us about the Reagan neo-imperial policy in Central America, and even when they found us guilty they refused to impose any significant penalties.

In January 1988, while the Water Tower cases wound their way through the courts, Mike Bremer and I undertook another mobile street education project. We rented a small U-Haul stake trailer and built a lightweight plywood cap that could be mounted on it. We prepared visual displays of photographs from Witness for Peace on effects of the Contra War.

After visiting several southside neighborhoods and shopping centers, we went to the Old Orchard Shopping Center in Skokie, which happened to be owned by the same company that owned Water Tower Place. While Mike drove very slowly around the shopping center roadways, Jeff Zacharakis and I began to hand out leaflets and talk to shoppers outside a Marshall Fields store.

Before long we were arrested, and bond for me was set at $3000, which would require posting $300 in cash. I decide to wait in jail for trial, and check out current conditions at Cook County Jail, where I had often spent time in earlier years. My four days there proved very interesting.

That story is told in detail in my autobiography. At trial in Skokie my pro se defense impressed Judge Loverde, and he read the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution to the courtroom audience, before acquitting me, much to the dismay of the prosecutor, Miss Kind.

At trial, with an effective pro se defense, Kathy and I and some others were acquitted. We made plans to return to Water Tower Place at Christmas Time, 1987. Management found out about our plans, and filed for an emergency restraining order in the local Chancery Court, naming sixty-seven Pledge activists as respondents to the complaint.

Judge Kiley granted a temporary restraining order, but Kathy and I and ten other respondents went ahead with the Water Tower action anyway. The Water Tower Place lawyer went back to the judge and tried to get us punished for contempt. After court hearings, Judge Kiley found that we had violated his orders, but declined to punish us. That didn't satisfy the lawyer, and he appealed Kiley's action to the Appellate Court of Illinois, but, on December 16, 1988, a three-judge panel mildly ridiculed the Water Tower lawyer, declined to second-guess Judge Kiley, and dismissed the appeal.

At all of these trials and hearings, Kathy and I represented ourselves effectively. The reality was that elected Democratic judges in Chicago largely agreed with us about the Reagan neo-imperial policy in Central America, and even when they found us guilty they refused to impose any significant penalties.

In January 1988, while the Water Tower cases wound their way through the courts, Mike Bremer and I undertook another mobile street education project. We rented a small U-Haul stake trailer and built a lightweight plywood cap that could be mounted on it. We prepared visual displays of photographs from Witness for Peace on effects of the Contra War.

After visiting several southside neighborhoods and shopping centers, we went to the Old Orchard Shopping Center in Skokie, which happened to be owned by the same company that owned Water Tower Place. While Mike drove very slowly around the shopping center roadways, Jeff Zacharakis and I began to hand out leaflets and talk to shoppers outside a Marshall Fields store.

Before long we were arrested, and bond for me was set at $3000, which would require posting $300 in cash. I decide to wait in jail for trial, and check out current conditions at Cook County Jail, where I had often spent time in earlier years. My four days there proved very interesting.

That story is told in detail in my autobiography. At trial in Skokie my pro se defense impressed Judge Loverde, and he read the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution to the courtroom audience, before acquitting me, much to the dismay of the prosecutor, Miss Kind.

Bill Depenbrock and Karl Meyer with the trailer displays 1-26-1988

In October 1984, as a result of agitation like ours around the U.S., the Congress had passed legislation that prohibited U.S. Government funds from being used to fund the Contras. The Reagan Administration evaded this by soliciting aid from U.S. allies, but in 1985, the Congress prohibited U.S. Government agencies from soliciting other governments for this purpose.

Top officials then concocted an elaborate scheme, that included sale of weapons to Iran, with money from the sale diverted to providing weapons to the Contras. When this "Iran-Contra" scandal was discovered and investigated in the late 80s, fourteen top Administration officials were indicted for related crimes, eleven were convicted, but only one served jail time, and all were eventually pardoned by President George H. W. Bush.

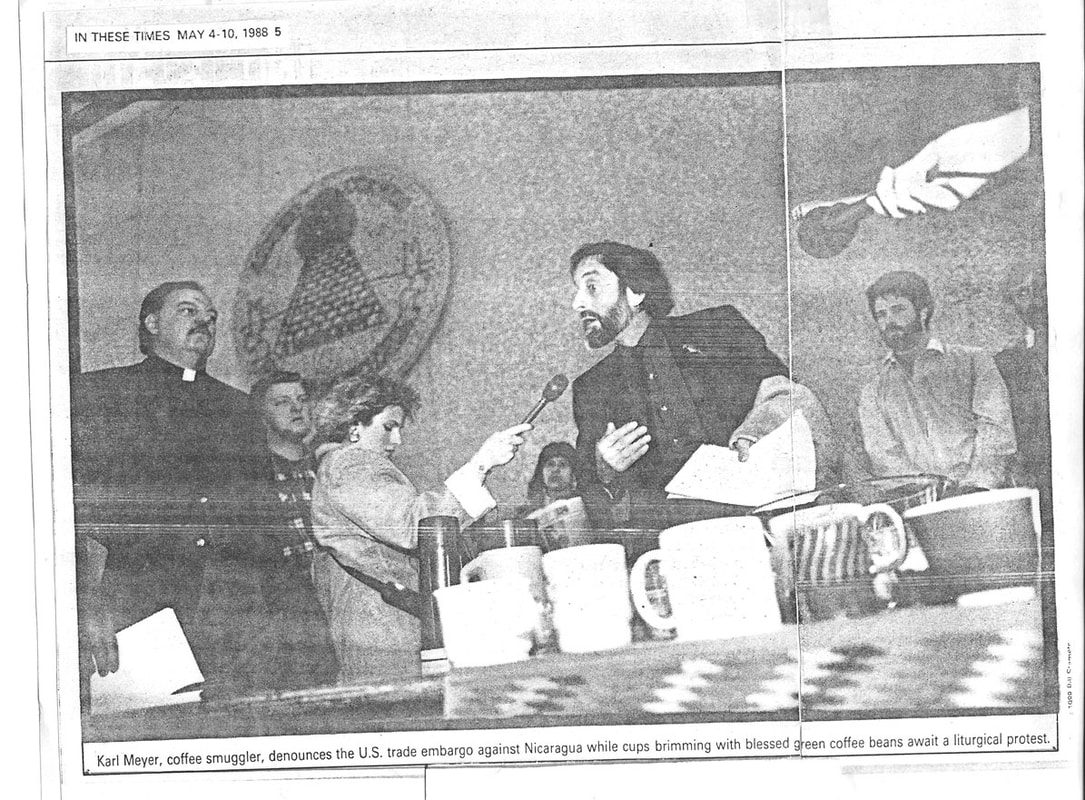

Though military aid to the Contras was curtailed, the Reagan Administration annually certified that Nicaragua posed a threat to the security of the United States, which gave them the power to prohibit all trade with Nicaragua by companies or individuals in the U.S. Our Catholic Worker and draft resistance friends, Leonard Cizewski and Jerry Chernow, in Madison, W I, were importing small amounts of Nicaraguan stamps, art works, and coffee, by way of Canada, and selling them to solidarity activists in the U.S., in violation of the embargo.

We believed that the Administration certifications were fraudulent, and the embargo therefore illegal. On February 13, 1988, Kathy and I drove to Detroit and smuggled a one-hundred, fifty-pound bag of Nicaraguan coffee beans, that Lenny had imported, across the border from Windsor, Canada. We kept forty pounds and the burlap sack marked "Nicaragua Libre" in Chicago, and sent the balance to Lenny in Madison. We had the beans roasted, packaged in one-pound bags and labeled as Nicaraguan coffee.

Then, cooperating with Pledge of Resistance we organized a morning coffee party liturgy and press conference, with prominent local clergy and lawyers, in the lobby of the Federal Court Building, having obtained a permit from a sympathetic Building Manager. We distributed the forty bags of coffee to local ministers and priests for use in educational liturgies or events with their congregations.

Part of our strategy was to provoke prosecution for violation of the embargo in order to raise the issue of the illegality of the embargo in a public trial. Kathy and I had written to U.S. Attorney Anton Valukas and called his office to obtain an appointment.

After the coffee party, five of us went up to his office with a thermos of the coffee and the burlap sack, met with several of his top assistants and had coffee with them, while Kathy and I confessed to smuggling the bag of coffee across the Canadian border in violation of the embargo, a crime carrying a maximum penalty of five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

Valukas didn't take the bait. He later told Sandi Wisenberg, a reporter for the Chicago Reader, "If I were them I wouldn't wait at home to be arrested."

Top officials then concocted an elaborate scheme, that included sale of weapons to Iran, with money from the sale diverted to providing weapons to the Contras. When this "Iran-Contra" scandal was discovered and investigated in the late 80s, fourteen top Administration officials were indicted for related crimes, eleven were convicted, but only one served jail time, and all were eventually pardoned by President George H. W. Bush.

Though military aid to the Contras was curtailed, the Reagan Administration annually certified that Nicaragua posed a threat to the security of the United States, which gave them the power to prohibit all trade with Nicaragua by companies or individuals in the U.S. Our Catholic Worker and draft resistance friends, Leonard Cizewski and Jerry Chernow, in Madison, W I, were importing small amounts of Nicaraguan stamps, art works, and coffee, by way of Canada, and selling them to solidarity activists in the U.S., in violation of the embargo.

We believed that the Administration certifications were fraudulent, and the embargo therefore illegal. On February 13, 1988, Kathy and I drove to Detroit and smuggled a one-hundred, fifty-pound bag of Nicaraguan coffee beans, that Lenny had imported, across the border from Windsor, Canada. We kept forty pounds and the burlap sack marked "Nicaragua Libre" in Chicago, and sent the balance to Lenny in Madison. We had the beans roasted, packaged in one-pound bags and labeled as Nicaraguan coffee.

Then, cooperating with Pledge of Resistance we organized a morning coffee party liturgy and press conference, with prominent local clergy and lawyers, in the lobby of the Federal Court Building, having obtained a permit from a sympathetic Building Manager. We distributed the forty bags of coffee to local ministers and priests for use in educational liturgies or events with their congregations.

Part of our strategy was to provoke prosecution for violation of the embargo in order to raise the issue of the illegality of the embargo in a public trial. Kathy and I had written to U.S. Attorney Anton Valukas and called his office to obtain an appointment.

After the coffee party, five of us went up to his office with a thermos of the coffee and the burlap sack, met with several of his top assistants and had coffee with them, while Kathy and I confessed to smuggling the bag of coffee across the Canadian border in violation of the embargo, a crime carrying a maximum penalty of five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

Valukas didn't take the bait. He later told Sandi Wisenberg, a reporter for the Chicago Reader, "If I were them I wouldn't wait at home to be arrested."

Alderman Dick Simpson, Karl Meyer, Duane Bean - Coffee Liturgy - 4-25-198

Our actions throughout this period gained wide media coverage and public street outreach, and contributed to public debate and opposition to the Reagan policies in Central America.

The civil conflicts in Central America were in part proxy battles in the Cold War confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, because the Soviets supported the Nicaraguan Government and the insurgent rebels in El Salvador and Guatemala.

With the accession of General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union, and the Cold War détente negotiated by Gorbachev and Reagan in the late 80s, the military conflicts in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala were gradually resolved through negotiations leading to participation by the insurgent guerillas in the civil political process in the three countries, but all three countries still suffer from poverty and continuing economic and political effects from years of internal conflict and external interventions.

The civil conflicts in Central America were in part proxy battles in the Cold War confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, because the Soviets supported the Nicaraguan Government and the insurgent rebels in El Salvador and Guatemala.

With the accession of General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union, and the Cold War détente negotiated by Gorbachev and Reagan in the late 80s, the military conflicts in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala were gradually resolved through negotiations leading to participation by the insurgent guerillas in the civil political process in the three countries, but all three countries still suffer from poverty and continuing economic and political effects from years of internal conflict and external interventions.